Our local governments, long run by dull Republicans and cognitive misers, don't protect the public interest. Case in point: sloppy arrangements with KINSA, which gets to use our data for profit.

Still no copy of any actual contract with KINSA, which is not legally qualified to do business in the State of Florida.

This is not the first time St. Augustine City Hall denizens have flirted with monopolists with Trojan Horse apps.

During the 450th anniversary of our City, this magical place, a City contractor's smartphone app for events had an unconscionable "take-it-or-leave-it" agreement, a "contract of adhesion," requiring that users agree to have their entire contact list, text messages and e-mails be accessible by the app vendor, GRAHAM MEDIA GROUP, owned by the family that once controlled the Washington Post.

After David Nails called it to my attention on Facebook, I raised the issue with Mayor Nancy Shaver, who said she never downloads apps from the internet.

Now, with Mayor Shaver out of the picture, City Manager JOHN PATRICK REGAN P.E. has embroiled the City of St. Augustine in a "partnership" with an incipient monopolist, KINSA, INC., which claims "over 90%" of the market for internet-based thermometers, with one million in American homes.

From Slate Magazine:

So About That Thermometer Data That Says Fevers Are on the Decline …

A smart thermometer company says its data could help track COVID-19. There are reasons to be skeptical.

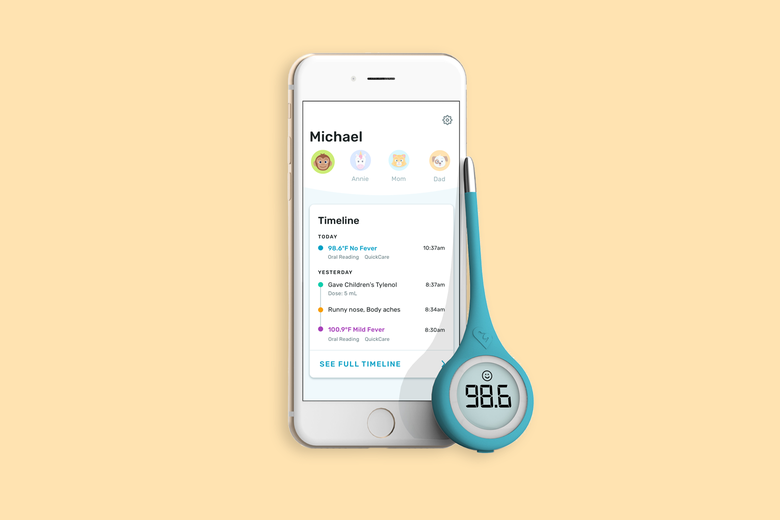

Photo illustration by Slate. Image via Kinsa.

This article is part of Privacy in the Pandemic, a new Future Tense series.

Now that much of the United States has been “sheltering in place” for weeks, it’s natural to wonder whether our collective efforts are working. Is the virus spreading more slowly as a result? It may seem like a straightforward question, but it’s hard to work out, because given the serious dearth of COVID-19 testing, data sets that rely on deaths or confirmed cases are incomplete—they leave out asymptomatic carriers and people who experience mild symptoms but aren’t eligible for testing.

Kinsa, a smart thermometer company, offers a side door to tracking the virus—or at least symptoms related to it. The company has a cache of users’ body temperature data, which it has begun to examine for trends. Based on this data, it announced Wednesday that it has seen a decreasing trend in atypical flulike temperatures across the country. To Kinsa’s credit, the company has included on its FAQ site the caveat that its map does not show COVID-19 infections. But in a blog post, the company’s founder, Inder Singh, made that logical leap anyway, saying that the results indicate social distancing is “working.” The goal, a Kinsa spokesperson told me, is not to paint a rosy picture of what’s happening in the U.S., but to identify signals that indicate abnormally high levels of fever in specific regions—and to show people some data that might motivate us to keep up the distancing.

Major news outlets like the New York Times, the Washington Post, and the Boston Globe have reported that Kinsa’s data demonstrates the spread of COVID might be slowing. One hopes this is the case, but there are also reasons to exercise caution in using and interpreting Kinsa’s data. First off, the metric Kinsa’s using—fewer fevers—might not be particularly meaningful for revealing coronavirus transmission. People with confirmed cases of COVID-19 have reported a range of symptoms; many don’t exhibit fevers at all. And while we’re all very focused on coronavirus at the moment, there are still plenty of other reasons people might develop a fever, like the flu. (A Kinsa spokesperson was clear about this as well.)

Even if Kinsa’s data set does reveal something about COVID-19, it represents a small sample of the U.S. According to the Times, at least 311 million Americans live in a state with stay-at-home measures in place; a Kinsa spokesperson told me they have sold or donated 1 million thermometers representing up to 2 million users, since each thermometer may be used between families. Even assuming every single user provided data used in Kinsa’s map andnone have opted out of sharing their data, that’s 0.6 percent of the stay-at-home population.That sample is also drawn from the pool of people who have bought this particular smart thermometer. Kinsa’s user demographics reported in a 2018 study suggest it’s skewed toward younger people, and uptake is higher in certain states, including California, Texas, and New York. In their paper, the company’s researchers report that readings “may not uniformly cover socioeconomic or age groups or geographic locations”; they specifically mention people over 50 as an “underrepresented population.” However, a Kinsa spokesperson told me that since that study was done, they’ve had more uptake from users older than 50, and that Kinsa’s current demographics reflect the general U.S. population, with more users in highly dense urban areas. (A blog post Kinsa recently released on their demographics shows that people 35–44 are overrepresented among Kinsa users as compared with the general population, while people 65 and over are underrepresented.) Still, it’s hard to know how well Kinsa users reflect the U.S.’s socioeconomic diversity; Kinsa’s cheapest thermometer is $35.99, a fair bit more expensive than your typical $5 drugstore thermometer. If wealthier, tech-savvy people in the U.S. are spiking fewer fevers, that might not tell us anything about national trends.In a moment when government officials, experts, and citizens are all hungry for data about COVID-19, Kinsa’s readings could help flesh out the bigger picture, as long as people understand the limitations. But even in a crisis, privacy matters, and sharing personal data—even in aggregate—should merit close scrutiny. Facebook and Google are now sharing aggregated user location data to assess people’s adherence to social distancing policies, and in other countries, like India and Israel, citizens are being closely surveilled. Anonymized temperature and location data may seem innocuous compared with the massive surveillance efforts that have taken off in the name of COVID, but health data is still a form of surveillance.

I talked with a Kinsa user who said she was aware that Kinsa could track fevers by state or region, but otherwise had “no idea” how else her family’s data was being used. In an effort to learn what Kinsa users agree to when they use the company’s service, I read over Kinsa’s privacy principles page, which lays out how its data is used, including sharing information with third parties and selling information to companies like Clorox to market their products. But that page made no mention of, say, creating a “U.S. Health Weather Map” with data broken down by county, accessible to anyone online. I attempted to access the privacy page linked from the company’s FAQs page but got an error message; I then also attempted to access the “additional legal details” linked on the bottom of Kinsa’s privacy policy page, but the link just redirected me to that same page. Luckily, a quick Google search did the trick, and the Kinsa app and website’s privacy policy appears to have been last updated in December. It, too, mentions personal info may be used for “business purposes” like marketing, or given to third party service providers, but none of the scenarios seem to account for a public map.

I asked a Kinsa spokesperson about how the Health Weather Map was rolled out, and whether users were specifically asked to opt in. She told me that users opt in to having their data used for things like the Health Weather Map, though there is an option to opt out of sharing data. The Kinsa user I spoke with didn’t remember opting in to this map or getting email communication about it, either. When we agree to terms and conditions for digital services—whether that’s Kinsa, Google Maps, or Facebook—we’re often agreeing to a blanket opt-in, where we’re offering to share our data with those companies for many uses, including new ones we never imagined as part of those terms and conditions we signed years ago. If Kinsa users were specifically asked to share their data for this Health Weather Map, would they have agreed? If Google Maps users had been allowed to opt in to have their locations tracked for their new “mobility reports,” which shows whether people are adhering to social distancing policies, would we have said yes?

Kinsa’s spokesperson also emphasized that the map’s data is anonymized and aggregated, with no way to pinpoint individuals. Location data collected and shared by Google and Facebook do the same. These are important precautions to take. But recent investigations have revealed that the individual records that constitute this aggregate data can be compromised, and even anonymized location data can be traced back to individuals with surprising accuracy. It’s clear that companies with access to user data want to help track the spread of COVID, and their contributions could be incredibly valuable.

Still, as researchers and companies rush to collect and analyze the data they have, users are left out of the discussion. How, exactly, will users’ data be used, and how useful is it to helping us understand COVID? And perhaps more importantly, what safeguards are there from preventing this data from backfiring on a community, or even individuals? As the pandemic rages on, it’s worth taking a step back and asking what data users are giving up in the name of COVID, and whether surveillance is worth it.

Future Tense is a partnership of Slate, New America, and Arizona State University that examines emerging technologies, public policy, and society.

No comments:

Post a Comment