Stetson Kennedy, unmasker of the Klan

Kennedy was a courageous writer and activist for racial justice. But more, he was a champion of that passing 'other America'

You wouldn't think it to look at us now, but the United States used to grow a fine crop of progressives.

Stetson Kennedy, who died 27 August at the age of 94, was one of the great ones. Political provocateur, author of books on social justice and folklore, civil rights campaigner, friend of Zora Neale Hurston, Jean-Paul Sartre and Woody Guthrie, subject of a Billy Bragg song, southern gentleman and object of constant death threats from angry racists, Kennedy dedicated his long life to the struggle for equality. According to historian Gary Mormino, "At one time Stetson Kennedy was the most hated man in America." He was also a genuine American hero.

Kennedy is most famous for infiltrating the Ku Klux Klan in the 1940s. Denied the chance to fight fascism in the second world war because of a bad back, he decided to fight it at home. He impersonated an encyclopedia salesman and joined a "Klavern", swearing to "uphold the principles of White Supremacy and the purity of White Womanhood." He funnelled information on Klan rituals (a juvenile mix of Freemasonry and college fraternity, complete with secret handshakes, elaborate titles and a rule book called "The Kloran") and, more importantly, whatever violence they were planning, to the police, the Anti-Defamation League and the Washington Post. He gave closely guarded Klan passwords to the writers of the popular "Superman" radio show, who used them in a story line in which the "Man of Steel" battles the hateful forces of the Grand Dragon.

In 1946, Kennedy wore his white robe and hood to crash a meeting of the House Un-American Activities Committee. He wanted them to investigate the Klan. They had him thrown out of the capitol. Mississippi Congressman John Rankin, chair of Huac, said, "After all, the KKK is an old American institution."

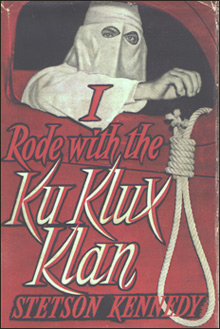

Cover image of Stetson Kennedy's I Rode With the Ku Klux Klan (1954), later renamed The Klan Unmasked. Photograph: Kennedy Archives

Cover image of Stetson Kennedy's I Rode With the Ku Klux Klan (1954), later renamed The Klan Unmasked. Photograph: Kennedy Archives Kennedy published two books based on his undercover activities, Southern Exposure in 1946 and in 1954, the lurid I Rode With the Ku Klux Klan, written in hardboiled detective style (it was later retitled The Klan Unmasked). He became Klan Enemy No 1, with Grand Dragon Sam Green offering a reward for killing him: "Kennedy's ass is worth $1,000 a pound!"

William Stetson Kennedy was a traitor to his race and to his class. What's more, he was proud of it.

He was born in 1916 to a well-off Florida family, a descendant of plantation-owning signers of the Declaration of Independence, Confederate officers and John Batterson Stetson, maker of the famous cowboy hats. He recalled that when he was a child in the 1920s, local Klan thugs beat and raped the beloved Kennedy family maid for "sassing whitefolks". Perhaps that spurred his precocious antipathy to the racial politics of the south: "At a very tender age, I became aware that grownups were lying about a whole lot more than Santa Claus."

In 1936, while a student at the University of Florida, he collected boots and blankets for the Republican side in the Spanish civil war. In the late 1930s, he went to work for the federal writers project of Franklin Roosevelt's Works Progress Administration collecting folklore with Zora Neale Hurston, later famous for her novel Their Eyes Were Watching God. Together, they'd travel the back roads, the revolver-packing black preacher's daughter and the word-besotted Confederate general's grandson, collecting the rapidly disappearing tales of Old Florida, stories of voodoo, talking alligators, jook joints and neo-slavery in the turpentine camps. In an interview in 2004, Kennedy recalled, "Zora and I were at a camp near Cross City where we met this octogenarian who'd been born 'on the turp'mntine.' I asked why he didn't just leave, and he said 'the onliest way out is to die out and you have to die 'cause if you tries to leave, they'll kill you.'"

His WPA material became the basis of his first book, Palmetto Country, published in 1942. Woody Guthrie, whose "This Land is Your Land" is still beloved of schoolchildren who have no idea they're singing a socialist anthem, fell in love with Kennedy's work. The proletarian troubadour who inspired Bob Dylan sent Kennedy a Joycean fan letter, asking for songs he'd collected – "the sort that make the wives of senators faint when they hear them" – praising Kennedy's "lecturetalks against the KKK and all the rest of the stoolies, gooners and fonies in general, the raceyhaters, pinkybaiters, deadbrainers, and fraidy cats."

The McCarthyite, Jim Crow America of the 1950s wasn't exactly friendly to the likes of Stetson Kennedy. New York publishers would touch him, and besides, the Klan had tried to burn down his house in Florida. So he left for Paris, where he got to know black writer and fellow southerner Richard Wright, and Jean-Paul Sartre who helped him publish The Jim Crow Guide to the USA. Meanwhile, Woody Guthrie, always in need of a place to stay, wrote dozens of songs there, but also stationed a shotgun by the front door in case the Klan came calling.

Stetson Kennedy's house "Beluthahatchee" still stands by a lake ringed with cypress trees full of snowy egrets and osprey. The name comes from a black Seminole folktale collected by Zora Neale Hurston – Beluthahatchee is a sort of Garden of Earthly Delights, a place where "all is forgiven". After wandering for a decade, Kennedy came home to Florida, determined to find what he called "the other America", the one "envisioned by the Founding Fathers and Lincoln, Whitman, Guthrie, Robeson et al. Which is to say a democratic society and government functioning for the common good of the people, as opposed to megaprofit for the few."

He joined lunch counter protests in southern cities throughout the 1960s and agitated for environmental protection until he went into hospital for the last time. In 2006, the authors of Freakonomics, who based an admiring chapter on Kennedy's The Klan Unmasked, concluded they had been "hoodwinked", and challenged his account of Klan infiltration. This ignited a fiery protest, with Studs Terkel angrily defending his old friend in a letter to the New York Times:

"[Stetson] could well be described as a 'troublemaker' in the best sense of the word. With half a dozen Stetson Kennedys, we can transform our society into one of truth, grace and beauty."

Investigations by several newspapers, and evidence from Peggy Bulger, director of the American Folklife Centre at the Library of Congress, generally exonerated Kennedy.

In his tenth decade of life, Stetson Kennedy would say, "I like to think I haven't mellowed." He hadn't: he was still marching for farmworkers' rights at the age of 93. In hospice care a few days ago, a doctor came into check his mental facilities: "Where are you from?" said the doctor. Stetson Kennedy replied, "Planet Earth."

- © 2011 Guardian News and Media Limited or its affiliated companies. All rights reserv

No comments:

Post a Comment