Broward’s elections chief misled ethics commission about Scott’s sham blind trust

By Dan Christensen, FloridaBulldog.org

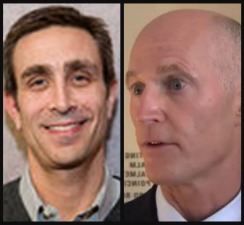

PETER ANTONACCI SWEARING IN DEC. 3 AS BROWARD SUPERVISOR OF ELECTIONS. PHOTO: WSVN7NEWS

Gov. Rick Scott’s newly appointed Broward elections boss was a staunch defender of Scott’s sham blind trust, and falsely told the Florida’s ethics commission five years ago that it was “modeled on” a federal blind trust.

Peter Antonacci, who replaced controversial elected supervisor Brenda Snipes, was Scott’s general counsel in August 2013 when he wrote to the commission seeking an opinion that would allow the governor to take advantage of a new state law authorizing so-called “qualified blind trusts.” The law, passed by a GOP-controlled Legislature and signed into law by Republican Scott, essentially provided immunity from prohibited or voting conflicts of interest regarding tens of millions of dollars in stocks, partnerships and other assets Scott held in his blind trust.

At the time, Scott already had a blind trust into which he had placed “substantially all of his financial assets,” Antonacci wrote in a letter co-signed by James T. Fuller, a tax attorney at the influential Washington, D.C. firm Williams & Connolly. Scott had established the blind trust a few months after taking office in January 2011, and now Antonacci was asking the ethics commission to confirm that it was in compliance with the new state law.

“That trust was modeled on the blind trust of the federal Office of Government Ethics, and on prior legislative proposals to recognize such trusts under Florida law,” Antonacci wrote. “The purpose of the trust arrangement was to preclude any appearance of a conflict of interest between the governor’s financial assets and his duties as governor.”

Scott, now Florida’s U.S. senator-elect, quickly obtained the eight-member commission’s blessing. The commissioners featured five Scott appointees, including attorney Linda Robison, the former Broward Health commissioner who is today awaiting trial with four other current and former hospital district commissioners and executives on criminal charges of violating Florida’s Government-in-the-Sunshine law.

Blind trust differences

In April 2014, Florida Bulldog reported that Scott’s blind trust deviated substantially from the federal model. In fact, Florida’s qualified blind trust law omits more than a dozen federal requirements intended “to assure true blindness.”

The starkest difference between the federal and state rules is in who is allowed to serve as a trustee of blind trust. Federal law requires trustees and their employees to be “independent of and unassociated with any interested party so that it cannot be controlled or influenced in the administration of the trust.”

GOV. RICK SCOTT, RIGHT, AND BLIND TRUST EXECUTIVE ALAN BAZAAR

Scott, however, chose Hollow Brook Wealth Management and its chief executive, Alan Bazaar, to manage his blind trust. Before announcing his first run for governor, Scott employed Bazaar for more than a decade as his managing director and portfolio manager at Scott’s eponymous investment firm, Richard L. Scott investments.

Federal laws and rules regulating blind trusts include additional safeguards not found in Florida’s statute. For example, federal rules make trust agreements and any amendments public records, but not in Florida. And federal public officials, their spouses or independent trustees or other fiduciaries who violate obligations under the law or the trust instrument face civil penalties of up to $10,000. Florida’s blind trust law imposes no penalties for violations.

At the time of the April 2014 story, Antonacci was asked about his letter to the ethics commission, why Florida’s blind trust statute does not include many of the federal level safeguards and whether those safeguards should be added to state law. He did not respond.

An ill-conceived assertion

Antonacci’s notion that the blind trust would “preclude any appearance of a conflict of interest between the governor’s financial assets and his duties as governor” soon proved to be ill-conceived.

PETER ANTONACCI

PHOTO: WSVN7NEWS

PHOTO: WSVN7NEWS

In March 2014, Florida Bulldog reportedhow Scott and his wife, Ann, had made more than $17 million selling hundreds of thousands of shares of Argan Inc. Those profits included the blind trust’s sale of nearly 141,000 Argan shares worth $2.5 million.

The blind trust was ineffective in blinding both Scott and the public to the specifics of his vast holdings. In this case, it was because of public reporting requirements at the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Scott owned so many Argan shares that he was required to report his Argan stock sales to the SEC. He even personally signed the reports.

Four months later, Florida Bulldog reported that Gov. Scott had a financial stake in Spectra Energy, the company that would build and operate the $3 billion Sabal Trail natural gas pipeline in North Florida. The story reported that in May and June 2013, Scott signed into law two bills designed to speed up permitting for the project, a controversial 474-mile pipeline from Alabama and Georgia south to a hub in Central Florida, south of Orlando.

In November 2013, the Florida Public Service Commission, whose five members were appointed by Scott, unanimously approved construction of Sabal Trail. Florida’s Department of Environmental Protection, overseen by the governor, also backed the pipeline by, among other things, awarding a crucial environmental permit to Sabal Trail Transmission LLC, a joint venture of Houston-based Spectra and Florida Power & Light parent NextEra Energy. Last year, Spectra merged with Canadian energy infrastructure company Enbridge.

Scott’s financial disclosure form filed six months later showed that as of the end of 2013 he owned more than $700,000 worth of units in Texas-based giant Energy Transfer Equity and related entities. Energy Transfer owned 50 percent of the Florida Gas Transmission pipeline, the state-regulated principal transporter of natural gas to Florida.

Conflicts of Interest

Conflicts of interest, real and apparent, rooted in the governor’s enormous portfolio have continued to emerge. In 2016, Florida Bulldog reported that Scott previously disclosed owning shares of Mosaic Company, owner of the Central Florida fertilizer plant where 215 million gallons of contaminated wastewater drained through a sinkhole into an aquifer that provides drinking water for millions of Floridians. The company has said it spent millions to seal the sinkhole, which was completed earlier this year, and installed monitoring wells and pumps to find and remove pollutants. The state monitored the spill.

In October, Florida Bulldog reported that Rick and Ann Scott have at least $5 million invested in Puerto Rico’s devastated electric company via their stake in AG Superfund, a New York hedge fund. That includes a blind trust investment of at least $1 million. Without disclosing the nature of his investment, Scott led a delegation of utility providers to Puerto Rico last year to help the hurricane-ravaged island.

The governor, via his blind trust, and his wife also had a huge, hidden financial stake in the Chinese railway company that supplied components to the U.S. contractor that built Brightline passenger trains for All Aboard Florida, a venture the governor strongly backed, Florida Bulldog reported in August.

The Scotts acquired their interest in Qingdao Victall Railway Group Ltd. in 2014 when it partnered with their company, Continental Structural Plastics, to form a 50-50 joint venture called CSP Victall (Tangshan) Structural Composites Co. Ltd. At the time, the Scotts were majority owners of Michigan-based Continental.

Continental was sold to the Japanese conglomerate Teijin for $825 million in January 2017. The sale produced a $200 million windfall for Gov. Scott personally, and another $350 million for his wife and 11 smaller investor-partners. Scott held his Continental investment in his blind trust and did not timely disclose his bonanza from the sale.

No comments:

Post a Comment