In 1974, just six years out of law school, William Sheppard was appointed to represent Duval County inmates in a federal case over living conditions at the jail.

The legal battle over those issues, including overcrowding, ultimately led to the construction of a jail that opened in 1991.

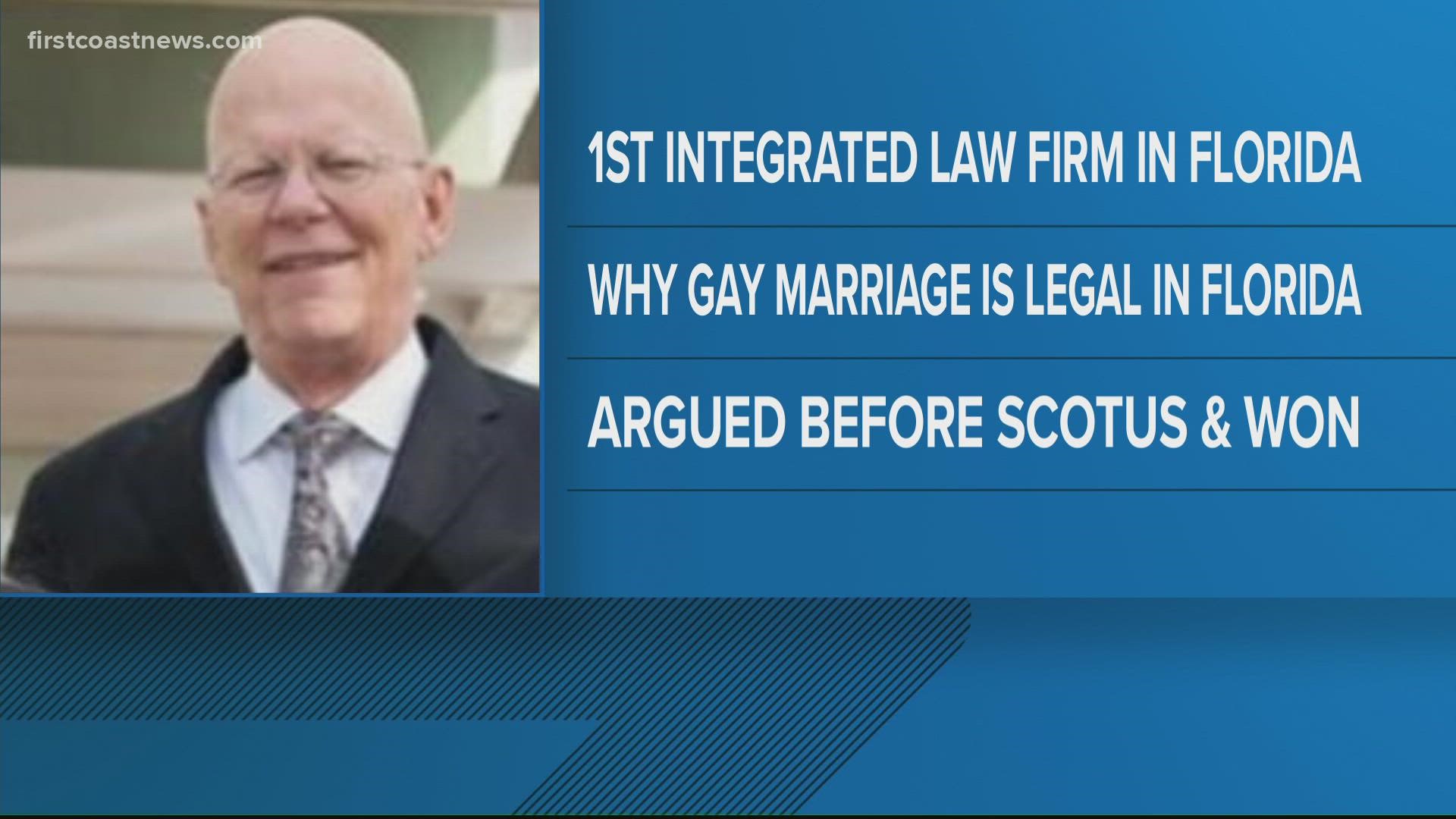

It was an early victory in Sheppard’s path to building a law practice rooted in civil rights work, though many others followed, including the 2015 marriage equality case in Florida.

Now, as he nears his 50th year in practice, the firm has another federal civil rights case involving the jail. This time, the fight is about how bail practices impact misdemeanor offenders who can’t afford to pay. They either plead guilty even if they’re not or “languish” in jail, the lawsuit said.

Florida Department of Corrections records show Duval County detains, by far, more pretrial misdemeanor defendants than any other county in the state.

The lawsuit, with three misdemeanor offenders as the plaintiffs, was filed Aug. 30 against 4th Judicial Circuit Chief Judge Mark Mahon and Jacksonville Sheriff Mike Williams. It contends the bail system violates the equal protection and due process clauses of the U.S. and Florida constitutions.

Sheppard and Elizabeth White, his wife and law partner, talked last week about why they filed the suit over the long-standing policy now; some of the resourceful techniques they used to gather the information, including putting people in first appearance court to help gather statistics; and why civil rights cases are important to the firm. Here is an edited version of the discussion:1

The bail bond procedure has been in place for a long time. Why did you decide to challenge it now?

Sheppard: Well, I think it’s like everything else, its time has come. There’s a nationwide movement going on and we’re kind of at the lead of it. Not the lead, but not too far behind the lead pack. It’s happening across the country and it’s going to accelerate. And it’s going to skyrocket to the U.S. Supreme Court, I predict in about two years.

I think the issue of why, too, is we are beginning to realize that just the sheer numbers are not sustainable. The number of people who are being locked up for misdemeanors that really don’t belong there is costing the system so much money.

White: Millions of dollars. When you think about where the money could be going in terms of prevention, or even providing education programs and mental health programs within the jail, it’s just money that needs to be spent elsewhere.

Sheppard: I have been trying to do this since 1974 ... when I recognized the jail was overcrowded. How do you un-crowd an overcrowded facility? You let people out. Who do you let out? The ones least likely to be hurtful to anybody. That would be nonviolent misdemeanants.

White: This even becomes an issue when you talk about the facility itself. You think about a house that was supposed to be built for a family of four and family of eight is living in it. That’s when you start getting plumbing issues and you’re seeing a lot of the plumbing issues. The plumbing in that facility was not designed for the number of people using it.

Is the process driven by money for some people?

Sheppard: If you drove around Jacksonville five years ago, I wonder how many bail bonding companies you would have found. I remember when I started there were about two. Now there are probably 200. Where does that money go?

There’s about five major national insurance companies that all this money funnels to. It is big, big corporate America and they make millions of contributions to lobbyists every year to keep this in place.

In all of these cases around the country where people are bringing these suits on behalf of the inmates, inevitably the bail bondsmen intervene in the cases.

Talk about the process you went through to investigate the issue. It must have taken an amazing amount of research, interviews and reviewing public records. And it had to be expensive.

Sheppard: Because I’ve spent so much of my life litigating over jails and prisons, I’m tuned in to what’s going on.

And I talk convict talk. I represent a lot of people who are in and out of the jail. I have lawyers that I work with that are in and out of the jail.

About a year ago I picked up on movement in this area.I followed all of the cases that are traveling through the court system.

White: Then you tried to put a court reporter in J-1 (court) and she got thrown out.

Sheppard: Yeah, they weren’t welcome.

White: We were trying to get our court reporter in there just for the information to avoid the considerable expense that would be incurred by having to order official transcripts. ...We were not going to use it as an official transcript. (The request was denied by Mahon, White said.)

Sheppard: I devised another method to get the numbers, so I got them several different ways. I sat people in the courtroom.

White: We literally put people in the courtroom. For a long time. Over six months.

Sheppard: I talked to a jillion people in and out of the system. And obtained (public) records. It took a lot of legal research to feel confident that I’m on solid ground, too.

How did you piece it all together?

White: We were comparing, OK, what do we see here? What is this agency saying here? Then we also actually interviewed inmates in the jail.

That becomes a little tricky because they get worried, “I’m going to talk to these lawyers and the next thing I’m going to get in trouble or they’re going to add more charges.”

We tried to be protective so that people didn’t feel like they would be in jeopardy if they gave us information.

Can you talk about the impact on a person who is held for so long because they can’t afford bail?

Sheppard: You lose your job, you lose your family, you lose your money. They’re on the street because they lost their job because they couldn’t make bail.

White: It could be my age, but I see how it affects the mothers. You see these women in their 60s there every weekend to see their sons. They may have grandchildren and may be taking care of them.

One person never goes to jail. It’s the family. There’s a real lack of looking at the big picture of who gets affected.

You cannot discount the mental health factor of this. It’s not like this is somebody that says, “Oh, I’ve graduated from college and I know what I need to do X, Y and Z.” They don’t have anybody to help them understand the process to begin with.

That’s why they end up at the jail. There’s no place for them. Yes, there are nonprofits here that are doing their very best. It’s not enough. It’s just not enough.

Why are these types of cases so important to you?

Sheppard: Mine’s kind of hokey. When I went in the Army, I took an oath to uphold the Constitution and I was willing to kill you for it. When I became a lawyer, I took the same oath. I’m not going to kill you, but I’m going to make you live by the Constitution if I have the power to do it.

White: I became a civil rights lawyer because my dad was in the Air Force and saw the death camps after they were liberated and he saw Japan after it was bombed. I have very clear memories of him telling me the measure of a society is how we treat the least fortunate.

We feel like we have a duty to uphold the Constitution. This guy (Sheppard) keeps free copies of the Constitution in his waiting room and has done it long before anyone else.

The bottom line is we are talking about human beings and they are not being treated in a humane way. I think at a minimum that we have the right to expect that from the system. I really do.

From his Sheppard, White, Kachergus & DiMaggio law firm webpage biography:

Email

sheplaw@sheppardwhite.comSheppard, William “Bill” J.

William J. Sheppard, a board certified criminal trial lawyer, has established a reputation as a preeminent criminal defense, civil rights and appellate attorney during his nearly 50 years practicing law by committing both himself and his practice to his clients’ cases. Both icon and iconoclast, Mr. Sheppard is known for representing the famous, the infamous, and the unknown alike. Throughout his career, he has fought at every level of the judicial system for individuals’ protections against violations of their rights, whether by searches, internet or other electronic surveillance, restrictions on freedoms of speech and religion, or violations of the constitutional rights of the incarcerated and accused. He has litigated virtually every type of criminal case, from death penalty cases to complex white collar defense.

Mr. Sheppard prepares meticulously for any task at hand. He understands that only the most extensive preparation will result in effective representation of his clients. In order to be thorough, Mr. Sheppard also makes sure that he knows and understands his clients, as well as the circumstances that have resulted in their need for legal representation. Whether a case must be fought in the courtroom or resolved through negotiation, Mr. Sheppard brings nothing short of the most thorough preparation, skill and diligence for the protection of his clients’ interests.

After serving as a First Lieutenant in the United States Army in Korea, Mr. Sheppard graduated from the University of Florida College of Law, where he served as Executive Editor of the Florida Law Review. Mr. Sheppard began his legal career in the fields of real estate and banking, before founding his own firm, which he dedicated to the pursuit of criminal defense and civil rights advocacy.

Mr. Sheppard has litigated Florida’s landmark statewide jail and prison conditions case on behalf of inmates in the county, municipal jails and state prisons in the State of Florida, producing substantial improvements to the provision of adequate care for those in custody. He has also established himself as a distinguished criminal defense lawyer, having litigated countless constitutional issues on behalf of his criminally accused clients. From issues relating to the Fourth Amendment to questions litigated under the Fourteenth Amendment, Mr. Sheppard’s knowledge of the law is encyclopedic. To witness Mr. Sheppard’s impact on the law, one needs to look no further than his nearly 400 published opinions.

His pursuit of the vindication of his clients’ rights has resulted in his having argued before the United States Supreme Court on three different occasions, including in Doggett v. United States, 505 U.S. 647 (1992), which established that a delay between indictment and arrest can violate the constitutional right to a speedy trial. Because of such accomplishments, Mr. Sheppard has been recognized by his peers through such accolades as his long-standing AV Preeminent Martindale-Hubbell rating and his listing in Best Lawyers in America in the fields of appellate law, first amendment law, labor and employment law, non-white-collar criminal defense law, and white-collar criminal defense law, and through his listing in Florida Super Lawyers. Additionally, he was awarded the Lawyer of the Year in White-Collar Criminal Defense, Non-White Collar Criminal Defense and Employment Law in 2010, 2012, and 2014 respectively. Only a single lawyer in each practice area is honored as “Lawyer of the Year,” and it is the rare lawyer who has garnered these awards in three separate areas. Further, he is a Master of the Bench Emeritus in the Chester Bedell Inn of Court and a Fellow in the American College of Trial Lawyers.

His accomplishments have been further recognized by his appointments to membership on the Florida Governor’s Advisory Committee on Corrections, the Middle District of Florida Civil Justice Reform Act Commission, and a term as chair for the Judicial Nominating Commission for the Fourth Judicial Circuit of Florida. Additionally, Mr. Sheppard has been recognized by his receipt of several awards including the Nelson Poynter Civil Liberties Award from the American Civil Liberties Union on two occasions.

He has received the Florida Bar Foundation Medal of Honor, which is the highest honor bestowed upon a lawyer by the legal profession in Florida, the Tobias Simon Pro Bono Award, which is given annually by the Chief Justice of the Florida Supreme Court to the attorney in Florida who has given the most outstanding pro bono service, the Selig I. Goldin Memorial Award, which is presented annually by the Criminal Law Section of the Florida Bar for making significant contribution to the criminal justice system of the State of Florida, and the Steven M. Goldstein Criminal Justice Award, the highest honor awarded by the Florida Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers.

Mr. Sheppard has also received the Distinguished Service award presented by the National Federation of the Blind, the Civil and Human Rights award from the International Association of Official Human Rights Agencies, the Mary L. Singleton Justice, Peace and Social Harmony Memorial Award, and the Florida Bar President’s Pro Bono Service Award. Recently, he was the recipient of the First Coast Coalition’s Humanitarian Award, which recognized Mr. Sheppard’s support and ingenuity to the civil rights involvement.

In 2015, Mr. Sheppard received the Henry Lee Adams, Jr. Diversity Trailblazer Award presented by the Jacksonville Bar Association Diversity Committee. This award is given to those who show outstanding leadership for diversity and inclusion efforts. Mr. Sheppard is very proud to have received this award, named after one of his former law partners.

Mr. Sheppard has litigated cases throughout the country and is admitted to the Florida Bar, U.S. District Courts for the Middle, Southern and Northern Districts of Florida, U.S. Supreme Court, U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth and Eleventh Circuits, U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit, U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, and U.S. Tax Court.

He was recently featured prominently in the book Fifty Years of Justice: A History of the U.S. District Court for the Middle District of Florida by James M. Dunham, published on June 9, 2015 by the University Press of Florida.

Practice Areas

- Criminal Defense

- White Collar Crime

- Civil Rights

- Professional Licensure

- Post Conviction Relief

- Criminal Trial Practice

- Criminal Appeals

- Employment

- Sealing and Expungement

Education

- University of Florida College of Law, Gainesville, Florida

- Florida State University

Bar Admissions

- Florida, 1968

- U.S. District Court Middle District of Florida

- U.S. District Court Northern District of Florida

- U.S. District Court Southern District of Florida

- U.S. Supreme Court

- U.S. Court of Appeals 4th Circuit

- U.S. Court of Appeals 5th Circuit

- U.S. Court of Appeals 7th Circuit

- U.S. Court of Appeals 11th Circuit

- U.S. Court of Appeals Federal Circuit

- U.S. Tax Court

Honors

- Humanitarian Award presented by the First Coast Coalition, 2009

- The Florida Bar Foundation Medal of Honor Award, 2004

- Steven M. Goldstein Criminal Justice Award, 2001

- Nelson Poynter Civil Liberties Award presented by the ACLU, 2000

- Selig Goldin Memorial Award, 1993

- Civil & Human Rights Award, 1990

- Tobias Simon Pro Bono Award presented by the President of the Florida Bar, 1985

- Nelson Poynter Civil Liberties Award presented by the ACLU, 1982

- National Federation of the Blind of Florida Distinguished Service Award, 1978

- Florida Legal Elite

- Super Lawyer

- Martindale Hubbell (AV) - 30 Years

- Best Lawyers in America, 2010

- Best Lawyers in America, 2012

- Best Lawyers in America, 2014

- Best Lawyers in America, 2018

- Best Lawyers in America, 2019

- Henry Lee Adams, Jr. Diversity Trailblazer Award, Jacksonville Bar Association Diversity Committee

- Robert J. Beckham Equal Justice Award presented by Jacksonville Area Legal Aid, 2016

Certified Legal Specialties

- Board Certified Criminal Trial Lawyer, Florida Bar

Professional Associations

- National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers

- Jacksonville Bar Association

- The National Trial Lawyers

- Florida Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers

- The American College of Trial Lawyers

- Chester Bedell Inn of Court, Master Emeritus

No comments:

Post a Comment