St. Augustine civil rights heroes Wm. Stetson Kennedy (left) and Dr. Robert S. Hayling, D.D.S. (right) with courageus former State's Attorney Dan Warren (center, in light blue jacket).

Number 2: Add a suitable statue of St. Augustine civil rights heroes, the late Robert S. Hayling, D.D.S. and Wm. Stetson Kennedy, perhaps seated together on a park bench -- as if inviting to sit there, learn from them and commune with their spirits.

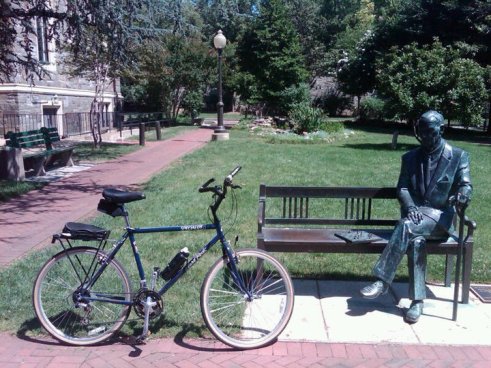

Inspiration: statue of my late heroic Georgetown University "Modern Foreign Governments" Professor Jan Karski, which may be seen on our Georgetown U. campus in Washington, D.C., in New York City, in Israel, and in Kielce, Łódź and Warsaw in Poland. Here's a photo and narrative courtesy of D.C. Bike blogger:

Jan Karski Statue

Posted: April 28, 2014 in Events, Historic Figures, Memorials, StatuesTags: D.C., Georgetown University, Holocaust, Holocaust and Heroism Remembrance Day, Jan Karski, Jan Karski Corner, Jan Kozielewski, Kielce, Nobel Prize, Order of the White Eagle, Poland,Polish resistance movement, Presidential Medal of Freedom, Tel Aviv University, Warsaw, White-Gravenor Hall, Yom HaShoah, Yom HaZikaron laShoah ve-laG'vurah, Łódź

There is a wide variety of different statuary throughout D.C. From Presidents and foreign leaders, to historic figures and other prominent people, most of the statues tend to be very formal in nature, with the subject overtly posed in a manner to invoke power, authority and significance. It is for this reason that I took particular notice of the informal yet distinguished nature of the statue of Jan Karski located next to White-Gravenor Hall on the campus of Georgetown University, at 37th and P Streets in northwest D.C.

Born Jan Kozielewski in Łódź, Poland in 1914, he grew up in a multi-cultural neighbourhood, where the majority of the population was then Jewish. He was raised a Catholic and remained so throughout his life. In 1942 and 1943, Karski was a Polish World War II resistance movement fighter. He became a liaison officer of the Polish underground who infiltrated both the Warsaw Ghetto and a German concentration camp and then, risking death many times, reported the first eyewitness accounts of the Holocaust to the Polish government in exile and the Western Allies.

It seems particularly relevant to be writing today about one of the first and most important people to bring forward information about the Holocaust, because today is Yom HaZikaron laShoah ve-laG’vurah, or Holocaust and Heroism Remembrance Day. Also known colloquially as Yom HaShoah, it is a national memorial holiday in Israel for commemoration for the approximately six million Jews who perished in the Holocaust as a result of the atrocities committed by Nazi Germany, as well as to honor the Jewish resistance during that period.

After the war Karski entered the United States and began his studies at Georgetown University, where he earned a Ph.D in 1952. In 1954, Karski became a naturalized citizen of the U.S. He taught at Georgetown University for 40 years in the areas of East European affairs, comparative government and international affairs, rising to become one of the most celebrated and notable members of its faculty.

He occasionally but infrequently would share his wartime experiences and efforts to warn the world of the Holocaust with students, but Karski said little publicly about his efforts due to the haunting memories of what he had witnessed and thoughts that he had been a failure for not being able to stop it. Decades later, however, he began to speak about it in interviews and documentaries, and as a result returned to public consciousness. He subsequently received long-overdue honors, including honorary citizenship in Israel and Poland’s highest civilian honor, the Order of the White Eagle. He was also nominated for the Nobel Prize and formally recognized by the United Nations General Assembly shortly before his death. And posthumously, he was awarded the U.S.’s highest civilian honor, the Presidential Medal of Freedom. Despite all of the awards and recognition he received, he remained uncomfortable with public attention for the remainder of his life.

In the statue memorializing him, Karski is depicted life size, casually seated on a park bench with his legs crossed and holding a cane in his hands. There is a chess board on the bench next to him with a game in progress. Karski was an avid chess player and was reported to be in the middle of playing a game when he died in 2000. Karski is depicted gazing off to his right, away from the board, as though he were contemplating his next move, or perhaps something more significant.

Other casts of the statue are located in New York City at the corner of 37th Street and Madison Avenue (renamed as Jan Karski Corner), as well as on the campus of Tel Aviv University in Israel, and in Kielce, Łódź and Warsaw in Poland.

No comments:

Post a Comment