FLORIDA RISKS MORE IRMA DEVASTATION BECAUSE GOV. RICK SCOTT DEFUNDED WETLANDS AGENCY

Eoin Higgins

September 9 2017, 7:55 a.m.

AS HURRICANE IRMA, one of the strongest storms ever recorded in the Atlantic, bears down on South Florida, the state is bracing for the worst. “We can rebuild your home, but we cannot rebuild your life,” Republican Gov. Rick Scott said Wednesday. Mandatory evacuations are in place in a number of Florida communities. The state is preparing for extraordinary damage at the hands of the 400-mile-wide hurricane.

Scott, however, took action six years ago that means preparation for the storm must be all the more intense: The Republican governor prioritized development over ecological restoration of wetlands. Scott cut funding for the state’s water management districts in 2011, leading to staff reductions and less funding for ecosystem restoration projects. Around the same time, Scott signed the state legislature’s repeal of the state’s 1985 growth management law, leading to a spike in development. Scott would tell the Palm Beach Post in 2016 that the economic benefits from more building meant Florida was “on a roll.”

As Hurricane Harvey demonstrated in Houston, however, development from depleted wetlands can exacerbate the effects of storms: Water from rain and storm surges will have fewer places to go when the storm makes landfall, creating a greater potential for catastrophic flooding.

“Our wetlands help absorb and hold water,” said Dr. Angelique Bochnak, past president of the South Atlantic Chapter of the Society of Wetland Scientists and a former scientist with the St. Johns River Water Management District in the northeast of Florida. “The more developed the landscape is, the more runoff from rain. And there’s nowhere else to go but flooding without wetlands.”

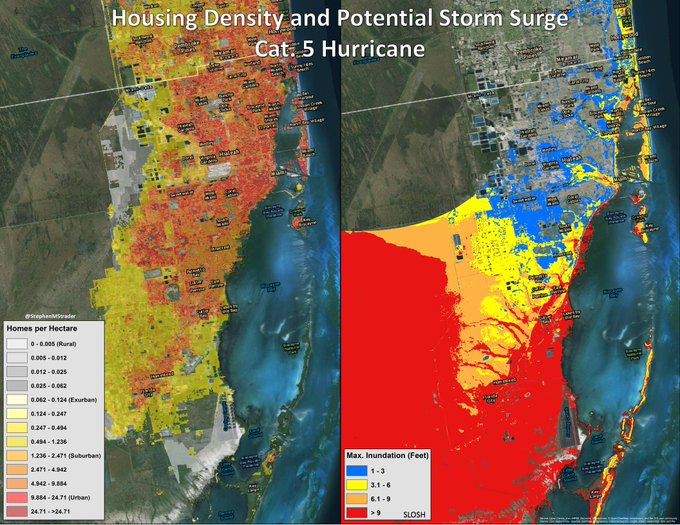

The changes to state priorities around development over wetlands came during a period of few major hurricanes in Florida. During Scott’s time in office, Florida has been spared the ravages of a large and powerful storm. And, in that time, the state has seen an increase in commercial and real estate development that is leaving the southeast coast of the state in danger from Hurricane Irma, which could travel along the coast as a powerful Category 4 storm.

“If it stays on its current forecast track, Irma’s path is about as bad a track as a major hurricane can take through Florida,” said meteorologist Dennis Mersereau. “Instead of hitting the coast head-on and focusing its wind and surge on one spot, the eyewall is forecast to scrape the entire length of the state’s east coast up into Georgia and maybe South Carolina. If that forecast plays out, the extent of flooding from storm surge will be widespread and ugly.”

Irma’s storm surge could reach almost 10 miles inland in Miami on Sunday. Mersereau said that the surge could be as high as 10 feet, though that prediction could and will change as the storm gets closer to the panhandle state. The surge, combined with the rain from the storm, presents a major flooding challenge for Florida.

The governor’s office did not provide comment for this story, instead referring The Intercept to the state’s Department of Environmental Protection, which stressed its commitment to protecting the state’s beaches and shorelines.

“DEP has an entire division dedicated to managing and protecting Florida’s coastal ecosystems,” said department press officer Dee Ann Miller in an email. The department’s Coastal Office, Miller said, cooperates with a variety of allies to maintain the integrity of the state’s coastline. “They work with local stakeholders and federal agencies to implement the statewide coastal management program,” she said, “as well as conduct important coastal research to inform resiliency planning for coastal communities.”

WETLANDS ACT AS NATURAL barriers to the destructiveness of hurricanes. Both coastal and inland wetlands perform different functions to slow the impact of the storms by absorbing storm surge and soaking up rainfall, respectively. A study released this week from Scientific Reports, an online journal from the longstanding environmental publication Nature, spells out the benefits of coastal wetlands in storm mitigation: “Wetlands are estimated to have reduced a little over 1 percent of the flood damage from Hurricane Sandy, though this value varies considerably between zip codes.”

Bochnak said that while the total area of wetlands in the state hasn’t decreased since Scott entered office and defunded the districts, the wetlands have been degraded. That’s because part of the permitting process for development in Florida still involves finding a way to build that does the least damage to wetlands. The districts require any lost wetlands to be replaced elsewhere — but the artificial replacements are generally lower quality wetlands, meaning that the filtration and water storage abilities of the ecosystems are less effective.

“In some areas of Florida, we’ve lost wetlands with the understanding that loss has been mitigated somewhere else nearby,” said Bochnak. “But they’re not necessarily of the same quality.”

A 1996 Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey study found that “no long-term, interdisciplinary research shows unequivocally that a created wetland has fully replaced the lost function resulting from a wetland’s destruction.” Due to the complexity of the lost ecosystems, the study added, their effective replacement was almost impossible.

Until 2011, Florida’s water management districts were run by regulators and scientists and had relatively healthy budgets. But Scott’s order to cut funding for the districts by $700 million, in addition to replacing of district staff with more development-friendly land lawyers and businesspeople, has resulted in a disempowerment of the districts and a less certain commitment to their restorative mission.

A recorded message at the South Florida Water Management District said the organization’s water managers were working around the clock to lower canals and make adjustments for drainage. (The district did not respond to a request for comment.)

Professor William J. Mitsch, the director of the Everglades Wetland Research Park, which works with the district and saw its contract survive the budget cuts, said the governor’s treatment of the water districts has been part of a change to the state institution that made the mission of ecological restoration and water quality a secondary concern to the interests of industry.

“In addition to cutting funding,” said Mitsch, “I saw a change in the agency where they were less working for water quality, wetlands, and nature; and more working for industries. They are serving [industry] more than the people of Florida.”

Mitsch called the funding reductions to wetlands and development-friendly staffing of the agencies a “double whammy.”

With urbanization and commercial and residential development come increased threats from storms like Irma. When Hurricane Harvey hit Houston only two weeks ago in late August, the water had nowhere to go, said Mitsch. “They absolutely paved everything,” Mitsch said of the Texas city, parts of which remain underwater.

Florida has made strides in development over the past years. “Every inch of land we build on takes away a little more of the earth’s ability to handle heavy rainfall, whether it’s through absorption or natural drainage,” said Mersereau, the meteorologist.

Open land in Florida, with its porous terrain, can suck up the energy of the storm. But when passing over developed land, a storm can retain more of its power. Bochnak, the wetlands scientist, said the Everglades could provide necessary water storage but the marshes have been “half-developed into cities and roads,” cutting down on the ecosystem’s potential to lessen the impact of a storm like Irma.

“It’s bad but it’s the hard reality we live in,” said Bochnak. “When we develop these areas, we lose our natural protection.”

Top photo: People put up shutters as they prepare a house for the threat of Hurricane Irma in Miami, Florida, on Sept. 6, 2017.

No comments:

Post a Comment