June 6, 1944, Sainte-Mère-Église, Normandy, Nazi-occupied France

My Father was a proud anti-fascist.

So am I.

So are the people of the United States of America.

My Father was part of the 82nd Airborne 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment (P.I.R.), which jumped out of C-47 airplanes and "parachuted in"+ with our United States Army paratroopers around 1 AM: those who survived swiftly took over the first Nazi-occupied European town before the sun even rose that day. +

Fun fact: Walt Bogdanich, heroic three-time Pulitzer Prize winning New York Times reporter, spent 59 days in St. Johns County during 2013, investigating the murder of Ms. Michelle O'Connell in the home of St. Johns County Deputy Jeremy Banks. ButKATHY NELSON, then an ignorant newly appointged St. Augustine Record "Editor and Director of Audience," accused three-time Pulitzer Prize winner Walt Bogdanich of "parachuting in," asking him if he had any "regrets." Long part of the Establishment, so often propagandizing for Sheriff DAVID SHOAR f/k/a "HOAR," the fetid St. Augustine Record was part of the coverup, never covering the murder until the PBS Frontline and New York Times stories appeared, serving as a willing accomplice to SHOAR's propaganda.

Dad was one of 11,000 American paratroopers; he was a non-commissioned officer (non-com) with our 82nd ABN DIVN, 505th PIR, F Company.

Dad landed on a roof at a French farmhouse. The farmer offered him refuge, thinking dad was a pilot who had been shot down. Dad thanked the farmer, but declined, saying "No, I have to go fight" the Nazis.

The Southern New Jersey Chapter of the 82nd ABN DIVN ASSN is named for my dad, the "CPL EDWARD A. SLAVIN Chapter."

I sometimes wear dad's "CPL EDWARD A. SLAVIN Chapter" jacket to events, including occasions when our City of St. Augustine is violating human and civil rights.

In his spirit, we band of brothers and sisters in St. Augustine have repeatedly defeated the forces of oppression more than 75 times since 2005.

In his spirit, we wear oppressors' scorn as a badge of honor.

Reemember the words of the "weather prayer, written by a Roman Catholic priest for Third Army General George S. Patton, Jr. before the Battle of Bastogne: "Graciously hearken to us as soldiers who call upon Thee that, armed with Thy power, we may advance from victory to victory, and crush the oppression and wickedness of our enemies and establish Thy justice among men and nations."

Another website states: "The paratroopers jumped prior to the actual start of the invasion "H-Hour". Because of the tradition of being the first into the fight, the 505th Regimental motto is "H-MINUS". For their performance in the invasions the 505th was awarded the Presidential unit citation, the unit equivalent of the Medal of Honor awarded to individual soldiers. In the words of author Clay Blair, the paratroopers emerged from Normandy with the reputation of being a pack of jackals; the toughest, most resourceful and bloodthirsty in Europe."

Freedom is not free.

The U.S. Capitol 1/6 insurrection taught us that freedom must be zealously guarded by all of us. My dad taught me, as JFK's dad taught him, that you have to stand up to people with power or they walk all over you. As the German immigrant, Civil War General and later Wisconsin's Republican U.S. Senator Carl Schurz so eloquently said, "My country, right or wrong; if right, to be kept right; and if wrong, to be set right.”

On D-Day, I'm fondly remembering my late father, Edward Adelbert Slavin, Sr., a WWII 82nd Airborne Division paratrooper, sole surviving son of Polish-American immigrants who fled Russian oppression and pogroms.

Dad volunteered for military service the day after Pearl Harbor was sneak attacked by Japan. (The Navy would 't take him because he was color-blind. So he volunteered to be one of the new paratroopers in the 82nd Airborne Division.)

One Memorial Day, my dad bought American flags for every row house on our block in Pennsauken, N.J., just before we moved to a ten acre former farm in Mantua. The Cathoic Star-Herald ran an evocative photo of my dad holding me up as we adjusted one of the American flags he bought for Norwood Avenue. I learned from the caption or "cutline" of that ancient newspaper photograph that my dad was a machine-gunner with the 82nd. He never told me that.

With the 82nd, my dad jumped into Nazi-occupied territory on two continents, in North Africa, Sicily (where dad caught malaria) and Normandy (where dad was wounded).

My dad recovered from his knee wound in U.S. Army hospitals, including one in Amarillo, Texas. Dad later taught map-reading to soldiers at Fort Benning (where he and my mom were married after VJ-Day).

My dad was sometimes called "the old man" by his much younger 82nd Airborne comrades. He was the "morale non-com."

Research confirms that my dad was one of the oldest men in the 82nd, at nearly 32, when he and the 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment helped liberate Sainte-Mère-Église, the very first French town taken back from Nazi tyranny, before dawn on June 6, 1944.

The South Jersey Chapter of the 82d ABN DIVN. ASSN., INC. is named in his honor, the "Edward A. Slavin Chapter." He served on the 82nd ABN DIVN ASSN. Board of Directors for years,

Dad did a lot to find 82nd veterans and enlist them in chapters and conventions. Dad and I researched newspapers using the Editor and Publisher yearbook we borrowed from the Woodbury Public Library, sending press releases around the Nation. Dad was grateful when many fellow former soldiers would read articles in their local newspapers (in North Dakota, or wherever). Inspired, they attended conventions, joined nascent chapters, and relived their experiences with former comrades, at a time when Americans had not yet come to grips with PTSD among our veterans,

As a Georgetown University student, I was proud to receive an 82nd ABN DIVN ASSN, INC. scholarship to help pay for my tuition and expenses.(A few years before, during the Vietnam War, my dad proudly stated that I was "anti-war" on national television, in an interview by Joe Garragiola with three 82nd veterans during their annual convention, on NBC's Today Show circa 1970 during the Vietnam War. It appeared Mr. Garragiola was trying to bait combat vets into condemning anti-war protesters. My dad calmly replied, "My son is anti-war," ending Garragiola's divisive line of attack.)

Col. Benjamin Hayes Vandervoort was portrayed by John Wayne in the movie, The Longest Day.

* Footnote: My dad won three Bronze Stars, a fact he also did not tell me, and which I did not learn about, until Memorial Day weekend of 1998, when I saw a program on local television interviewing three veterans of three wars, while I was visiting at home during the recess of a nuclear powerplant whistleblower trial in Camden, N.J., where I was born,

Benjamin Hayes "Vandy" Vandervoort (March 3, 1917 − November 22, 1990) was an officer of the United States Army, who fought with distinction in World War II. He was twice awarded the Distinguished Service Cross. He was portrayed by John Wayne in the 1962 war film The Longest Day.

Vandervoort transferred to the newly established paratroopers in the summer of 1940, and was promoted to first lieutenant on 10 October 1941. Promoted to captain on 3 August 1942, almost eight months after the American entry into World War II, he served as a company commander in the 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment (PIR), commanded by Colonel James M. Gavin. He was promoted to major on 28 April 1943,[2] a few weeks after the 505th had been assigned to the 82nd Airborne Division, then commanded by Major General Matthew Ridgway, and served as operations officer (S-3) in Colonel Reuben Tucker's 504th Parachute Regimental Combat Team in the Allied invasion of Sicily and in the landings at Salerno.

Promoted to lieutenant colonel on 1 June 1944, he was the commanding officer of the 2nd Battalion, 505th PIR, during the American airborne landings in Normandy. Vandervoort led his battalion in defending the town of Sainte-Mère-Église on 6 June in "Mission Boston", despite having broken his ankle on landing. During "Operation Market Garden" in September 1944, he led the assault on the Waal Bridge at Nijmegen while the 3rd Battalion, 504th PIR, made the assault crossing. Ridgway described Vandervoort as "one of the bravest and toughest battle commanders I ever knew".At Goronne he was wounded by mortar fire, so was unable to take part in the 82nd Airborne Divisions' advance into Germany in 1945.

He was promoted to colonel on 7 July 1946, and left the Army on 31 August. After studying at Ohio State University he joined the Foreign Service in 1947. He served as an executive officer in the Department of the Army in 1950-54, acting as joint political adviser to the commanding general United Nations forces and UN ambassador, Korea, in 1951-52, and studied at the Armed Forces Staff College (now the Joint Forces Staff College) in 1953. He served as a military attaché at the US embassy in Lisbon, Portugal, in 1955-58, and was assigned to the Department of State in 1958-60. He then served in the Executive Office of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), from 1960–66, also serving as a consultant on politico-military affairs to the US Army Staff in 1960, and as a plans and program officer on the Army Staff, Department of Defense, in 1964.

Benjamin Vandervoort died on November 18, 1990 at the age of 73 years at a nursing home from the effects of a fall. He had two children with his wife Nedra; a son (Benjamin Hayes Vandervoort II) and a daughter (Marlin Vandervoort).

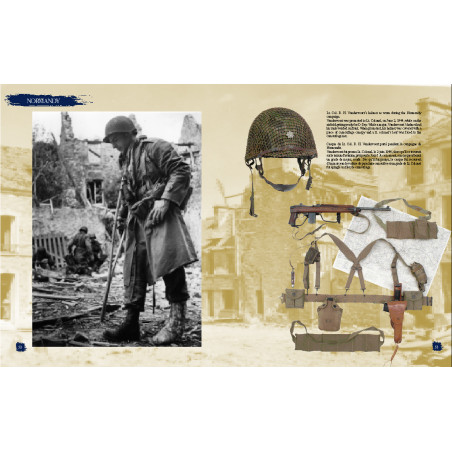

Photo courtesy Michel Detrez

D-Day Experience, Saint Côme du Mont

---------------

Sainte-Mere-Eglise: The 82nd Airborne Drops into France

In Normandy on the night of June 5/6, 1944, the U.S. 82nd Airborne Division overcame countless SNAFUs to take a key village.

By Flint Whitlock

The night of June 5, 1944, was pretty much like every other night in Sainte-Mère-Église since the Germans had occupied Normandy and the Cotentin Peninsula in the summer of 1940: dark, quiet, chilly, and mostly boring.

While there had been innumerable overflights by Allied aircraft (probably taking reconnaissance photos) and the occasional aerial bombing, Normandy was still considered good duty for anyone who had had his fill of war on the Eastern Front and was recovering from wounds psychological and physical.

Here in Normandy there was plenty to eat and drink (especially Calvados, the strong brandy made from apples), scenery that hadn’t been mostly destroyed by heavy fighting, and French people who seemed to, if not exactly warmly welcome, at least be resigned to and tolerate the presence of foreign soldiers on their soil.

When not on actual watch, looking for the first signs of an invasion that might or might not come to this location, the soldiers in Normandy had busied themselves by following Field Marshal Erwin Rommel’s orders to so strongly fortify the coast that the Allied invaders would not stand a chance, that they would, as Rommel had put it, be driven back into the sea.

This night, with the peninsula cloaked in darkness, and the farmers and villagers fast asleep beneath the cloud-obscured moon and the German soldiers—who were on watch in their observation bunkers straining with the help of strong French coffee to keep their eyelids open and scan the black horizon or sound asleep in their barracks or making love to their French mistresses—had no idea what was about to hit them.

If the Allies Could Control Sainte-Mère-Église, They Could Control the Cotentin

A glance at a map of northwest France reveals a basic truth: there are no large cities in the arc between Cherbourg and Caen; only Carentan, Montebourg, Bayeux, and Valognes can be regarded as sizable. A spiderweb of roads connect one town and village and hamlet to another. One town at the center of a web of roads is Sainte-Mère-Église. But the roads—mostly narrow farm roads suitable for bringing produce to market or for driving herds of slow-moving cows from the barn to the fields and back again—also made it hard to move large formations of military vehicles and large numbers of troops.

For centuries—ever since the Vikings or Normans first set foot here, giving the region its name of Normandie—the area has been pastoral and bucolic, with time measured by seasons rather than by the clock. The sturdy homes, shops, and churches are built solidly of stone—a whitish-grayish-yellowish limestone native to the region, capable of fending off the strong winds that blow in fiercely from the North Atlantic and sometimes rattle the shutters and windowpanes. Although treated to the same warm currents that can give southern England a semi-tropical feel (there are, after all, palm trees growing along the English Channel), the winds can sometimes be bitter, and the cold can penetrate through multiple layers of fabric like a gunshot.

The people, too, like their buildings, are a sturdy lot. Hard-working like any agrarian populace, the dour Normans typically rise at (or before dawn), put in a full day’s worth of physical work, eat a hearty dinner topped off with a glass or two of Calvados, and retire at sunset.

The stolid citizens of Normandy were not happy, of course, when, in June 1940, the gray-uniformed Germans marched in and took over, but they accepted their fate the way they accepted most everything that came their way. For the most part, they did not go out of their way to welcome the occupiers, nor did they collaborate with them. They merely tolerated them and went about their usual business of growing the apples that went into the making of Calvados, pulling fish from the Channel, and pasturing their cows, extracting the milk to make into cheese.

It was Sainte-Mère-Église, roughly halfway between Montebourg and Carantan, that had caught the eye of American military planners as early as 1942. Control Sainte-Mère-Église and you control the Cotentin, the planners saw. No fewer than five roads pass through it, plus it was only seven miles from the westernmost amphibious landing beach known as Utah. Drop an airborne division or two, along with their glider-infantry regiments, into the area and you stood a good chance of preventing German reinforcements from Cherbourg in the north and Brittany in the west from slamming into the troops coming ashore at Utah. The western end of the 60-mile-long beachhead that ran from La Madeleine to Ouistreham would thus be secure and the seaborne troops could move inland after overcoming local German opposition. Yes, Sainte-Mère-Église would definitely have to be taken in the early hours of D-Day.

Alexandre Renaud’s Dilemma

In the days before D-Day, Alexandre Renaud was a man with a dilemma. Besides his full-time job as the local pharmacist, the World War I veteran was also the mayor of Sainte-Mère-Église and, as such, he was expected by the occupiers to cooperate with them—and by his constituents to resist. Whenever the Germans gave him an order to do something, such as provide tools, transportation, and laborers to assist in the building of some defensive work, and he could find no one willing to perform the work, punishments would follow.

In May 1944 the Germans were demanding all sorts of things. It was obvious that the local Germans were expecting an invasion and that Sainte-Mère-Église would likely be caught up in it. The roads through the town were filled with trucks towing artillery pieces and carrying troops in all directions. In the fields cordoned off by hedgerows, holes were being dug and large poles were being planted—Rommelspargel (Rommel’s Asparagus) some wag called them—designed to discourage glider landings. Trenches were being dug, and anti-aircraft guns emplaced.

When Renaud spoke clandestinely with townspeople, everyone seemed to have an opinion: the Allies—if and when they attack—will cross at the Pas de Calais, Cherbourg, Le Havre, Dieppe, Boulogne, Dunquerque. Brittany will be the target. No, it will be the Cotentin. Ridiculous—the Allies will feint at Normandy but land on the Belgian coast. Few thought that Sainte-Mère-Église was in any real danger unless Allied bombers decided to target the anti-aircraft batteries that were being installed around the town. After all, air attacks had struck at the bridges at Beuzeville la Bastille and Les Moitiers en Bauptois. Someone else pointed out that leaflets were recently dropped over the area hinting at paratroop landings and showing illustrations of Allied tanks and jeeps and what British and American paratrooper uniforms looked like, and giving instructions on what to do in the event of an invasion. The Allies are probably dropping them all over France, someone else pointed out, just to keep the Germans guessing.

Renaud noted that the digging of trenches around Sainte-Mère-Église was almost completed, but that the Germans didn’t seem to be in any rush. “With the means of punishment at its disposal,” he said, “[the German command] could have made the work go five times as fast, and could have demanded that it should be done by June 1st.”

Throughout May, the presence of German troops increased. Renaud said, “We have seen encamped in our fields infantry, artillerymen, Aryan Germans, and also Georgians and Mongols with Asiatic features … commanded by German officers. In the latter part of May, the artillery units quarter in Gambosville [less than a mile south of Sainte-Mère -Eglise]. The officers come to see me at the Town Hall. They need spades, picks and saws immediately. The town is to be secured, and the work has to be finished in five days.

“I reply that there are no more spades or saws in the neighborhood and that they will have to canvass all the houses in order to find a few tools. They phone the Feldcommandantur at Saint Lô to get instructions about what punitive measures to take. He gives an evasive answer. Discouraged, they finally go to a hardware store where, after threatening to loot everything, they manage to obtain a few tools. Guns are then installed at all the town approaches; on the Carentan road, on the La Fière road, before Capdelaine, on the Ravenoville road.

A wonderful tribute to your Dad's and all the other brave Troopers that jumped that night!

ReplyDeleteThey fought fascism then..we fight Trump fascism and christofascism today. Vote blue to save the planet from orange Hilter and his mentally disordered mob of sub-apes.

ReplyDelete