Thoughtful article from GANNETT's Palm Beach Post. Thanks to local celebrations of St. Augustine's African-American history, I attended my first Juneteenth celebration in West Augustine, circa 2009.

From Palm Beach Post:

Reflections on Juneteenth: Black civil rights and the influence of fatherhood

Wayne Washington

Wayne Washington

This year, Father's Day falls on the newly minted federal holiday of Juneteenth.

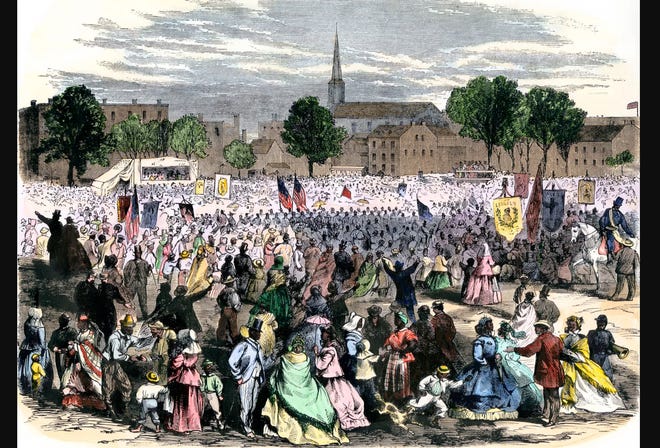

For generations, Juneteenth or "Jubilee Day" has been celebrated by Black Americans in remembrance of June 19, 1865, when enslaved ancestors in Texas learned from a Union military unit that an executive order had ended their bondage.

Two and a half years earlier, Abraham Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamationhad declared that enslaved Black Americans in states rebelling against the Union were free.

The proclamation was a moral and political thunderclap; but its true, lasting power wasn't known until after the Civil War had been won and recalcitrant slave owners were forced to give up their human property.

History knows well many of those who made Juneteenth possible — men and women who marched, wrote, spoke, fought and died for the freedom the holiday would come to commemorate.

What is a bit less well understood is the personal toll the fight for freedom and, later, for equality and advancement, took.

On this Father's Day, an examination of their writings and speeches shows that, for many of the most revered Fathers of the Fight, their work was driven by dreams for a better life for their own children almost as much as it was for their people as a whole.

The Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. underscored that reality in his "I Have A Dream"speech, drawing on the deeply personal to lay out what type of country he hoped his advocacy would help create.

Black fathers face unique challenges

In that, the great Black men of American history lock arms with brethren who won't win a Nobel Prize, advise presidents or serve on the U.S. Supreme Court.

"The historic and present reality of African-American fathers raising Black children in America has always been fraught with dual concerns — normal and the racially abnormal," said Keith Berry, dean of academic affairs for Hillsborough Community College's Ybor City campus. "Strengthening and shielding children from the potential pitfalls of American life while enlightening others in the process is equally a burden and gift."

Berry, himself a Black father who has both a master's degree and a doctorate in American history, noted that many of the Black men who would rise to become scholars and advocates took their early cues from their own fathers.

He pointed to famed historian John Hope Franklin, whose father, attorney Buck Colbert Franklin, had his law office on the second floor of a building in the Greenwood section of Tulsa, Oklahoma, made infamous in 1921 when it was burned down in a horrific race massacre.

"Young Franklin took great pleasure as a child going to that office to clean it and sit and talk to his father," Berry said. "On trips to the courthouse with his father, attorney Franklin purposefully did not allow his son to yield to segregation because he would not seat his son in the designated area for Blacks."

After the race massacre, Franklin's father provided legal services to the Black community from a tent.

His son was paying attention.

"Certainly, this environment and its aftermath were not lost on young John Hope, who went on to become a noted scholar of American history in addition to being a Fisk University and Harvard University graduate," Berry said. "Franklin was an activist scholar who did background research as a historian, for the Brown decision of 1954; and eventually Franklin was awarded a Presidential Medal of Freedom after serving on a race relations committee at the behest of the president of the United States."

Hiding the scars from your children

While Franklin was more inspired than intimidated by his father's prominence and contributions, that hasn't always been the case.

It was often not the case for the children of the most prominent anti-slavery orator of the 19th Century, Frederick Douglass.

Born into slavery in Maryland before escaping to freedom, Douglass started an anti-slavery newspaper, The North Star, and traveled throughout the North and even to Europe pushing for emancipation.

Douglass wasn't just writing and talking. He had what would today be called the receipts on slavery's evil — scars that marred his back, scars angrily laced there by white men who tried to subdue him during his years as a slave.

Armed with that personal, painful knowledge of slavery, Douglass was as forceful as he was eloquent. He came to love what Lincoln represented — hope that white powerbrokers would take up the cause of freedom. He also loathed Lincoln's pre-1863 diffidence on emancipation.

Douglass and his wife, Anna Murray Douglass, had four children: a daughter, Rosetta, and three sons, Lewis, Frederick Jr. and Charles.

Each of his sons joined the Union military, with his youngest, Charles, becoming the first Black soldier to enlist in the state of New York.

In his 2018 biography of Douglass, "Frederick Douglass, Prophet of Freedom," historian David W. Blight painted a complicated picture of the relationship between the great orator and his children.

Along with Rosetta's husband, Nathan Sprague, Douglass' children relied upon him financially even into adulthood, much to his consternation.

Douglass' long absences from home pushed the cause of freedom forward even as they retarded his relationship with his children.

Of Rosetta, Blight wrote: "A picture emerges from her perception of a father so consumed by his work and his cause that he could never see her dilemmas, nor hear her cry."

Blight also examined Douglass' relationship with his sons.

"While worshipping their father, the sons carried their own burdens of being Douglass's offspring," Blight wrote. "Each eagerly sought a father's love and approval."

Losing a Black dad too soon

Unlike Douglass, Malcolm X was assassinated before his children reached adulthood. In fact, he was shot to death in 1965 as his pregnant wife and four children took cover from the front row of the Audubon Ballroom in New York, where he was making a speech.

Like advocates before and after him, Malcolm X's travels kept him from being a daily presence in his children's lives.

"My mother set the rhythm in our household, and, at least from the perspective of the child, my father was certainly a supporter and a contributor to what the energies were in my household," one of his daughters, Attallah Shabazz, was quoted as saying in 1994's "Malcolm X, Make It Plain," a book of pictures and quotes about the civil rights leader. "But since it was my mother who was the housewife and round-the-clock role model for me, my mother was my first love. My father was my first buddy."

More than many other advocates, Malcolm X talked directly about Black manhood in general and Black fatherhood in particular.

"Be a man," he urged in one of his speeches. "Earn what you need for your family. Then, your family will respect you. They are proud to say, 'That's my father.' She is proud to say, 'That's my husband.'"

He added: "Father means you are taking care of those children. Just because you made them doesn't mean you are a father. Anyone can make a baby, but anyone can't take care of them. Anyone can go get a woman, but anyone can't take care of a woman. Husband means you are taking care of your wife. Father means you are taking care of your children. You are accepting the responsibilities of manhood."

Even though she was only 6 at the time of her father's murder, Attallah Shabazz said his memory remains vivid.

"He was actually a mush, a real pushover, when it came to his girls,” she said in a 1989 interview with The Los Angeles Times. "You were never a bad girl. You could make many mistakes. You know when you’ve done something wrong as a kid? You get a knot in your stomach? I didn’t have that. I felt like I could tell him anything. And if you came in with mud on your face, you didn’t feel like you were dirty. He’d say, ‘Well, let’s go wash it off and start again.’ ”

A Black man of many firsts

The nation's first Black president, Barack Obama, also took great joy in fatherhood.

In his 2020 book, "A Promised Land," he described his reaction to the news that he would be a father:

"I was going to be a daddy," he wrote. "How full of joy the months that followed were! I lived up to every cliche of the expectant father: attending Lamaze classes, trying to figure out how to assemble a crib, reading the book 'What to Expect When You're Expecting' with pen in hand to underline key passages."

Obama was a state senator in Illinois when future first lady Michelle Obama gave birth to Malia Obama in 1998. He reveled in his role as a new father.

"A night owl by nature, I manned the late shift so Michelle could sleep, resting Malia on my thigh to read to her as she looked up with big questioning eyes, or dozing as she lay on my chest, a burp and good poop behind us, so warm and serene," Obama wrote. "I thought about the generations of men who had missed such moments, and I thought about my own father, whose absence had done more to shape me than the brief time I'd spent with him, and I realized that there was no place on earth I would rather be."

Berry said the contributions and sacrifices of Black fathers are often overlooked. They helped shape a nation even as they worked to mold their own children.

"If we want to pay homage to the perseverance of the American spirit, then we need to understand the history of Juneteenth and the fathers who forged a path for freedom’s progeny," he said.

Wayne Washington covers local government and issues of race for The Palm Beach Post. He is a husband, and father of two. wwashington@pbpost.com

No comments:

Post a Comment