Tommy Hazouri, a former Jacksonville mayor who turned painful loss into political resurrection, dies at 76

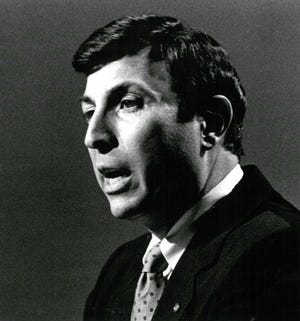

Tommy Hazouri, the prolific Jacksonville politician who pulled off a nearly five-decade electoral streak unrivaled in the city’s modern history — state legislature, mayor, school board, and most recently city council — died Saturday. He was 76.

Hazouri, a loquacious, chip-on-his-shoulder Democrat who sometimes feuded with his own party, once infamously proclaimed himself a staunch opponent of the downtown “fat cats” and never let people forget he used his single term as mayor to rid the city of toll roads and its once-infamous stench from paper mills. Those fat cats sunk his early-'90s re-election campaign, but they could never lock him out of political power. He continued to win elections for decades.

Hazouri had been hospitalized at Mayo Clinic last month for complications stemming from a lung transplant he underwent last year. He was recently released back to his Mandarin home into hospice care.

Earlier:Jacksonville Councilman Tommy Hazouri hospitalized for lung transplant complications

More: Tributes pour in for former Jacksonville Mayor Tommy Hazouri

The family announced his death Saturday.

"He spent his final days at peace surrounded by his family and friends; and in typical Tommy fashion, there was no shortage of laughing, reminiscing and holding loved ones close," his family said in a statement. "In times of intense fury, overwhelming sorrow or unpredictable turmoil, he always insisted people put differences aside and come together. This optimism was especially important to him in recent years."

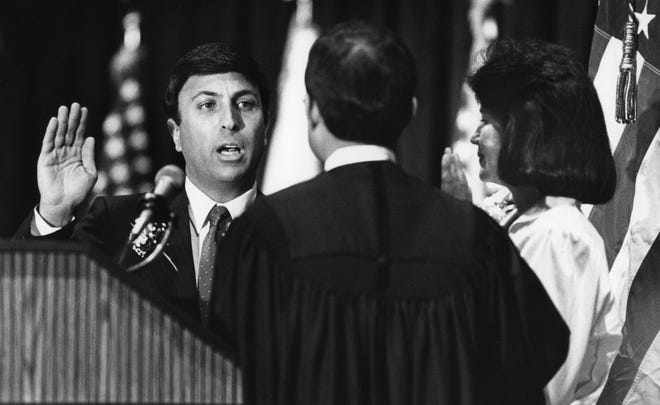

Hazouri was born in Jacksonville and attended Andrew Jackson High School and Jacksonville University, where he got his first taste of politics in student government. Sent to the Florida House of Representatives the year President Richard Nixon resigned from office in 1974 and by age 46 running successfully for mayor, Hazouri’s remarkable longevity in public life saw multiple setbacks and comebacks, and ultimately lasted until his final days this summer.

"Our city mourns the loss of a true Jacksonville champion," Mayor Lenny Curry said Saturday. "Tommy, I will always value your friendship, leadership and passion for our community. You will be dearly missed."

Hazouri savored the give-and-take of politics, and his refusal to fade away from that arena was his defining characteristic.

City Council member Matt Carlucci said when Hazouri lost his re-election bid for mayor, he answered a television reporter’s question about what was next for him by reciting the nursery rhyme “The Itsy Bitsy Spider” about rain washing down the spider until the sun came back out.plug into the stories that define it.

“I love to tell that story,” Carclucci said. “Tommy didn’t give up. That’s the moral of the story. The itsy-bitsy spider never gave up, and Tommy never gave up.”

Hazouri was the first Arab-American mayor in city history, a product of the large diaspora of Lebanese and Syrian families who settled in Jacksonville more than a century ago and became a cornerstone of the city’s character.

But Hazouri, running for mayor in 1987, still faced down prejudice. His opponent that year, John Lewis, told The Times-Union that Hazouri could not be elected because of his ethnicity, and the once politically influential First Baptist Church in downtown sent letters to congregants calling Lewis the “real Christian” in the race.

Hazouri, displaying a flair for acerbic one-liners that would later define his political style, responded by dubbing his opponent “John the Baptist."

Memorable wins and losses

During his term as mayor, Hazouri won voter support for a half-cent sales tax for the Jacksonville Transportation Authority that resulted in the elimination of tolls from several bridges and roads, and he led the push for new local laws that cut industrial odor pollution, shedding Jacksonville’s reputation as the “city that stinks.”

Those fights and others, including controversies over finding a site for a new landfill and a surprise $96 garbage-collection fee included in one of his budgets, depleted his political capital, as did his combative public persona.

Hazouri came to believe the downtown “fat cats” had it in for his little-guy agenda, and they in fact did: Civic and business leaders recruited the state attorney, Ed Austin, to run against him, ultimately ending an era of Democratic Party dominance in city politics.

Narrowly losing re-election to Austin was a slight that seemed to permanently wound Hazouri — he remained sensitive about any mention of it in newsprint even decades later — and he was never able to return to that pinnacle of municipal power. But it did not deter him from public life. If he couldn’t be mayor, Hazouri could still win citywide races further down the ballot with wide margins, based on the strength of his name alone.

"Tommy's view was you could have both clean air and the jobs. That also of course was not popular," said former Jacksonville Mayor John Delaney, who ran against Hazouri in the mid-'90s.

"I've been quoted as saying 'Tommy wasn't a big man but he was a muscular politician,'" Delaney said. "He was not afraid to fight a fight if he thought he was right. He didn't care who he made mad, even friends ... if he really felt on an issue that this was the right thing for the public, then bam, that was the right way he would go."

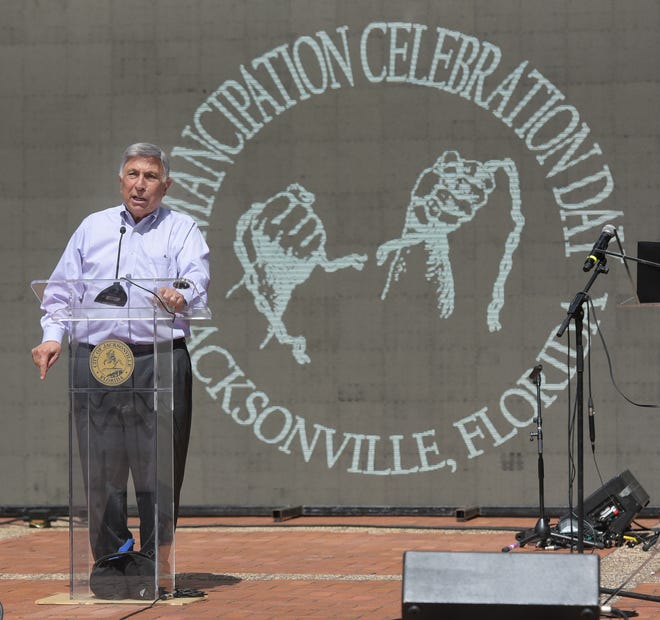

His declining physical health seemed to hasten a new urgency into his time on the City Council. Following his lung-transplant surgery in July 2020, Hazouri said he was inspired to lead the city into an “era of enlightenment” during his council presidency.

Carlucci said Hazouri’s term as City Council president was the perfect capstone to his legacy.

“Tommy, as City Council president, was in the right place at the right time with the right voice,” Carlucci said.

Hazouri formed a special committee on racial justice and policing and backed a doubling of the local gas tax proposed by Curry. It was an instrumental piece of a plan to more rapidly complete a long list of transit projects, connect historically neglected neighborhoods to city water and sewer lines and free up money for more spending on parks, libraries and other public services.

Hazouri, whose life spanned the pre- and post-consolidation eras in Jacksonville's government, viewed the gas tax as a critical component to fulfill decades-old promises of renewed infrastructure to the city's oldest neighborhoods.

His sometimes-tumultuous term as the council president also set him at odds with Jaguars owner Shad Khan over a high-profile development deal and saw him lead vocal opposition to holding the eventually canceled Republican National Convention in Jacksonville last summer.

'Great instincts for people and the public'

City Council member Brenda Priestly-Jackson, who also served with Hazouri on the Duval County School Board, has said she nicknamed him “Hazardous,” as an inside joke about the “good trouble we make serving together.”

Hazouri sometimes struggled to keep pace with the changing politics within his own party, which occasionally alienated him from the base. In 2008 while serving on the Duval County School Board, he voted against removing the name of Confederate general and KKK leader Nathan B. Forrest from a local high school. But later in life, as a member of the City Council, he became a leading advocate behind the successful push to expand the city’s human-rights ordinance to outlaw discrimination against gay, lesbian and transgender people.

Hazouri relished political fights, was reliably quotable — he’d quip that legislation he didn’t like was a “pig in a poke” — and soaked up media coverage. Sometimes his exuberance led him into pickles: Making an inappropriate comment to a colleague or jumbling his words behind the council dais.

Opponents frequently mistook his verbal stumbling — he could sometimes speak in near-stream of consciousness — to mean he’d lost a step, but Hazouri never shed his essential canniness: He knew better than almost anyone how to win and which issues to birddog for a political advantage.

"Tommy just had great instincts for people and the public," Delaney said. "He had kind of a sixth sense for that."

Always, Hazouri’s emotions ran just beneath the surface: He could exude intense personal warmth or bluntly inform a political opponent — or reporter — he’d been deeply offended by a slight.

He nurtured friendships and grudges just the same, and often, as with much in his life, he worked through those relationships publicly. Sometimes that led to farce: Years ago in one notable feud, Hazouri called a former Jacksonville state legislator the “queen of mean” after she said she wanted to pull the toupee off his head.

Hazouri had a remarkably roller-coaster relationship with the current mayor, Curry, as well. They traded insults shortly after each had been elected to office in 2015 — Curry, a Republican, perplexed the septuagenarian by quoting Jay-Z lyrics to slight him — but they later made up so completely they endorsed one another's re-elections four years later, which infuriated local Democrats.

They then fell out again — "the mayor is full of it," Hazouri said amid a fight earlier this year over a development deal backed by the mayor. And then they made up one last time over Curry's gas-tax proposal this summer.

But no relationship was more emblematic of this dynamic than his on-again-off-again blood feud with his predecessor, former Mayor Jake Godbold, who died last year.

The two back-to-back Democratic mayors once had a radioactive falling out that bled from political into personal. One theory of its origin was rooted in Hazouri’s decision to oust key Godbold aides shortly after he took office in 1987.

Regardless of its provenance, the feud was long-lasting and self-destructive: In 1995, with both men plotting their political comebacks in City Hall with rival mayoral campaigns, they only managed to sabotage each other. Hazouri, after losing in the primary, backed the Republican, John Delaney, over Godbold, who narrowly lost.

They patched it up before the end and had become more a buddy-cop duo than sworn enemies. Hazouri sometimes joked he never expected to outlive Godbold, whom he quipped would endure through the apocalypse.

"I didn't really do any major initiative without talking to Jake [Godbold] or Tommy," Delaney, the former mayor, said. "It's just hard to believe that somebody with that much life energy has been taken from us now."

Hazouri is survived by his wife, Carol, and one son, Tommy Jr. Funeral arrangements have not been announced.

Times-Union writer Teresa Stepzinski contributed to this report.

nmonroe@jacksonville.com

dbauerlein@jacksonville.com

No comments:

Post a Comment