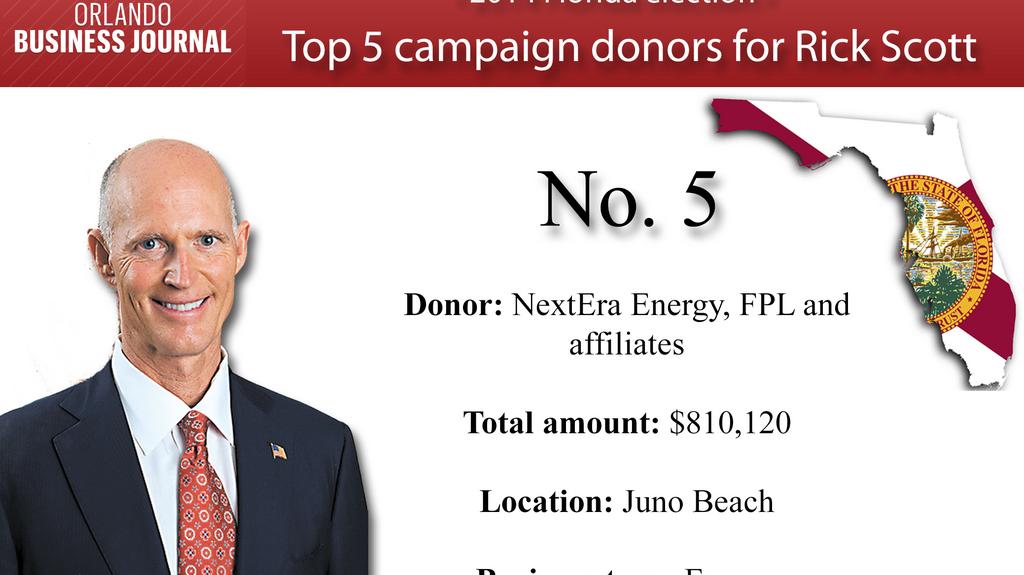

This is the face of corporate homicide -- an investor-owned utility and a Governor who were warned that old people would die in a nursing home, which only needed an easy repair that could have saved lives. It looks like the State's Attorney in Broward County may be faced with a choice of whether to present a grand jury with evidence of manslaughter against FPL and its managers. Fortunately, Florida's pattern jury instructions were changed to reflect Florida law accurately, in 2015, by the Florida Supreme Court, empowering prosecutors to bring manslaughter charges against FPL.

FPL CEO ERIC SILAGY

FPL CEO ERIC SILAGY, Governor RICHARD LYNN SCOTT, with human shields

FPL was warned people would die at a sweltering nursing home. But the utility had other priorities.

Listen to phone calls here.

Florida Power & Light Co. received numerous phone calls urging for the air conditioning to be fixed at The Rehabilitation Center in Hollywood Hills after Hurricane Irma.

By Megan O'Matz

Sun Sentinel

An account supervisor for the power company was concerned by the words of the woman on the phone. The electricity was out at her mother’s nursing home, the temperature felt like 110 degrees and elderly people couldn’t breathe.

The supervisor turned to one of the company’s emergency specialists for advice, saying a caller feared the Hollywood nursing home could have “customers literally passing away because of the heat.”

The co-worker’s response: tell the nursing home to evacuate. “We can’t expedite any outages. So tell ’em to make plans. It’s going to be a long time, to be honest with you … at least a week.”

The next day, on Sept. 13, eight nursing home residents died of the heat. Another four died in later days.

How Florida Power & Light responded to desperate pleas from the Rehabilitation Center at Hollywood Hills after Hurricane Irma is revealed in depositions, audio files, and internal FPL records obtained by the South Florida Sun Sentinel under Florida’s public records law. They include recordings of calls to the utility over the three days the nursing home was without power to its air conditioning.

FPL is one the nation’s largest electric utilities and serves about half of the state. After hurricanes strike, it is a critical lifeline for millions of people and demands on it are extraordinary.

The records reviewed by the Sun Sentinel show FPL workers’ inability to grasp the gravity of the nursing home’s situation, confusion over whether it qualified for “priority” service, and efforts to mollify callers without actually mustering a crew to the scene for what ultimately was a minor repair.

The utility -- which works alongside state and local officials after a storm to address pressing problems -- even failed to respond to an urgent request the evening of Sept. 12 from Broward County’s emergency operations center.

Officials at about 7:30 p.m. appealed to FPL to restore power to the air conditioning at the nursing home and included a hard time frame to get the job done: within two to six hours.

FPL did not comply. About seven and a half hours later, nursing home residents began to die.

Anyone who has ever called a large company for assistance or to register a complaint can relate to the experience of those at the nursing home who tried to convey to FPL the seriousness of the matter and get some extra consideration.

Calls went to customer care center representatives in Miami, West Palm Beach or El Paso, Texas. Those who called numerous times got different FPL agents. Calls were inadvertently dropped and people put on hold. Despite being issued “trouble ticket” numbers, callers had to give the address of the nursing home over and over and continuously restate the nature of the problem.

The customer care representatives dutifully took down the reports, updated notes in the files, and apologized.

“Oh goodness, so sorry!” an operator told James Williams, nursing home engineer, who called Sept. 10, the day the storm hit, to report that the building lost power to the A/C.

He’d explained that it looked like the fuse “just popped out.” He said he could see it hanging on the electric pole outdoors.

The woman entered Williams’ comments into a computer, then appeared to read from a script, saying:

“Unfortunately due to the impact of Hurricane Irma we’re unable to provide an estimate as to when the power will be restored. Currently we have more than 2 million customers out and we have 16,000 workers ready to restore the power. We’re also working with partner utilities, and their workers to restore everyone as quickly and as safely as they can.”

The representative told Williams: “I reported it. I just hope it doesn’t take too much more for you.”

Priority status unclear

FPL spokesman Chris McGrath declined to comment or answer questions from the Sun Sentinel about the utility’s actions or processes in response to Hurricane Irma.

Before hurricane season, FPL and local officials designated which facilities would receive the highest priority for power restoration in each county. In Broward County, they included major hospitals, police and fire stations, 911 centers and other critical sites, but not nursing homes.

Employees and relatives of residents of the Rehabilitation Center at Hollywood Hills believed the nursing home had some priority status as a medical facility – given that it served sick, elderly, bed-ridden people – and was under the same roof as a small psychiatric hospital.

In reporting the outage, Williams urged the FPL representative to “keep in mind that we are a hospital, we’re actually a double hospital: we are a rehabilitation center, and we’re a behavioral hospital.”

Within FPL, there seemed to be confusion over just what that meant.

An FPL agent told Williams that someone at the utility was “personally assigned” to restore power to the nursing home’s chiller account “because we do know it’s a high priority.” The woman put him on hold to get the person’s name and phone number but when she returned Williams had been disconnected. When he called back he got another agent, who didn’t know of any such contact.

In another instance, FPL reassured a caller: “We do recognize it is a nursing home location. It is a priority to us, ma’am.”

Yet when that agent called an emergency specialist about the problem, the agent was told there was no expedited push. “We’ll just let dispatch know, and they’ll work it as soon as they can.”

After a storm, FPL can juggle who gets faster attention, based on the nature of the circumstances.

In a deposition, Gregory Jones, operations lead in FPL’s Gulfstream Service Center covering south Broward County, said the utility gives priority in restoring power to police stations, hospitals, and other facilities, including those that service major customer accounts. The process, he said, consists of “getting the largest number of customers on at any given time, first, then working our way down by customer account.”

Typically, if there is an urgent need, he said, FPL would send the request through to upper management, which would funnel it down to the local service center.

Asked if there was ever a specific request made to him or his operations center to prioritize restoring power at the nursing home, he said: “To my knowledge, no.” If it was deemed a priority, he said, he would have been told.

Records show a service request was sent electronically – in bulk with others -- to the Gulfstream Service Center on Sept. 11, one day after the storm and two days before the deaths.

The “ticket” was labeled Priority 3A, Jones said, meaning the nursing home did not have a full loss of service -- it had electricity for items such as lights, computers and kitchen, but not the air conditioning. And there were no reports of injuries or police or fire calls in the ticket’s “event log,” he said in the deposition.

Asked if someone at the service center noticed the request on a computer screen, Jones indicated that it just sat there while the service workers “dealt with the larger customer accounts and higher priority tickets.”

No comments:

Post a Comment