After a mosquito bite in 1943, my father contracted malaria in Sicily as an 82nd Airborne Division paratrooper, silently suffering the lifetime effects.

Now, in 2022, I'm running for a seat on the board of our Anastasia Mosquito Control District of St. Johns County (AMCD), and would be honored to have your vote on or before November 8, 2022.

Our Florida way of life and our tourist economy rest on controlling the disease-carrying pestiferous mosquitoes that once made this place virtually uninhabitable.

Thanks to Commissioner Jeanne Moeller, AMCD is now a leader, not a punchline for cool Ed Hall cartoons. Chairman Moeller's leadership, and Commissioner John Sundeman's, helped halt wasteful spending. The battles were epic, Sunshine laws were violated and exposed, and the public interest finally prevailed over illegal, no-bid purchase of a $1.8 million luxury Bell Jet helicopter. I was proud to be a part of it, joining with Robin Nadeau, former Army Captain Don Girven and other local residents in asking questions and demanding answers. AMCD was saved from an unwise proposed St. Johns County takeover, and remains today as an independent scientific and technical organization that is becoming known as a world leader on environmentally-friendly mosquito control.

Thanks to the will of the people of St. Johns County, informed by good reporting by local journalists, AMCD now practices and teaches safe, sane mosquito control, saving lives from mosquito-borne diseases.

While malaria is not a current threat here, other mosquito-borne diseases are, and could increase with global climate change.

From the American Association for the Advancement of Science's SCIENCE Magazine, current issue:

Lingering feverIN SECTION FEATURE

Moisés Mapanga, a burly man of 49, is the bait. At 6 p.m. on a mid-April evening, he climbs into an orange tent outside his one-room house in Matutuíne, a hot, swampy district near Maputo, the capital of Mozambique. He will remain there for the next 12 hours, except for a 30-minute dinner and bathroom break.

Mosquitoes hunting for their next blood meal fly into the tent, where they are attracted not only to Mapanga, who sleeps under a second tent to protect him from their bites, but to a red light atop a lantern-shaped mosquito trap. Instead of dining, the insects are sucked into a collection cup by a battery-powered fan. The next night Mapanga will repeat the drill with the tent inside his house.

Junior entomologist Mara Máquina of the Manhiça Health Research Centre (CISM) and her colleagues are on site to inspect the catch. They are testing house after house in Matutuíne to figure out which species of malaria-carrying Anopheles mosquitoes occur there and whether they are biting indoors or outside. The answers might help reduce the disease’s horrendous toll in Mozambique.

But the project also aims to help answer a bigger question: Why, after Mozambique and its international partners have spent years pouring money and energy into fighting malaria, have cases plateaued, and in some places increased? “We do almost everything we can to decrease the burden, but we are not seeing the impact we would expect,” says Pedro Aide, malaria area coordinator at CISM.

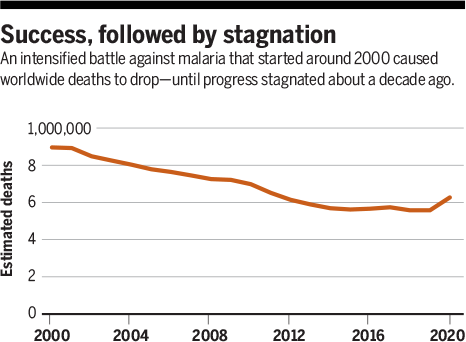

The pattern is similar in many countries in southern Africa. After more than a decade of striking successes against the disease, cases are now bumping along a generally flat line, slightly up one year, down the next, with no real progress. Researchers hope Mozambique, which has the fourth-largest malaria burden in the world, can shed light on what is happening across the region.

The question bothers donors as well. Last year, the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuber-culosis and Malaria, which in late 2020 gave Mozambique $200 million for 2.5 years to control malaria, requested an analysis to figure out why it is not seeing a greater payoff. Unfortunately, “There’s not one obvious answer,” says James Colborn, a senior malaria adviser at the Clinton Health Access Initiative who led the analysis.

Part of the problem is that “the mosquitoes are fighting back,” Aide says. Tried-and-true interventions against malaria, such as bed nets treated with long-lasting insecticide and spraying the indoor walls of houses with insecticides, are losing power because mosquitoes are changing their behavior and resistance to the chemicals has become rampant. The vagaries of human behavior factor in as well, as does poverty, with which malaria is intertwined, and a lack of health services. And a warmer, wetter climate, on top of the cyclones and flooding that pound the country almost every year, is creating even better conditions for mosquitoes to flourish.

Whatever the causes, it’s clear that fixing the problem will require new tools—especially in central and northern Mozambique, where malaria still kills tens of thousands of children each year.

GLOBAL SPENDING on malaria control and elimination started to go up sharply after the turn of the century, thanks mostly to the launch of the Global Fund in 2002 and the U.S. President’s Malaria Initiative (PMI) in 2005. Malaria spending surpassed $3 billion annually by 2010 and has plateaued since then. As spending elsewhere began to drop, however, support for Africa, which has by far the world’s worst malaria problem, continued to rise. It passed $2.5 billion in 2020.

The results were stunning—at least initially. Between 2005 and 2015, the number of estimated yearly cases globally fell by 30% and the mortality rate dropped by 47%. But then progress ground to a halt at what the World Health Organization (WHO) calls “unacceptably high” levels. There were an estimated 241 million cases and 627,000 deaths in 2020, mostly in children in Africa.

The paradox is acute in Mozambique, whose entire population of 31 million is at risk. PMI has so far spent more than $415 million to fight malaria in the country and the Global Fund $530 million. Yet, countrywide incidence jumped from 226 cases per 1000 residents per year in 2015 to 368 per 1000 in 2020, an increase of more than 60%, according to PMI. More than 11 million cases were diagnosed in 2020, about 90% of them caused by Plasmodium falciparum, the most dangerous of the four malaria parasite species. Another measure of malaria intensity is prevalence, the percentage of children under age 5 who have malaria parasites in their blood, regardless of whether they are sick. In Mozambique, that number hasn’t budged from about 40% nationwide since 2011.

One encouraging sign is that the number of deaths has been declining gradually in Mozambique, thanks to better access to rapid diagnostic tests and the best drugs, artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs). But the country still saw an estimated 23,700 deaths in 2020, according to PMI. Malaria is a leading cause of death among young children.

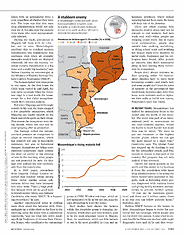

The toll is not evenly distributed. Mozambique stretches 2500 kilometers along the Indian Ocean, and malaria transmission varies dramatically with climate and topography. It’s highest—and has increased sharply—in the country’s center and the north, with their humid tropical climates. Transmission is much lower, and has decreased, in the drier lowlands of the south. The stark difference is reflected in the prevalence rates in children under age 5, which range from 57% in Cabo Delgado, a province in the far north, to 1.3% in Maputo, the country’s southernmost province (see map, p. 1141).

Poverty exacerbates malaria—and Mozambique is one of the world’s poorest countries. The underprivileged live in flimsy housing that offers little protection from mosquitoes, and they are the least likely to receive care. Even when malaria does not kill, the disease perpetuates poverty because the sick cannot work or go to school.

MAPUTO PROVINCE is Mozambique’s malaria success story—but even there, efforts have fallen short of their goal. In the 1990s the government began to fight malaria in earnest, in large part to assuage its neighbors, South Africa and Eswatini, formerly Swaziland. Those countries wanted to wipe out malaria altogether and were frustrated that migrant workers and others from Mozambique kept bringing it back in. “They look to us and say, ‘Hey, you guys need to fix your problem there,’” says Abuchahama Saifodine, the U.S. Agency for International Development’s Maputo-based resident adviser. The Mozambican government also hoped getting rid of malaria would foster development and tourism.

The south has been a testing ground for new techniques ever since. In 2015, with funding from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the La Caixa Foundation, the government and its partners, CISM and the Barcelona Institute for Global Health, embarked on a bold, 2-year pilot to test the feasibility of eliminating malaria in Magude, one of Maputo’s seven districts.

They threw everything they had at the problem. All residents received insecticide-treated bed nets. Pregnant women, who are at risk of severe disease and anemia, were offered prophylactic antimalarials when they sought antenatal care. In addition, every house received indoor spraying once a year to drive down the mosquito population. The project also tried something new for Mozambique: providing the district’s entire population with an antimalarial twice a year, regardless of whether they were sick. The hope was that this mass drug administration would not only cure the ill, but also clear the parasite from those who were asymptomatically infected.

During the study, prevalence in Magude fell from 9.1% to 1.4%—but not to zero. Malariologists attribute this to residual malaria transmission—the transmission that continues even when all available mosquito control tools are deployed effectively. All over the country, “residual malaria transmission is a big issue and a really big headache,” says Nelson Cuamba, an entomologist at the Ministry of Health’s National Malaria Control Programme (NMCP).

The human-baited tent traps point to one cause. At the first house the CISM team visited in mid-April, the trap came up empty when the volunteer slept in a tent inside the house, except for a few Culex mosquitoes, which don’t transmit malaria.

But when Mapanga spent the night outside in his tent, the traps snagged a few Anopheles mosquitoes, which Máquina can readily identify by the black-and-white spots on their wings. That means the mosquitoes were biting outside, where bed nets and indoor spraying offer no protection.

The findings reflect the intense, constant pressure on mosquitoes to adapt to control measures, which has resulted not only in insecticide resistance, but also in behavioral changes. Mosquitoes are biting more outdoors—sometimes right outside the door—or earlier in the evening or later in the morning, when people are not protected by nets. Or they may feed indoors but rest outdoors, safe from the insecticides.

In a 2019 paper, researchers from Imperial College London reported that outdoor biting among three vector species across sub-Saharan Africa may have increased 10% since 2000. That’s a huge problem because there are no good tools to thwart outside biters, says Baltazar Candrinho, who heads NMCP. “It is happening everywhere,” he says.

Another experimental setup is yielding more clues about the behavior shift. Entomologists lay a white sheet on the floor in the morning, spray the house with a commercial insecticide, “and see what falls down dead,” says Krijn Paaijmans of Arizona State University, Tempe, who coordinates the entomology group at CISM. Window exit traps, which allow mosquitoes to fly in but not out, snag the ones attempting to leave the house.

Such studies have shown the balance within the Anopheles genus is changing. An. funestus, which bites and rests indoors, used to be the most abundant vector in Maputo. Now, An. arabiensis, which can bite indoors or out, is the most plentiful. In Gaza and Inhambane provinces, where indoor spraying has not been used, the team still finds lots of An. funestus.

There are other reasons why mosquito control alone may not be enough to end malaria. Bed nets work very well—when people are sleeping under them. But in many rural communities, people stay outside late, cooking, socializing, or doing school work and avoiding hot houses made even steamier by metal roofs, Paaijmans and his colleagues have found. After people go indoors, they don’t necessarily jump in bed, leaving them vulnerable to mosquitoes.

People don’t always welcome indoor spraying, either. It’s inconvenient—families have to move their belongings outside—and smells bad, and some people don’t trust the army of sprayers or the government that sends them, Saifodine says. After they leave, some residents wash or replaster their walls or build new rooms, Paaijmans’s team has found.

IN RECENT YEARS, Mozambique has shifted its antimalaria focus to the center and the north of the country. The move was part of an international push to concentrate on the high-intensity regions, where the battle is much harder but more lives can be saved. “We want to put our resources in the highest burden places where we can get the most impact in a short time,” Candrinho says. The Global Fund has stepped up its funding to pay for the intensified attack, and PMI spends its money in this part of the country. But progress has not only stalled; it has reversed.

There’s too much malaria in the north and the center to try to chase it from the population with mass drug administration or by using the finely honed tools deployed in Magude, such as following every person diagnosed with malaria home and giving family members antimalarials to prevent further spread. “If you are in Zambezia [province] and there are 2 million cases, there is no way you can follow patients home,” Saifodine says.

Rather, NMCP focuses on the basics. In 2016, Mozambique began to strive for universal bed net coverage, which means one net for every two people. It also tried to ensure health facilities are stocked with rapid diagnostic tests and ACTs and that every-one who shows up with a fever is tested for malaria and treated. Also, all pregnant women who seek antenatal care are offered chemoprevention.

So why did cases continue to surge? The study Colborn and colleagues just finished for the Global Fund mentioned several possible reasons. One somewhat hopeful explanation is that Mozambique has gotten better at detecting and testing cases, Colborn says, which could explain part of the frustrating statistics. But Colborn’s analysis listed many other potential factors. Insecticide resistance in mosquitoes may be worse than researchers realize. The shifts in mosquito behavior that Paaijmans’s team is documenting may be having a profound impact across the country. “If we were able to measure all potential factors affecting transmission, we would probably have a good idea of why we see stagnation or an increase in malaria,” Colborn says. At this stage, “we can say: This is what we don’t know and what we need to know.”

There are also stubborn realities in this vast, very poor country. “Universal coverage is not universal,” Candrinho concedes. The most recent national data, from 2018, showed just 69% of the population had access to a bed net, despite campaigns to distribute 16 million to 17 million nets across the country every 2.5 years, about the life span of a net. Across central and northern Mozambique, there are often no community health workers. People have to walk 2 to 3 hours to get to a health facility, and many don’t. Many women don’t seek antenatal care.

Once they do get to a clinic, a number of things can go wrong. Health workers don’t always ask whether the patient has a fever; of those with fever, only some are tested for malaria, and of those, only some receive ACTs, a recent study by Candrinho, Colborn, and colleagues found.

A big part of the problem in central and northern Mozambique is that malaria is so common people tend to shrug it off. Some people don’t know malaria is transmitted by mosquitoes or how to protect themselves.

That’s why on a hot spring day a religious leader in Nampula province, Juma Alberto Munlela, is talking about malaria with a group of about 15 men in a straight row of plastic chairs under the span of a huge tree. They live in Namaita, a devastatingly poor community far off a paved road in Rapale district.

Munlela is with the Inter-Religious Program against Malaria (PIRCOM). Funded by PMI, it employs respected religious leaders of all faiths—Muslims, Christians, Hindus, and Baha’i—to educate people about malaria, and is spreading its message in five of Mozambique’s 11 provinces.

Munlela begins with a prayer before asking whether anyone knows where malaria comes from. Mosquitoes, a man volunteers, and they like standing water, so it is important to clean your house. Malaria gives you fever, headaches, and convulsions, another adds. Malaria is deadly, Munlela explains, and children and women are especially vulnerable. If anyone has a fever, go to a health facility right away and get tested for malaria. Take the antimalarial for the full 3 days even if you feel better—if you take it just 2 days malaria is not over. “God wants you to go to the hospital,” he intones.

Next, Munlela stresses the importance of sleeping under a bed net, and his PIRCOM colleagues demonstrate how to assemble a bright blue one. A young man follows their example, climbs in, and laughingly mimes sleep. But there’s a problem, another man says: The community has no bed nets.

PIRCOM staff will return to Namaita in a few weeks to see whether the community is following their leader’s advice, for instance by seeking care when they feel ill. “Changing behavior is not something you say today and it happens tomorrow,” says Herminio Rafael Guitutela, PIRCOM’s provincial coordinator in Nampula. “It’s a process.”

AS RESEARCHERS SEARCH for answers to Mozambique’s malaria puzzle, one thing is abundantly clear: New strategies and tools are needed if the country is to bring down its sky-high burden.

To thwart insecticide resistance, NMCP is rolling out next-generation bed nets, which use a combination of two insecticides or another formulation, in four provinces. Colborn thinks that is one reason cases dipped in those provinces last year. “It is the first obvious success I have seen from one intervention.” Next-generation nets will be distributed to the rest of the country over about the next 6 months, he says.

Last year NMCP, supported by the Global Fund, tried mass drug administration in an entirely different context—not for malaria elimination in the south, but to reduce disease and death in Cabo Delgado, the northernmost province, where conflict has displaced hundreds of thousands of people and caused malaria to spike. The drugs were given in two areas where most of the displaced are concentrated. Data are still being analyzed, but the strategy helped, Aide says: “Malaria transmission continued, but we didn’t see the expected increase in cases after the peak malaria season.” NMCP may try the approach in other high-burden provinces as well.

The nonprofit Malaria Consortium, in collaboration with NMCP and CISM, is conducting a 2-year pilot study of a brand-new strategy for Mozambique: seasonal malaria chemoprevention, which involves giving all eligible children ages 3 months to 59 months intermittent doses of a powerful antimalarial drug combination—|sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine and amodiaquine (SPAQ)—during the high-transmission season.

Seasonal chemoprevention is widely used in the Sahel, where it’s been shown to reduce malaria incidence by 75%. But it has never been tried in sub-Saharan Africa, for a couple of reasons. Malaria is highly seasonal in the Sahel, Aide says—it is either on or off—so it is very clear when children are most vulnerable. In Mozambique, malaria is seasonal as well, but the incidence never drops to zero. Also, resistance to sul-fadoxine-pyrimethamine among malaria parasites is high in Mozambique, which could blunt SPAQ’s effectiveness.

But the malaria burden remains so stubbornly high that in 2020 NMCP decided to give the strategy a try in two districts in Nampula province. The first phase, last year, showed seasonal chemoprevention is safe, feasible, and widely accepted, says Maria Rodrigues, Mozambique country director of Malaria Consortium. Now, the collaborators are testing its effectiveness.

In one of the districts, remote and dusty Malema, local women recruited for the study were going door to door in April, talking to mothers and distributing SPAQ. Community leaders had already paved the way, explaining that the strategy is prevention, not treatment, and helping dispel any rumors.

At the first house, a 2-year-old girl with huge brown eyes, perched on her father’s hip, is feverish and subdued. Because she is sick, she can’t take SPAQ, Rodrigues explains. Instead, the team urges the father to take her to the health center immediately to be tested for malaria.

At other houses, the community distributors show mothers how to dissolve the tablet, making an orange-flavored liquid that most children like. For those too young to drink from a cup, mothers make a paste and spoon it into the child’s mouth. When the distributors are done, they mark the door with chalk, recording the date, how many children received the drug, and whether they need to come back to catch any they missed. Several days later they will return and collect a card that the mother has filled out showing how many doses she delivered.

So far, the Malaria Consortium has treated about 114,000 children. Preliminary data are very encouraging, Rodrigues says: A comparison with two control districts suggests seasonal chemoprevention reduced malaria incidence about 85%. This year, NMCP will expand the strategy across all of Nampula province, targeting 1.3 million children.

Mozambique is also one of two countries, with Tanzania, testing a novel use of ivermectin, a drug used to fight parasites in people and animals that also kills mosquitoes feeding on people who have taken it. In the study, led by the Barcelona Institute for Global Health, researchers are giving ivermectin to both humans and their livestock, which mosquitoes also feed on, in mass campaigns for two consecutive years. Used in combination with other tools, “it could be a great innovation,” Saifodine says.

Yet another tool may be coming. Mozambique was one of the early trial sites for RTSS, the first-ever malaria vaccine, which WHO approved last year for widespread use in areas of moderate to high malaria transmission. The vaccine is in short supply and far from perfect, with an efficacy of just 30%. But if you consider the number of people at risk in Mozambique, it could make a big difference, Candrinho says. NMCP and its partners are considering how it might be used in combination with other tools and whether to apply for funding.

Like other innovations, the vaccine costs money, which, despite the influx of external funding, is scarce in Mozambique. None is a panacea. But Saifodine remains optimistic that, working with the tools they have and trying to figure out where each makes sense, Mozambique can finally start to make progress. “If we can find a solution for funding, a lot of great things can happen,” he says.

No comments:

Post a Comment