From Bloomberg BusinessWeek:

Inside the Pro-Trump Effort to Keep Black Voters From the Polls

Breitbart staffer recruited Sanders activist Bruce Carter to get African Americans to support the Republican—or stay home.

Bruce Carter

PHOTOGRAPHER: MELISSA GOLDEN FOR BLOOMBERG BUSINESSWEEK

Breitbart News landed an election scoop that went viral in August 2016: “Exclusive: ‘Black Men for Bernie’ Founder to End Democrat ‘Political Slavery’ of Minority Voters… by Campaigning for Trump.”

If the splashy, counterintuitive story, which circulated on such conservative websites as Truthfeed and Infowars, wasn't exactly fake news, it was carefully orchestrated.

The story’s writer—an employee of the conservative website run by Steve Bannon before he took over Donald Trump’s campaign—spent weeks courting activist Bruce Carter to join Trump’s cause. He approached Carter under the guise of interviewing him. The writer eventually dropped the pretense altogether, signing Carter up for a 10-week blitz aimed at convincing black voters in key states to support the Republican real estate mogul, or simply sit out the election. Trump’s narrow path to victory tightened further if Hillary Clinton could attract a Barack Obama-level turnout.

Bannon’s deployment of the psychological-operations firm Cambridge Analytica in the 2016 campaign drew fresh attention this month, when a former Cambridge employee told a U.S. Senate panel that Bannon tried to use the company to suppress the black vote in key states. Carter’s story shows for the first time how an employee at Bannon’s former news site worked as an off-the-books political operative in the service of a similar goal.

Carter’s recollections and correspondence, which he shared after a falling-out with his fellow Trump supporters, provide a rare look inside the no-holds-barred nature of the Republican’s campaign and how it explored new ways to achieve an age-old political aim: getting the right voters to the polls—and keeping the wrong ones away.

“If you can’t stomach Trump, just don’t vote for the other people and don’t vote at all,” Carter, 47, recalls telling black voters. It’s the message he says the Trump campaign wanted him to deliver. “That’s what they wanted, that’s what they got.”

The work Carter says he did, and the funds he was given to do it, also raise questions as to whether campaign finance laws were broken.

The group Carter founded, Trump for Urban Communities, never disclosed its spending to the Federal Election Commission—a possible violation of election law. In hindsight, Carter says, he believed he was working for the campaign so he wouldn’t have been responsible for reporting the spending.

His descriptions of the operation suggest possible coordination between Trump’s campaign and his nominally independent efforts. If there was coordination, election lawdictates that any contributions to groups such as his must fall within individual limits: no more than $2,700 for a candidate. One supporter far exceeded that cap, giving about $100,000 to Carter’s efforts.

Another potential issue is whether the unusual role played by the Breitbart reporter amounted to an in-kind contribution.

“There are some real problems here,” says Lawrence Noble, who served as general counsel at the FEC during Republican and Democratic administrations and is now senior director and general counsel at the Campaign Legal Center, a nonpartisan advocacy organization. “I would think this is more than enough evidence for the FEC to open an investigation.”

The Trump campaign and the White House didn't respond to repeated requests for comment. Bannon dismissed allegations that he sought to suppress the black vote, blaming their lower turnout on Clinton. “When you ask them why they didn’t vote for her or why they didn’t turn up, it’s because they didn’t like her policies,” he told Bloomberg in an interview last week. Bannon didn't respond to separate requests to explain his involvement with Carter.

Carter’s work on Trump’s behalf ended badly, despite the campaign’s victory in November 2016. A little more than a week after the election, Carter’s financial supporters backed away from plans to work with him on ambitious urban-restoration efforts. In an email, one of them cited a background check on Carter but didn’t specify its findings. Carter acknowledges that he spent 18 months in federal prison nearly two decades ago after a felony gun-possession conviction.

While it’s impossible to precisely measure Carter’s effectiveness, Trump performed particularly well in the areas Carter targeted, says Dustin Stockton, the Breitbart reporter who recruited him. In Philadelphia, where Carter spent much of his time, Clinton won about 35,000 fewer votes than Obama did in 2012, and that drop was primarily in majority-black wards. Those ballots alone could have cut Trump’s victory margin in Pennsylvania by more than half. Nationwide, Trump garnered a higher-than-expected share of black voters, while Clinton won significantly fewer than Obama did four years earlier.

“Trump vastly outperformed the projection models in the 12 areas Bruce was targeting” in Pennsylvania, North Carolina and Florida, Stockton says. “I never like telling people not to vote. But from a tactical and strategic position, we looked at it: If you could get them to vote for Trump, that was a plus two.” It was a “plus one,” he says, if they simply didn’t vote at all.

Carter’s unlikely conversion to cheerleader for Trump started in mid-summer 2016 with a call from Stockton. Broad-chested and 6 feet, 2 inches tall, Carter had become something of a B-list celebrity on the campaign trail, showing up at Sanders’s events in a tour bus emblazoned with the Vermont senator’s photo and yelling through a bullhorn to rally anybody who would listen. He spent months on the road for Sanders, with three of his teenage daughters accompanying him, selling T-shirts and other merchandise to help fund their tour.

Carter says his initial conversations with Stockton seemed more like a chat than an interview. At some point, the Breitbart reporter asked if he had ever considered backing Trump. “I said, I’m not going there,” recalls Carter, a registered Democrat who twice voted for Obama. But Carter had been so angry with how the Clinton campaign and the Democratic National Committee had been treating Sanders that he wasn’t opposed to Trump winning. His anger crystallized when a mention of Carter’s views appeared in the DNC emails released by Wikileaks. So when Stockton asked if they could meet at the Democrats’ national convention in Philadelphia, Carter agreed.

Bruce Carter, founder of Black Men for Bernie, emerges to meet Sanders supporters in front of Los Angeles City Hall in June 2016.

PHOTOGRAPHER: AL SEIB/LOS ANGELES TIMES/GETTY IMAGES

They spent hours at the convention, hanging out. In retrospect, Carter says it felt like a courtship, if at times an aggressive one. Stockton showed Carter a movie called Clinton Cash, which Breitbart was screening in Philadelphia for disaffected Sanders supporters. He discussed Clinton’s shortcomings and the fresh start Trump could offer. “We just kind of struck up a friendship,” says Stockton. “We wanted to make him aware of some of the research that Breitbart was pushing at the time.”

The two chatted regularly after the convention by phone. On Aug. 17, Bannon, then Breitbart’s executive chairman, was named chief of the campaign. The announcement coincided with a push by Stockton to formalize Carter’s role. He says Stockton dangled an intriguing promise—a chance to engage with Bannon. That pushed him over the top: He endorsed Trump.

Stockton and Carter sketched out plans for him to travel to swing states. Carter created a website and launched a GoFundMe campaign that raised about $7,000. On Aug. 26, about 10 weeks before the November 2016 elections, Breitbart published Stockton’s exclusive about Carter.

Not long after, Carter replaced his “Black Men for Bernie” T-shirt with one that sported a black-and-red logo depicting “Trump for Urban Communities,” and he hit the road. Across battleground states, he visited churches, street corners, and storefronts. About that time, Carter says, Stockton introduced him to Bannon.

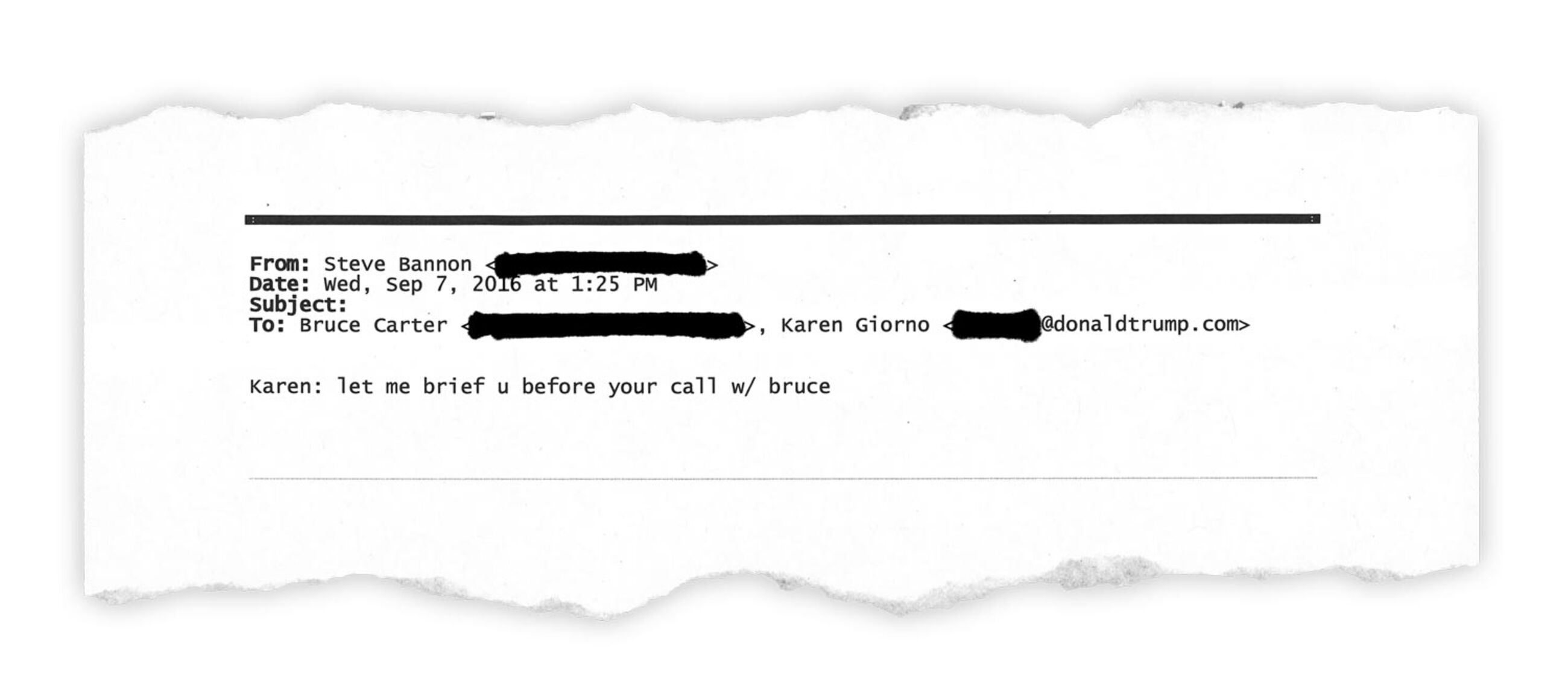

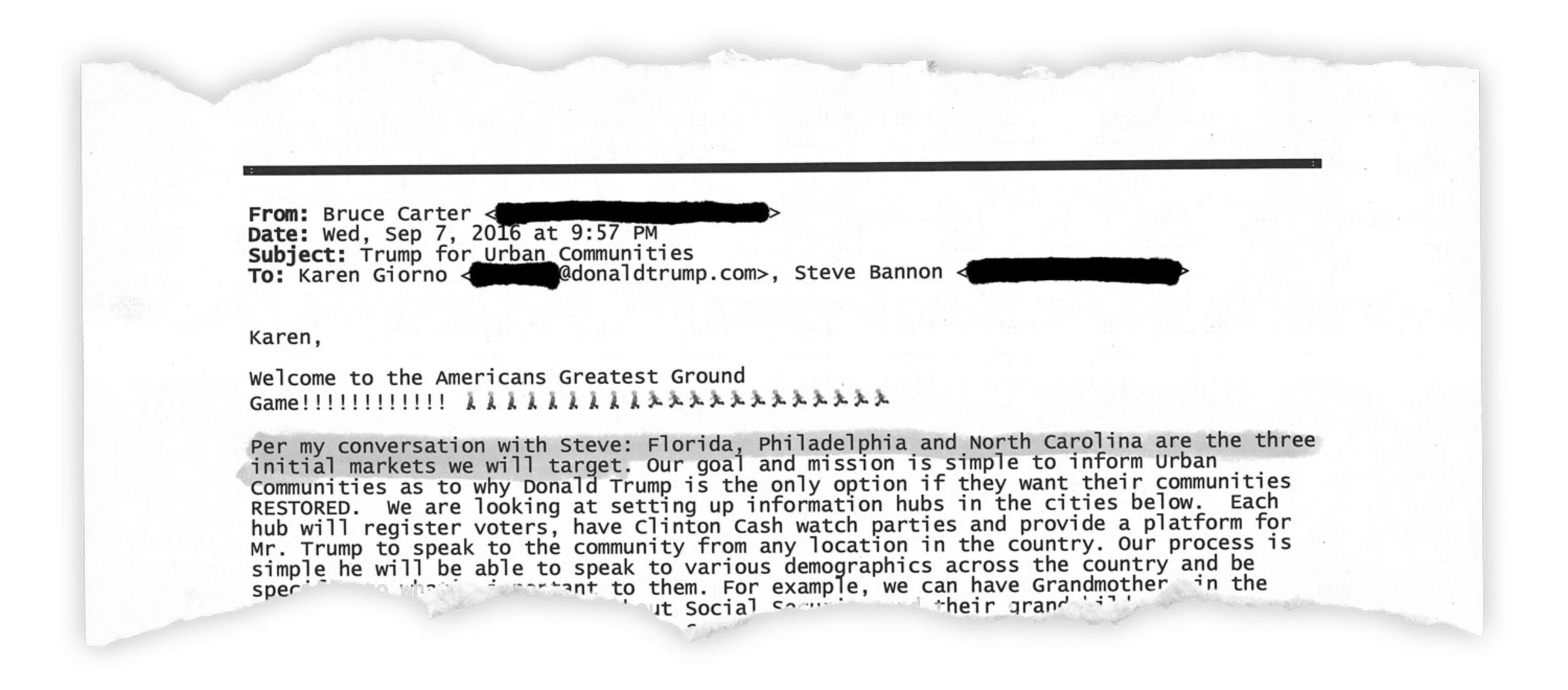

Carter sent an email to Bannon on Sept. 2 seeking money to sustain the effort. He asked that it be funded by “either Trump personally (best case), the RNC, another donor or the Trump campaign,” according to the email. Five days later, Carter received an email from Bannon, introducing Karen Giorno, a senior Trump campaign adviser. Later that day, Carter replied to Bannon and Giorno: “Per my conversation with Steve: ‘Florida, Philadelphia and North Carolina are the three initial markets we will target. Our goal and mission is simple to inform Urban Communities as to why Donald Trump is the only option if they want their communities RESTORED.’”

A Twitter account for Trump for Urban Communities was created on Sept. 11. Carter, who by his own admission doesn’t tweet, enlisted a colleague who did social media for Black Men for Bernie to start tweeting on behalf of his new pro-Trump group. The account originally pushed messages on topics familiar to his former audience, including the Flint water crisis, the Dakota Access Pipeline, and Black Lives Matter. Soon, the account adopted a more Trumpian voice, blasting a steady stream of tweets highlighting the rolling WikiLeaks dumps of stolen Democratic campaign emails and the latest twists in Clinton’s email server scandal, and retweeting such right-wing provocateurs as Mike Cernovich or Infowars.

More people probably had access to the Twitter account than Carter and his Black Men for Bernie colleague. An analysis showed that it was accessed in at least three different geographic locations and by at least two smartphones. A geolocation function on the account was switched off, suggesting that somebody may have been trying to cover their tracks.

Meanwhile, television coverage of Carter during the Democratic convention had drawn the attention of Ceil Pillsbury, a retired accounting professor who lives in Jacksonville, Fla. Watching him, she says, she saw someone who could help her improve the condition of inner cities through the creation of “gang-forgiveness centers” and mentorship programs.

Over time, she became the biggest supporter of Carter’s efforts, providing what she described in interviews as roughly $100,000. In a subsequent emailed statement to Bloomberg News, Pillsbury called into question Carter’s credibility, though she didn’t dispute the amount of support she provided. Pillsbury says she wasn’t aware of any coordination with the campaign and didn’t realize any funds she gave to Carter might have been subject to limits.

Carter says he used the money to help cover the costs of wrapping vehicles in images of Trump and historical black figures, buying T-shirts and other merchandise, and paying for expenses.

Carter’s vans sit parked in front of Trump Tower in New York City on October 28, 2016.

SOURCE: BRUCE CARTER

At each stop, Carter argued that Trump’s business experience would enable him to revive urban neighborhoods in ways Democrats had failed to do. He targeted such places as a barber shop in DeSoto, Tex., a town whose population is 70 percent black.

“So here’s why I’m here,” he begins, according to one video. “Everybody here is voting for Hillary … but let me give you a little history on Hillary. If you understood and saw that Hillary saw young black men as super-predators, would that affect you?” One patron nods his head, acknowledging one of Clinton’s more infamous remarks during her husband’s administration.

The message wasn’t always easy to deliver. People threw rocks at Carter’s Trump van as he steered through low-income housing projects. At one stop in Philadelphia, an elderly man threatened to beat him with a cane. Often, it was impossible to persuade black voters to support a candidate who had strong backing from white nationalist groups. In those cases, he urged them to simply stay home on Election Day.

By early October, Carter says, he needed additional money. With Stockton’s help, he sent a $160,000 funding proposal to Bannon. It included a $24,000 consulting fee for Stockton, which Stockton says was never paid. He has since left Breitbart, where he says colleagues warned him that his work with Carter could be viewed as a conflict of interest. (Breitbart Chief Executive Officer Larry Solov didn’t respond to a request for comment.)

Bannon put Carter in contact with a wealthy Dallas financier, Darren Blanton, who later became an adviser to Trump’s transition team. Blanton is the founder and managing partner of a Texas-based venture capital company called Colt Ventures. Carter said Bannon promised that Blanton would help him raise money.

They met in mid-October at a Starbucks across the street from the Dallas Country Club. Carter says Blanton was sitting with two men when he arrived. One was an Army veteran who ran a Blackwater-like company that provided paramilitary services. The other was Jon Iadonisi, a former Navy SEAL and computer-security expert who has worked for the Central Intelligence Agency.

Blanton told Carter he would help him raise money, while Iadonisi would help spread his message on social media, according to Carter. Iadonisi runs a Texas-based digital marketing company called VizSense that specializes in “military-grade influencer marketing and intelligence services” to promote clients’ products on Instagram and Twitter. He also is a founder of White Canvas Group, a Washington-area firm that specializes in analyzing the dark web. “They were showing me these grids—it just looked like a map of dots,” Carter recalls. “I said, ‘That stuff ain’t going to help you win. You got to get them to the polls.’”

There are indications that both men had dealings with Trump’s campaign. It paid Colt Ventures $200,000 for “data management services,” according to federal disclosures—although Colt Ventures doesn’t advertise data management services. Iadonisi was introduced to the campaign by retired General Michael Flynn, and his work for the campaign involved social media, according to a person familiar with Iadonisi’s role. Democrats on the House Intelligence Committee said in a March report about the panel’s investigation into Russian interference in the 2016 election that they wanted to interview Iadonisi and Blanton, who is an investor in VizSense. The Republican-controlled committee ended its probe without doing so.

For much of the campaign, Carter struggled to get enough money to run his operation. He sent Blanton a string of increasingly frustrated emails and texts complaining that he was having trouble paying his crews. Blanton assured him the funds were coming, according to correspondence Carter provided. In an email, Carter and Blanton’s assistant discussed the logistics of setting up a bank account to receive funds. In response to questions, an attorney for Blanton said in a letter to Bloomberg News that Blanton “did not proceed to set up” the bank account. According to a chain of emails and additional documents Carter provided, Blanton did raise at least some funds for him.

At times, Carter felt that Trump’s team rolled out the star treatment for him. On Oct. 19, the final presidential debate was held in Las Vegas, and Carter made his way to Trump’s luxury hotel, the campaign’s headquarters for the event. Blanton introduced Carter to Flynn and Erik Prince, the Blackwater founder whose sister, Betsy DeVos, would become Trump’s education secretary. At a sandwich shop across the street, Carter says he had lunch with hedge-fund heiress Rebekah Mercer, one of Trump’s most influential backers.

In the final weeks of October, Carter’s operation announced a “Don’t Vote Early” campaign designed to convince black voters not to take advantage of early voting, which tended to build up banks of votes for Democrats. Days before the election, Carter and his team made jabs at Clinton for appearing at rallies alongside stars such as Jay-Z and Beyoncé. “We said Hillary Clinton thinks all black people like rap and like to shake their booties,” he recalls. “It’s an insult.”

As the campaign drew to a close, Carter says, he genuinely believed Trump had big plans for urban neighborhoods. Carter outlined to Blanton in an email a daily strategy for the final days of the campaign. It included the cities he would canvass and an announcement he would make about a Trump-backed public-private partnership that was supposed to raise $1 billion over the administration’s first 24 months to invest in urban communities.

Alexandra Preate, a spokeswoman for Bannon, Breitbart News, and Mercer who runs a New York-based public relations firm called CapitalHQ, circulated a draft press release touting Carter’s efforts. It was sent to Blanton and Iadonisi, among others. The release promised that Trump would create a forgiveness program for non-violent offenders, staff a panel of single mothers to discuss the difficulties of unwanted pregnancies, and establish an Urban Community Commissioner and a Director of Community Justice to investigate police-involved shootings.

On Oct. 26, Trump gave what his campaign billed as a major policy speech in Charlotte. He laid out a “new deal for Black America” grounded in safe communities, better education, and higher-paying jobs.

Shortly after Election Day, Carter’s backers cut ties with him. In an email that Carter provided, Pillsbury cited a background check performed by Blanton that “prevented the campaign and Darren from being able to go any further with you.” Carter says he has never tried to hide his past. He thought it was odd if Blanton did a background check only after the election and Trump had won.

Carter’s work on Trump’s behalf exacted a personal price, leaving deep and lasting divisions in his family. Some of Carter’s children were horrified that their father had backed Trump. In one instance, a month after Pillsbury and Blanton severed their relationship with Carter, an alleged physical altercation over his support for the president-elect led his former girlfriend to obtain a protective order against him.

In early April, Carter got another cold call, this time from somebody who suggested he meet Mark Burns, a black Republican pastor and vocal Trump supporter from South Carolina who’s running to fill a House seat. On April 11, the two appeared together at a news conference in Greenville, where they announced an effort to register 75,000 voters.

Carter is also working on a new political movement that he calls the People’s Ticket—a coalition of single mothers, felons, hospitality workers, and those who owe child support—to “hold accountable” Republicans and Democrats at the polls in 2018 and ensure they deliver on promises for urban communities.

“I did everything that I said I would do,” Carter says, “and I did it in good faith.”

— With assistance by David Kocieniewski, and Stephanie Baker

No comments:

Post a Comment