Phillip Allan Lacovara is a great American, a skilled appellate lawyer who helped the Watergate prosecutor bring down a corrupt President. I got to know him during 1989-1991, when he and I served on the Council of the American Bar Association Section of Individual Rights and Responsibilities, where I was the Liaison from the Young Lawyers Division. While Phil and I disagreed on some issues, I found him to be a force for good in ABA. History will record that I was right in opposing this corporate lawyer's extravagantly claiming that environmental protection was outside our Section's jurisdiction and "not a human rights issue)". From The American Bar Association Journal:

Philip Lacovara: "When the Nixon case was decided, I thought that while it would give subsequent presidents the opportunity to claim executive privilege, which was not an established doctrine, I never thought it would lead to a former president claiming immunity from criminal prosecution. Yet here we are."

Philip Lacovara remembers many details from his oral argument in United States v. Nixon, which took place nearly 50 years ago. The unanimous 8-0 decision, which held that President Richard Nixon was not immune from a special prosecutor’s subpoena for tapes relating to the Watergate scandal, marked the beginning of the end of his administration. But it also recognized executive privilege, which had previously been a murky and vague issue, as a constitutional right that could be invoked for national security purposes—handing a powerful weapon to subsequent presidential administrations.

The 80-year-old Lacovara recalls how, as counsel to the Watergate special prosecutor, he was the final speaker during oral arguments, taking the podium after two of the most well-known attorneys in the country: James St. Clair, who represented Nixon; and Leon Jaworski, the special prosecutor. Lacovara understood the stakes and knew that the fate of the Nixon administration lay in the balance.

He remembers how he structured his arguments to try and appeal to the eight justices who would, essentially, determine the fate of the Nixon administration. (Justice William Rehnquist, who had served in Nixon’s Department of Justice, recused himself.)

He even looks back fondly at a moment of levity that helped cut the tension before the big moment.

“I wore my best blue suit,” recalls Lacovara, who would later serve as vice president and senior counsel for litigation and legal policy for General Electric Co.; as managing director and general counsel for Morgan Stanley & Co. Inc.; and as a partner at Mayer Brown. “I noticed there was a thread hanging, and my secretary said she would take care of that. She took out these giant shears, she was a little nervous, and ended up lopping off a half inch of my suit coat. So I argued the case with my suit having been horribly abused! I thought it was hysterical.”

What’s not a laughing matter for him, though, is the upcoming Trump v. United States case before the U.S. Supreme Court, which could dramatically expand the scope of presidential immunity. Lacovara felt strongly enough about the case that he signed an amicus brief alongside former Donald Trump White House attorney Ty Cobb, Mike Pence adviser Olivia Troye, former U.S. Attorney Patrick Fitzgerald and others, arguing against the notion that former presidents had criminal immunity.

Lacovara spoke with the ABA Journal about his experience with U.S. v. Nixon and his concerns about the Trump case. Responses have been edited for clarity and brevity.

So did you think you’d ever have to deal with this again?

No, not in a million years! When the Nixon case was decided, I thought that while it would give subsequent presidents the opportunity to claim executive privilege, which was not an established doctrine, I never thought it would lead to a former president claiming immunity from criminal prosecution. Yet here we are.

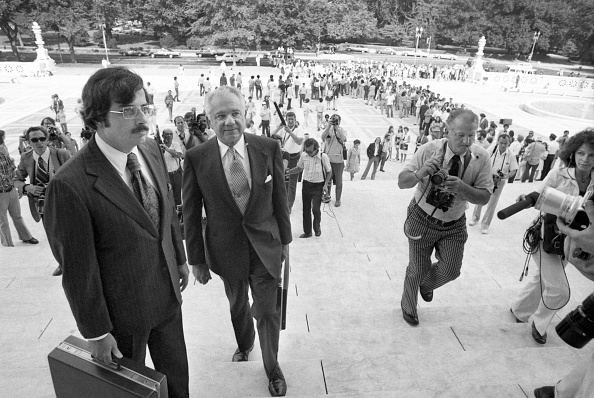

Philip Lacovara (left), counsel to Watergate special prosecutor Leon Jaworski, and Jaworski himself enter the U.S. Supreme Court to argue for the release of 64 presidential tape recordings. (Photo by Bettmann Archive/Getty Images)

Philip Lacovara (left), counsel to Watergate special prosecutor Leon Jaworski, and Jaworski himself enter the U.S. Supreme Court to argue for the release of 64 presidential tape recordings. (Photo by Bettmann Archive/Getty Images)Talk to me a bit about how you got involved with the U.S. v. Nixon case.

Lacovara: I was counsel to the Watergate special prosecutor. Originally, I was hired by Archibald Cox, who was the first special prosecutor. I had been in the solicitor general’s office as deputy for criminal cases. Cox had served as solicitor general under John F. Kennedy and looked to that office and invited me to join his staff. By the time the second round of tapes was subpoenaed, which was relevant to the case that went to the Supreme Court, Cox had been fired and replaced by Leon Jaworski, a Texas trial lawyer who was not a constitutional lawyer. So I was responsible for drafting the brief and co-arguing the case with Jaworski.

Did you understand or appreciate how important this case was at the time you were preparing for it?

Of course. This was at a time when there were no cable networks, so people had to follow Watergate on the three networks and in the major newspapers and news magazines of the day, and Watergate got front-page attention day after day. It was well understood that the fate of the Nixon presidency turned on how the court would resolve the case. We were very focused on how we would present our case and how we would act and behave. For instance, we made sure we sat where the solicitor general usually sits in order to convey to the court that we were acting on behalf of the United States. We also made sure we filed first in the Supreme Court so that the case would be captioned “United States v. Nixon.” That was part of our litigation strategy of conveying to the court that we were acting on behalf of the U.S., and Nixon was simply a witness who had material evidence that we needed.

How worried were you that Nixon would just simply refuse to follow the Supreme Court if it ruled against him? Especially if the decision wasn’t unanimous?

Very worried. That was exactly the point that Nixon had been arguing, that he as the head of a coordinate branch of government did not have to necessarily accept the court’s views of his constitutional powers. Basically, he was arguing that the court decides what its role is, and the president decides what his role is—and in the absence of a “definitive” decision, he reserved the right to determine whether or not to turn over the tapes. Because of that, I carefully ended my oral argument—I was the last speaker—by inviting the court to render a definitive decision rejecting his claim.

Were you satisfied with the court’s decision? Or were you pleased with the result but upset with their reasoning?

Well, as we now know, in order to get a unanimous decision, there was lots of horse trading within the conference. In essence, the presidency won, but Nixon lost. The justices agreed with the pro-Nixon camp that there is executive privilege, which had never been established before, but that it’s a constitutionally based privilege that is not absolute. For that reason, all the mischief that has happened over the last 50 years is traceable to that. I thought then and now that the concept of executive privilege is probably unfounded. Many people conduct all kinds of operations in government and in the private sector without having privileges against disclosing that information. But I can see the reason behind it, given the fact that there are some other confidential privileges accepted under our common law, like attorney/client and priest/penitent privileges.

Turning to the Trump case, are you concerned that there might be some justices on the Supreme Court that agree with him?

I think Trump has some plausible intellectual support within the court, certainly among the people who are big supporters of presidential prerogatives. There is an arguable view that a president should not be called into question through the criminal process for actions he took in exercise of clear presidential power. So part of the issue in the Supreme Court case is whether what he did in connection with Jan. 6 and the run-up to it actually constituted an exercise of bona fide authority or was purely private political activity. It’s hard to define a line that would insulate a president from criminal liability for certain kinds of presidential activities while keeping him exposed to prosecution for things we would never want to tolerate. As to how some justices might rule, I’m concerned that there might be at least some support for him on the court, and that’s indicated by how they reformulated the question, which is to ask whether the Constitution provides immunity for actions that are allegedly within the scope of presidential power. The way they formulated the question was if the former president alleges that he was acting as president, is there constitutional immunity? That’s the most indulgent formulation for Trump’s benefit. I’m pretty certain there are some justices who want to see Trump exonerated or spared from criminal trial.

Were you surprised to see the court take the Trump case? They could have just let the D.C. Circuit decision stand and declined to wade into such a controversial political issue.

Definitely. I thought, if there were a legitimate reason for taking the case, then they should have responsibly taken it in December when [Special Prosecutor Jack Smith] asked them to take it rather than wait a couple of months, which is part of Trump’s strategy. I was not surprised they decided to hear it, since it’s an important issue—although I would hope that this is a one-off in our nation’s history and that this the only time we’ll have a president plausibly subject to prosecution for crimes while in office.

No comments:

Post a Comment