On National Coming Out Day, I'm pleased to reprint Michael Bedwell's article on my late mentor, Dr. Franklin Kameny, Ph.D.

I was honored to have Frank Kameny speak on an American Bar Association Annual Meeting program in Chicago in August of 1990 on security clearances, and to help inspire two House subcommittees to invite him to speak at one of the five days of our security clearance hearings.

Ever since I first met him, Frank inspired me:

- In 1989, USDOL Chief Judge Nahum Litt and I helped win passage of an ABA House of Delegates resolution on security clearances in Honolulu in August of 1989.

- In February 1989, Chief Jude Litt and I helped save the ABA House of Delegates resolution on Gay rights.

- During 1989-90, I prosecuted the case of Duane Rinde v. Woodward & Lothrop, winning the first ever equal rights case against a corporation.

- In 1990, I was invited to write the first article on Gay Marriage for an American Bar Association publication.

- In 2005, I helped win a federal court First Amendment decision requiring Rainbow flags on the Bridge of Lions.

- In 2019, I helped persuade the St. Augustine Beach City Commission to fly a Rainbow flag for Gay Pride month.

- In 2012, Ihelped persuade the City of St. Augustine to add sexual orientation as a protected class to its Fair Housing Ordinance.

- In 2013, I helped persuade the City of St. Augustine Beach to forbid discrimination in housing and employment on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity,

From LFBTQ Nation:

LGBTQ HISTORY

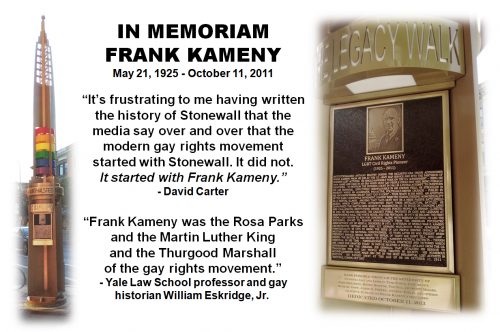

Frank Kameny devoted his life to fighting for gay rights. He lived to see the end of DADT.

Frank KamenyPhoto: Kameny Papers - Library of Congress

The sadness of Frank Kameny’s inevitable passing in 2011 was assuaged by the beautiful symmetry of it happening on National Coming Out Day. These are some of my very personal memories.

“We know that every heart eventually gives out, but we know, too, that all of us have the power to preserve the memory of that heart, mind, and spirit that guided us closer to the equality for which we still aim.” – Rainbow History Project Chair Philip Clark.

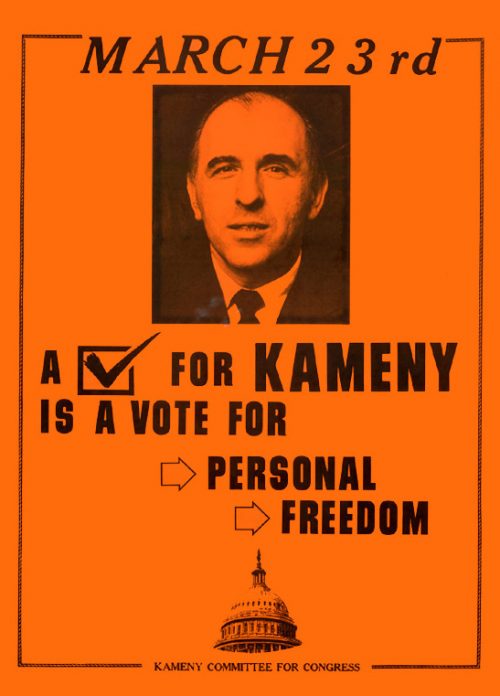

For those unaware, Frank came to the movement later than some, bursting publicly out of the closet in 1961. He’d been fired for being gay by the Army Map Service in 1957; shooting down his dream of becoming one of the first astronauts and making his Harvard degree in astronomy virtually useless even in civilian companies because their federal contracts prevented them from hiring gays. He was plagued by periods of poverty for the rest of his life.

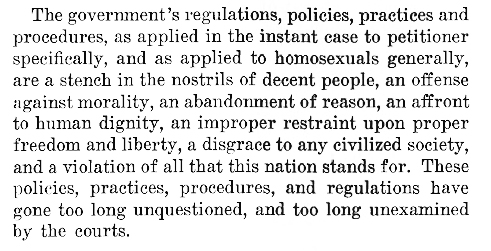

Turned away by every government agency he appealed to, his own attorney giving up; Frank pushed on. With no previous involvement in activism, wrote his own final brief with furious eloquence; the first gay person ever to appeal their firing to the United States Supreme Court; foreshadowing his decades of activism that followed.

“I have resented for over 60 years that I had to lie to fight for my country during World War II.”

Nine years before Stonewall he told the Supreme Court: “In World War II, petitioner did not hesitate to fight the Germans, with bullets, in order to help preserve his rights and freedoms and liberties, and those of others. In 1960, it is ironically necessary that he fight the Americans, with words, in order to preserve, against a tyrannical government, some of those same rights, freedoms and liberties, for himself and others.”

The Court denied him a hearing, radicalizing him, and, within months, he and Jack Nichols, then 36 and 23 respectively, cofounded the Mattachine Society of Washington (MSW), which, contrary to years of misstatements, was not a chapter of National Mattachine.

An actual Washington chapter, founded by others in 1956 but defunct by 1961, had been told by National to limit their activities to “research and education” and to abandon its “Repeal of Unjust Laws” mission or lose its charter.

Frank and Jack had no intention of duplicating such timidity. Mattachine was included in their name only for its familiarity in the community. MSW’s initial goals were repealing unjust laws and regulations that mandated federal employment discrimination in the civil service, in security clearances, and in the military.

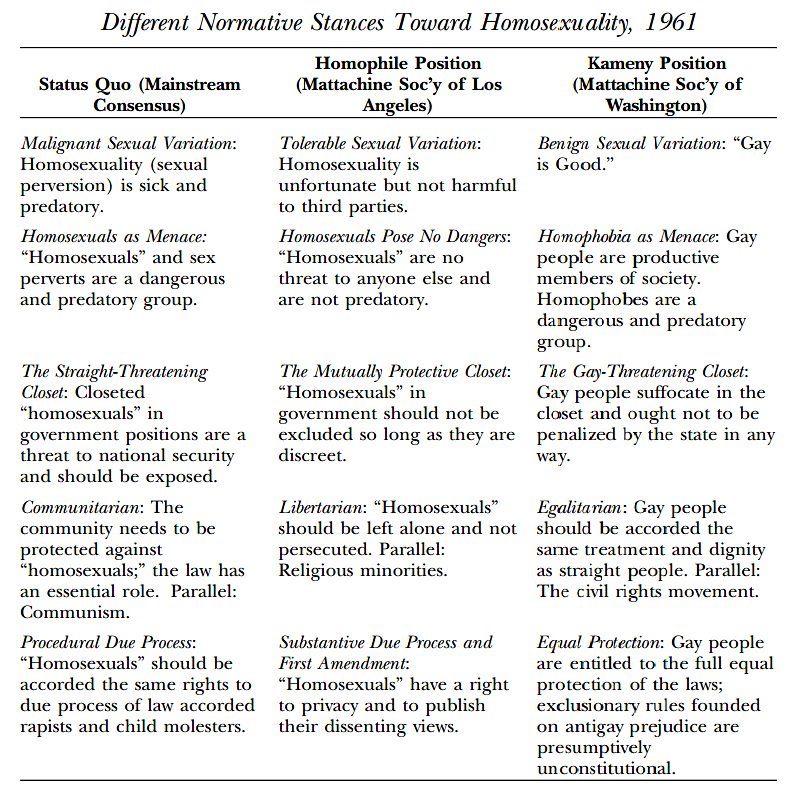

Yale law professor and historian William Eskridge contrasted Frank’s beliefs which shaped MSW and ultimately the entire movement with the status quo in Gaylaw: Challenging the Apartheid of the Closet.

“We all did a lot, but all roads led to Frank. He was behind everything.” – Kay Tobin Lahusen, pioneer out lesbian photojournalist and cofounder of New York’s original Gay Activists Alliance.

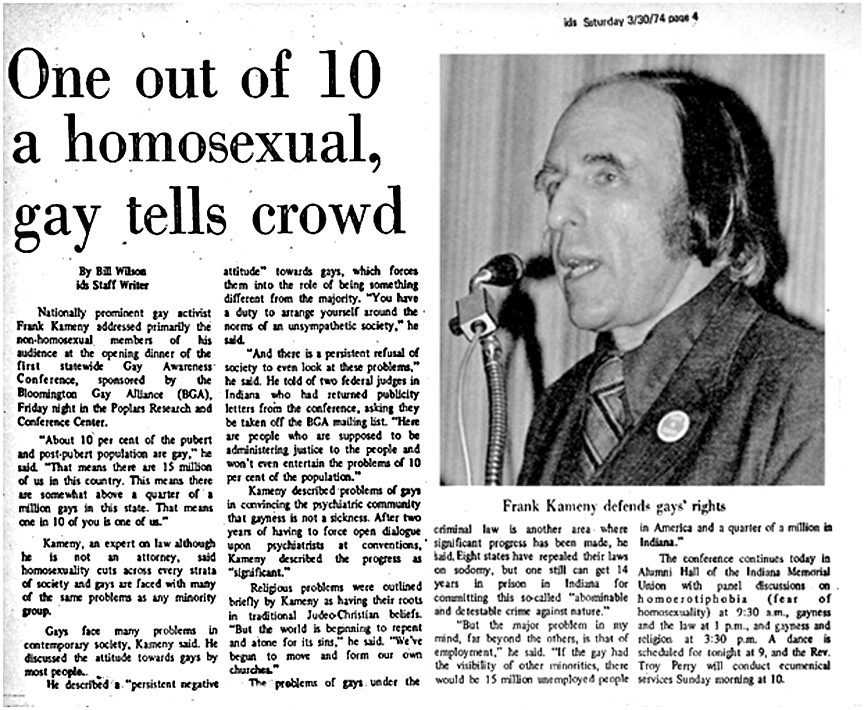

We first met when I picked Frank up at the Indianapolis airport in March 1974. He was the keynote speaker at the Gay Awareness Conference sponsored by Bloomington Gay Alliance on the campus of Indiana University (IU).

At 48, he was considerably past Generation Stonewall, but, even pre-Internet, his reputation as a pre-Stonewall pioneer was well known to us and kept him busy with speaking engagements across the country; going from town to town like a gay Johnny Appleseed planting self-acceptance, resistance to oppression, and demands for change.

Five years before Stonewall he’d declared: “We are dealing with an opposition which manifests itself — not always, but not infrequently — as a ruthless, unscrupulous foe who will give no quarter and to whom any standards of fair play are meaningless. Let us respond realistically. We are not playing a gentlemanly game of tiddly-winks or croquet or chess.”

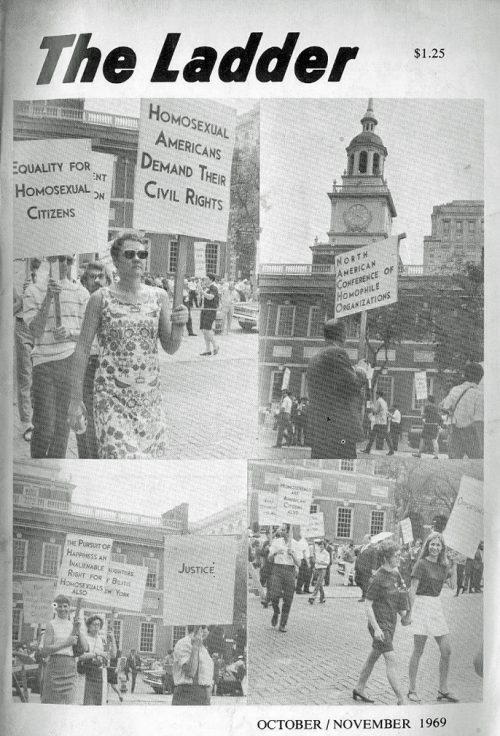

By the time we met he had already led the first ever gay rights protests outside the White House – at a time when a still deeply publicly closeted Harvey Milk was still mourning that a Republican wasn’t in the White House – Pentagon, State Department, Civil Service Commission, and Independence Hall in Philadelphia.

By the time we met he had refused the demand of infamous FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover that MSW stop sending him their newsletter, and rescued a lesbian from a psychiatric clinic where she had been taken for electric shock therapy to “cure” her after literally being kidnapped by her parents.

Insisting it was not enough just to say being gay wasn’t bad, he had coined the term “Gay Is Good.”

By the time we met, he had been featured in national mainstream news magazines and a national TV “documentary.”

He had also been one of the cofounders of four national gay rights organization associations, and Gay Activists Alliance of Washington and the National Gay Task Force.

“Kameny is truly a giant of the movement and he was the main militant in the movement before Stonewall. What really happened is that Kameny throughout the sixties was being listened to more and more, but not only was the movement gripped by the mentality that we were criminals and we were mentally ill, and Frank and others had to fight very hard to overcome that, but the movement was microscopic in size. He created this new rhetoric. He called himself and his colleagues in the group ‘homosexual American citizens’, and said that you can’t forget either part of that. In the very first thing he wrote, back in early 1961, his brief to the Supreme Court, he argued not only that the government should not persecute homosexuals but should work to end discrimination against them; that the homophile movement was a civil rights movement that must settle for nothing less than full legal and social equality. No one had ever enunciated that approach before. It was beyond radical for its time. My perspective is that when Stonewall precipitated the gay liberation movement, the movement then caught up with Frank.” – David Carter, Stonewall historian.

By the time we met in 1974, he had been the first out gay person to testify in a Congressional hearing and the first out candidate for a seat in Congress.

He was the only person in the country regularly trying to help LGB service members avoid a less than honorable discharge.

“MAKE THEM HEAR YOU”

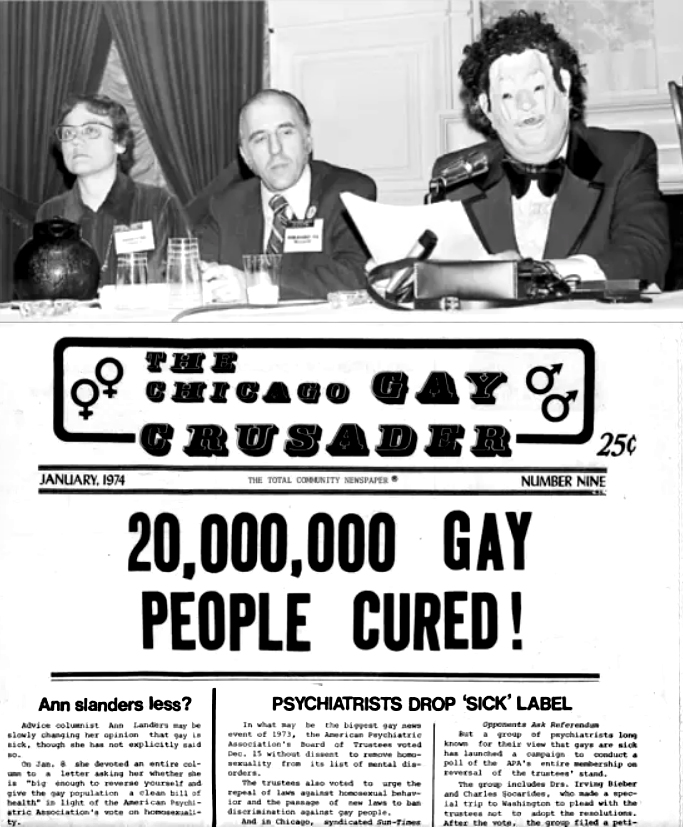

By the time I met him, he had participated in a “zap” at the 1971 annual convention of the American Psychiatric Association, commandeering the stage, and – even after they unplugged the microphone – his stentorian voice trumpeted above the pandemonium and attendees’ angry shouts for him to get out, telling them, “Yes, we are sick – we are sick of your manipulation and exploitation of us. Psychiatry is the enemy incarnate. Psychiatry has waged a relentless war of extermination against us. You may take this as a declaration of war against you.”

He announced eight demands, including the removal of homosexuality from the APA’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, which, two years later due to his and compatriot Barbara Gittings’ persistent uncompromising lobbying and education they did.

Establishing that we were no longer “sick by definition” was the single most important victory in the history of the movement, and the one from which all other victories have flowed.

At the airport, the unique tenor, power, and self-confidence of his speaking voice was my first impression. And he taught me my first lesson in the movement when I asked him what he thought about the rumors that someone just beginning to gain some national prominence was only into it for self-aggrandizement and financial gain.

His immediate response: “I’ve heard those rumors, too, and I don’t care if they’re true as long as what he does is good for the movement.”

His speech was thrilling; the kind of real, live, in the moment call to action that all of us had only read about, never had the chance to hear on Indiana TV or radio.

“I’m told Bloomington doesn’t have a gay rights ordinance. Why not, and what are you going to do about it?!” he asked.

[A little more than a year later, city council member Brian de St. Croix, who’d heard Frank’s speech, had come out publicly and introduced and got passed the state’s first and the country’s 26th such ordinance during a raucous meeting in which Bibles were literally waved at Brian and other members of the council. He was soon inundated with written and telephoned death threats.]

A few weeks after our conference, Frank took part in the first nationally televised debate on marriage equality.

Neither of us knew when we first met that Frank would also be responsible for indirectly bringing into my life one of the friends I have loved most, someone whom civil rights activist and author Malcolm Boyd called “the Charles Lindbergh of the Gay Movement.”

About the time of our 1974 conference, Sgt Leonard Matlovich, United States Air Force, saw an article in the Air Force Times about homosexuals in the military in which Frank was quoted saying he was looking for a perfect test case to challenge the ban on gays.

Though having been barely out to himself a year, Leonard called Frank, eventually offering to be the subject of the challenge with his perfect record including three tours of duty in Vietnam, a Bronze Star, and Purple Heart.

Outing himself to the Air Force the next spring, his story exploded in newspapers, magazines, and television news, most famously still on the cover of TIME magazine.

“When Leonard Matlovich was on a magazine cover as a war hero, challenging the policy in the military, it began a national discussion on gay rights.” – Gay historian Nathaniel Frank

After he was discharged, he spoke at our 1975 Gay Awareness Conference at IU; we became friends, then roommates when I moved to Washington DC in 1977.

There, I joined the Gertrude Stein Democratic Club which Frank had also co-founded, and he came to several events at our home.

Leonard and I were later roommates in San Francisco, too. He passed from AIDS in 1988. Frank was an honorary pallbearer, walking by the horse drawn caisson carrying Leonard’s coffin through the streets of Washington, and spoke at the graveside service in Congressional Cemetery.

In 2005, I saw him at the Equality Forum celebration in Philadelphia and photographed him with former US Ambassador James Hormel, Tim Wu, and Chip Arndt in front of a screaming swarm of religiofascists trying to drown out the speakers.

In 2007, his tens of thousands of items of movement memorabilia were acquired by the Library of Congress and Smithsonian.

In 2009 he was the speaker I wanted more than any other at the Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell (DADT) protest and memorial for Leonard I organized in conjunction with the National Equality March on Washington.

Over 200 attendees of various ages were already at the Cemetery, standing in front of the lectern, when I arrived with Frank, and I will never forget the palpable feeling of awe and respect from them as he walked to his seat nor the applause for him before he spoke.

Nor the last thing he said: that, at 84, he hoped he lived long enough to see the ban end.

Later as we stood side-beside as gay veterans Dan Choi and Mike Rankin placed a wreath on Leonard’s grave with its famous headstone reading “When I was in the military they gave me a medal for killing two men and a discharge for loving one” I wondered what was going through his mind having outlived his protégé and so many others.

2009 also saw him saluted at White House Pride by President Obama for dedicating his life to gay activism. And he received a symbolic apology for having been fired in 1957 during the Eisenhower Administration that led to his joining and revolutionizing the movement.

The next time I saw him was 2011 when I was in Washington again for a court appearance in relation to my arrest along with twelve others from around the country during a protest at the White House the previous November of the President’s slow walk of DADT repeal. I called to invite him to a small fundraiser for our various expenses.

When we arrived, the reaction of the attendees was, if anything, stronger than it had been at the 2009 event because no one knew he was coming. Like a silent electric wave, the same look passed from face to face – “That’s Frank Kameny!” – as he walked by them.

Driving him back to his house afterward, I struggled for courage and a way to tell him something with the least likelihood of hurting him by reminding him of his mortality.

Recently I had learned that the plot next to Leonard’s grave was for sale, and I bought it immediately, imagining someday people from around the world being able to pay homage to them together. Leonard had become more famous but without Frank he might never have become the activist he did.

We were almost to his door when I explained, adding that I was offering it to him for free. Clearly a bit taken back, he said he hadn’t thought about such things very much but thanked me and said he’d think about it and let me know.

As he disappeared behind the door of the house that was already a D.C. Historic Landmark, I teared up a little, thinking back to that first time I’d met him 37 years before, and wondering if I’d ever see him again.

I hadn’t heard from him by the time he passed that National Coming Out Day – barely a month after getting that final wish: to see the military ban he’d fought for 50 years finally ended.

I contacted his friends in Washington arranging for his funeral, and offered them the plot. Another in the row immediately behind Leonard was purchased by the nonprofit Helping Our Brothers & Sisters (HOBS) which had often helped him financially in recent years.

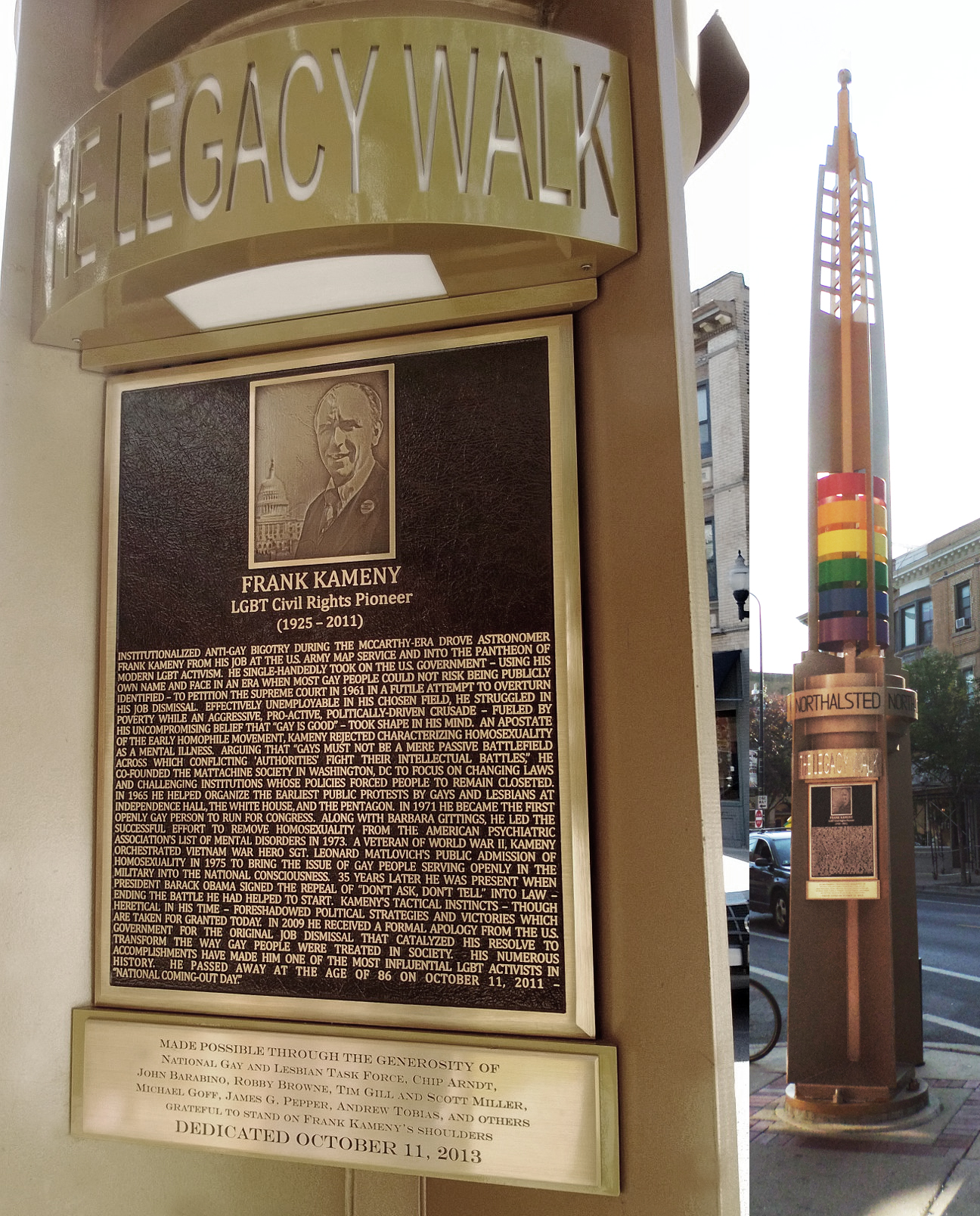

In 2013, Chip Arndt whom I’d photographed with Frank in 2005 and I raised money for a memorial to him along Chicago’s Legacy Walk, the world’s only outdoor museum of LGBT history. It was placed next to one already installed for Leonard.

In 2015, after his heir refused to release any of his ashes to the group who’d planned his internment in Congressional Cemetery, a memorial stone, a cenotaph, designated for someone whose remains are elsewhere, was provided by the Veterans Administration, and I organized the dedication ceremony as a part of the annual LGBT Veterans Day Observance next to Leonard’s grave.

Before his stone was unveiled, the Gay Men’s Chorus of Washington DC, who had performed at Leonard’s funeral, sang the song whose words perfectly summed up Frank’s life. [Their performance in this video was two years before.]

I hope I live long enough to see him posthumously receive what he should have in life: the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

“Remember your roots, your history, and the forebears’ shoulders on which you stand.” – Marion Wright Edelman.

Images courtesy of Kameny Papers - Library of Congress, Michael Bedwell collection and Screen Capture "The Lavender Scare"

No comments:

Post a Comment