Devastated that the actor Hal Holbrook, who played The Senator on NBC, has died. The Senator was my favorite tv show in junior high school, and influenced me to learn about and work for the Senate.

Hal Holbrook also played Mark Twain for some 50 years, and portrayed the FBI whistleblower, whom we now know was Mark Felt, FBI Assistant Director, in All The President's Men.

From tv historian Stephen Bowie's magnificent blog:

The Classic TV History Blog

Dispatches From the Vast Wasteland

The Senator: An Oral History

July 25, 2015

Last month, I wrote about The Senator, an Emmy-winning political drama broadcast during the 1970-71 season as part of the umbrella series The Bold Ones, for The A.V. Club. The Senator is about as old a television series as you can find where nearly all of the major creative personnel are still alive, and I was fortunate enough to interview most of them: producer David Levinson, associate producer/director John Badham, writer/director Jerrold Freedman, writer David W. Rintels, and editor Michael Economou. (I didn’t speak to the show’s star, Hal Holbrook, but the recent DVD set includes a terrific new half-hour interview in which a fiery Holbrook recounts his memories of the show.)

Because the vast majority of the material I gathered wouldn’t fit into the A.V. Club piece, I’ve compiled it here in the form of an oral history. It covers the standalone pilot film, A Clear and Present Danger; the development of the series; and then the individual episodes, at least half of which are little masterpieces from a period when quality television drama was scarce.

Jerrold Freedman: It probably got started with Jennings Lang, and Sid Sheinberg. Probably two thirds of NBC’s product came from us [Universal], and Jennings Lang was a great salesman. By the time we got going on these shows, he had moved on to the feature side. But he had been the guy who invented World Premiere and all these other things. It was a way to get a lot of different shows going with the idea that if one of them caught fire, they could make a regular series out of it. You could also do things and take chances with a six- or eight-episode series that you couldn’t do with a 24- or a 26-episode series. Bill Sackheim created The Protectors, the [Bold Ones] show I did.

Michael Economou: Bill Sackheim was a nice man. My kind of guy. He was very precise when he spoke. Great sense of humor.

Freedman: Bill was a guy who would create shows but he didn’t want to run them. He didn’t want to stay on for the series. Bill was really one of the greatest creator/writers in television. He was up there with Roy Huggins and Stirling Silliphant and guys like that. And he was also a mentor to a lot of us. He was a mentor to Levinson and me and Badham, and Joel Oliansky.

John Badham: I was working for the producer, William Sackheim. He and the writer, who I’m pretty sure was Howard Rodman, had developed a story called A Clear and Present Danger, before the Tom Clancy novel of the same name, and dealing with something that at the time some people said was ridiculous.

David Levinson: I forget the genesis of it. Someone had come in and proposed the idea. I think that [S. S.] Schweitzer came in and proposed the idea. A. J. Russell came in behind him, rewrote the story, wrote a script that was not very good, and they brought Howard [Rodman] in to write the script that ultimately became the pilot. I think it’s all Howard.

Badham: Why were we doing a story about air pollution? Because it was just not widely recognized as any kind of a problem, and yet Bill Sackheim and Howard Rodman had a strong belief that it was a serious problem, and they built it around the character of, I believe, a high level attorney in the Justice Department. That character was cast as Hal Holbrook, and as the story follows, [there are] some really serious air pollution attacks around cities of steel mills and big industrial sites, and the resulting waves of illnesses that came from it with people getting really sick and so on. The Holbrook character’s effort to bring law into this, and the difficulties, because as I said people didn’t regard this as a problem, and we were able to utilize that as part of the resistance in the program. You would think that the bad guy would be the air pollution, but it was the people surrounding it. To make a kind of silly comparison, the bad guy in Jaws could be either the shark or a silly, stupid mayor who doesn’t want to shut the town down because it might hurt tourism. The industrialists who owned a lot of these big industrial sites [were] saying, “Listen, hey, you’re going to shut us down? We’ll just move to China. We’ll just move to another state.” So that was the subject of it.

The director was James Goldstone, a wonderful, very creative director, who took the crew to Birmingham, Alabama, which I had recommended to them. I grew up in Birmingham and that was a heavy, heavy industrial steel-making city where the sky would be ablaze at night with the furnaces going. Very beautiful sight, but my father had terrible emphysema because of living his entire life in Birmingham. God knows how many people had been affected by it over time without really realizing what was going on. Goldstone shot in Birmingham for about a week, but as soon as U.S. Steel got wind of it, they started sending their security guys out to move us away from whatever sites we had picked, which probably had steel mills in the background. I don’t think we were ever on U.S. Steel property, but you could see these great furnaces going. They basically chased them off, and for a couple of days Goldstone drove around town shooting out of a van. Secret plates that he would use for backgrounds back in the studio, so that when they go to meet with the head of this fictitious company, in the windows behind him you could see these things going nuts and blazing away as he’s saying, “We’re not going to change anything other than move our steel mill to another city, and you guys are out of luck.” So the film was very, very strong, and really a good wake-up call.

In 1970, The Bold Ones added to The Senator to its roster, in place of The Protectors, for reasons that were never explained to its producer.

Freedman: Maybe the ratings weren’t as good as the other two shows it was with. I don’t know. One of the protagonists was black; I always wondered if that had anything to do with it. The other two shows were what, The [New] Doctors, and that stayed on for a while, and then the other one was The Lawyers, with Farentino? I think that those were more popular casts. We had Leslie Nielsen, who was a great actor but back then didn’t have the name power of some of these other people.

Levinson: I was given the show by Sid Sheinberg. Bill Sackheim was not able to produce a series. He had contractual obligations that prevented him from doing it, and he agreed to stay on if I became the producer. So it was his largesse that really got me the show. I had done a couple of seasons of The Virginian, and I had done one television movie. But basically this was going to be my trial under fire.

David W. Rintels: They had some very good people over there. Not only Bill Sackheim, who would fight for it, but a very good line producer, who really functioned on a lot of levels, David Levinson. They had pride in what they did, and Hal Holbrook had pride, and Michael Tolan.

Levinson: Sackheim rarely wrote anything himself. But his genius, and I’ve said this for years, was getting in really good people and then somehow drawing out of them the very best they had to offer. Any number of people I can name who were really successful writers and directors did their best work with Bill. He was my role model.

Badham: In all of the episodes, he was always there. More in the form of a consultant than anything. David Levinson was clearly the boss and the leader, but he always included Bill in script decisions and reading scripts and looking at cuts and getting Bill’s feedback and input.

Freedman: Universal turned out tons of great filmmakers, because they were really willing to give young guys a shot. We had Huggins, we had [Jack] Webb. It was a mixture. But they weren’t averse to young people, and most other studios were averse to young people. It was hard to get in as a young person, much different than today. I was the youngest producer in the business when I did The Protectors.

Economou: The thing that was very refreshing was that everybody was under thirty. They were young kids. David Levinson, David Rintels. There was such a heat, such a tremendous energy created.

Levinson: Stu Erwin, Jr. was the studio executive on it. But the truth of it the matter was that whenever we had a major problem with the show I went straight to Sid Sheinberg. I mean, he was the guy that had given me the show, and as he said to me once, would always afford me enough rope to hang myself. He ultimately was the boss.

Freedman: When Sid took over television from Jennings, which was either about ’67 or ’68, I don’t think Sid was more than 35 years old. Sid was a really combative guy. We used to fight like crazy. But he was really a stand-up guy for his people. He would say to me, “Whatever you’re doing, I’ll back you. You and I might fight but when it comes out to the rest of the world, I’m going to be right here behind you.” And he was. He really backed us. And we were doing shows that, in their time, were kind of revolutionary, whether it was The Senator or The Psychiatrist or some of these other shows. There was a lot of pushback from the network on those shows, and Sid was very aggressive about standing up for us.

Badham: NBC ordered eight episodes of it, thinking it would be a continuation of the U.S. attorney general, and in conversation subsequently with Hal Holbrook, he came in and then he said that he thought that his job should be a couple of levels up from that. That it should be a bigger level, like a United States senator, who would have more heft and so on. I myself was worried that it might be better if he had less heft. If everything was a struggle for him, it wouldn’t be quite as easy as it might be for a senator. But cooler heads prevailed, and that’s where they started writing.

Levinson: When they bought the show, Hays Stowe was not a senator. At one point we had proposed that we do the eight episodes as the legs of his campaign to get him elected. That was not met with great enthusiasm by NBC. So we just elected him and made him a senator.

Freedman: David hired writers, but he had his bible already set. He and Bill Sackheim had done that before the show ever went into production.

Levinson: It was a question of finding writers. We were very lucky in that regard. Joel Oliansky, who had previously been working in features, was brought to our attention, and wrote the show that won him an Emmy. Another man by the name of Leon Tokatyan, whom Bill and I had both known and worked with, who was a sensational writer, [wrote] two episodes. Fred Freiberger had worked on a show called Slattery’s People, which starred Richard Crenna as a California congressman. He had experience, and so we brought him in [as a story editor]. The Gray Fox, as he was called.

Freedman: They wanted to tell topical stories that were both political and somewhat idealistic. You could say The Senator was a precursor to a show like The West Wing.

Levinson: We had one terrific story that we could not get approved, about a man who was up for a State Department job who couldn’t get clearance from the FBI because he was a homosexual. They were afraid he was going to be blackmailed. The answer, of course, is for him simply to announce that he’s gay. The problem was, he was married with two teenage sons who had no idea of their father’s other life. Remember, this is 1970. The network finally said to us, “You can do this story if, when he makes a statement, he says he regrets being a homosexual.” We said, “We don’t really think that’s something we could say.” And so it got killed. I’m sorry we didn’t get to do it. Robert Collins [wrote the outline]. Oh, man, he was good. He did a rewrite on A Case of Rape, which was a TV movie I produced, and the goddamn Guild didn’t give him credit. And he saved the script. I mean, he made it sing. A couple of years later [William] Link and [Richard] Levinson did That Certain Summer, which also starred Hal Holbrook as a man coming out of the closet, so somewhere it all got taken care of.

Badham: We cast Michael Tolan to play his chief legislative aid, and brought along from the pilot the woman [Sharon Acker] who played his wife.

Levinson: We had gone to Washington to talk to some people. I think we talked to Birch Bayh, who was kind of a star at that point, because he had just knocked out two right-wing nominees for the Supreme Court, Haynsworth and Carswell. Which, by the way, ultimately let to the kind of [confirmation] battles that we see today. We talked to some old-time North Carolina senator who had a jug of bourbon in his office. We got a tour of the whole Congress from a member of the office of the secretary of the Senate, and I remember as we were walking around, I said to him – we had met with Bayh and had been very impressed with him – and I said, “What do you think Bayh’s chances are of getting the nomination?” He said, “Ain’t gonna happen.” I said, “Why not?” He said, “Wife.” And that was it; he wouldn’t say anything else. All I know is Birch Bayh never got the [presidential] nomination. It’s a very closed-up place down there. Or it was then. I think it still is. You’re a member of a club.

Badham: My job was to try to figure out where vacuums were going to be and help out wherever I could. What are the sets for tomorrow looking like, what are the people in wardrobe looking like? All those things that the director and the producer run out of time, they just can’t watch out for all of these things. And I had, also, a background in casting, so I was very involved in making sure that we had the right kind of people for the various roles. I had done some short commercial pieces for another pilot that we had made, and David Levinson said, “Well, come and work on this series as an associate producer, and we will let you direct episode number seven.” So that was great. That was going to be my first [television] episode to direct, and it was terrific because I got to work with the crew all during the first six episodes. They got to know me and I got to know them, and of course I’m studying up like crazy, watching every director. We had some very fine directors there.

Levinson: The directors we had, by and large, were very, very good. That was Badham’s first two times as a director, those last two episodes, and he pretty much knocked everybody’s socks off. Jerry was just terrific, I mean the energy that poured out of him. And the guy that did both the first and second episodes, and also did the Indian show, Daryl Duke, was as fine a director as I ever worked with in the fifty years that I did this stuff. He was just marvelous.

Freedman: Hal Holbrook had a sort of Gregory Peck quality, like in To Kill a Mockingbird. That kind of real integrity that comes out on screen. Hal’s a good guy.

Levinson: He kept staring at me. I finally said, “What’s up?” And he said, “I’ve got a son that’s not much younger than you are.” At which point I probably grew a beard. But as the scripts started coming in and he began to get a sense of what we were aiming for, we became close associates.

Badham: How do I find enough nice things to say about somebody you’re working with professionally like that? Somebody who has been so involved in the script in a good, positive way, and comes to the set really, really knowing what he’s going to do, and able to say enormous, enormous clumps of dialogue as though he was making them up on the spot – as though he was writing the dialogue as he went. Such a brilliant, naturalistic kind of talent, with a sense of timing that very few actors have. Working with him was a joy, because it allowed me to pay attention to actors who maybe needed a little more help, and I could pay attention to them, because I had Hal there, just solid as a rock.

Freedman: He would voice his opinion, for sure. He was the star of the show. The star of a show is the guy whose face is up on the screen, and he’s got to take care of himself. Hal had things he wanted to do and didn’t want to do as an actor while playing the senator, because he felt he had a certain handle on the character and he didn’t want to violate that character’s integrity. Which could be exasperating for a producer, but it’s really a good thing to have.

Badham: As I learned much later, Hal Holbrook had to approve me [as a director], and they never told me that. I’m glad. But when he accepted his Emmy award, he looked at me and then said, “I’m glad I said yes,” which is the first time that I knew I had to be approved by anyone other than David.

If The Senator’s story material was unusually forthright and literate for its time, its visual style may have been even more cutting edge: a kind of fluorescent-lit naturalism that strongly anticipated the look of major political films of the coming decade, like All the President’s Men and Dog Day Afternoon.

Levinson: We did some stuff that had never been done before, of which I am proud. The lighting that we used, which was very, very high-contrast, very natural lighting, had never been used on a television show before.

Badham: What was then known as the quote, Universal look, unquote, was kind of a flat lit, bright, sunny look to everything. Even the moodiest drama would be bright, flat lit, and sunny. You can look at almost any series made at Universal at that time, and that’s what you would see.

Levinson: There was no docudrama up to that point. We kinda sorta invented it, without giving it a name. We wanted it to seem as real as [it] possibly could. John and I ran all of Frederick Wiseman’s documentaries up to that time.

Badham: They were hard to get. I had to somehow track down Frederick Wiseman and ask if we could borrow the prints to look at. Everybody, like Jerry Freedman and myself, were all crowded into the projection room to study how did he get this, and how can we simulate this kind of documentary feeling? We were talking about the Maysles Brothers and Frederick Wiseman, as well as Haskell Wexler’s Medium Cool. These were pretty strong influences.

Levinson: Basically we looked for cameramen who knew how to do that kind of lighting, and we found Jack Marquette, who was just sensational. Not only was he great, he was faster than lightning. So we were able to get a lot of work done in a relatively short time.

Badham: We were trying to have it look like it was not lit, that it was just the natural light coming in through the windows, or maybe a lamp on a table. That’s what Jack Marquette was bringing to it. A very rough documentary kind of look. Jack went on to be the cinematographer on the first years of The Streets of San Francisco, which [duplicated] the look that he had created for The Senator.

Freedman: I did a fair amount of handheld and long lenses and stuff like that, which wasn’t done then. It was sort of a departure. A Hard Day’s Night was very revolutionary in the film business. It was shot as if it was a documentary, and I liked the concept of doing that. My idea was to make it look as if it was really happening right now.

Badham: I can remember the day that Hard Day’s Night was run at Universal. In the slower times of the year, they would run a film at noontime for all the casting people, and everybody else would get in too. I remember one day Hard Day’s Night came, and I had already seen it in the theaters and wanted to see it again. My boss was sitting right beside me [and] did not stop complaining from frame one to frame last, complaining about, “You can’t do this! This is terrible! You can see the lights!” And I’m going, to myself, not to him, “Are you nuts? This is so exciting and so wonderful to watch this kind of filmmaking, as opposed to the staid, plastic look that filmmaking had devolved into.”

Freedman: I think the influence was the times. Easy Rider had just come out, Altman was starting to direct. It was just a big change in moviemaking. I went to see Easy Riderwith this old-time director, Dick Irving. He was another one of my mentors. Sydney Pollack basically learned how to direct by watching him. He came out of the screening and looked at me and he said, “This changes everything.”

Badham: Good for Dick, that he saw that. Yes, there was definitely that feeling around. I mean, I know people that were weeping at the end of that film, and didn’t get over it for days. I had a secretary who was working for Bill Sackheim, who had gone to see it with her husband. She was just distraught over the film, it got to her so strongly.

The budget for an episode of The Senator was reported in the press as $200,000 per episode, a fairly high figure for an hour-long television show at that time.

Levinson: It was like two and a quarter. It was enough for what we wanted to do. His apartment, his office complex, and the Senate hearing room were our standing sets. And we would steal sets – we’d go into other sets and redress them as we needed. But we were only out [outdoors] a couple of days a show. We were basically an interior, dialogue-driven show, much like a stage play.

Badham: We always thought that, first of all, we should have no makeup on our actors. This was virtually heretical to say. Well, of course his wife is going to have some makeup on. That would look really weird, because women don’t go anywhere without makeup. But guys go everywhere without makeup [so] let’s not put any pancake on them. Let’s let their little skin flaws show. And let’s make sure that the wardrobe looks like it comes from off the rack and is not tailor-made. Let’s try to pick locations that have some grit to them. In [one] episode we’re in a trash dump, with bulldozers running around behind, and flies on Hal Holbrook’s face. Which was not planned, but God bless him, he let these flies go on his face and made no effort to wipe them away. It was just wonderfully raw, and that was always our look.

Levinson: And I don’t know whether you noticed or not: There is no music in the show. The pilot film had music. What Bill Goldenberg did, which was really cool, was he took a bunch of sound effects and ran them through a synthesizer, and that became the score for the show. When we took a look at the first episode, and it’s pretty much wall-to-wall talk – I mean, our line was that that our idea of an action scene was two people yelling at each other – we called Bill in and said, “We don’t see where the music could go. What about you? Do you see any place you could put music?” After we ran it, he said, “I can’t.” So we made the determination then and there that we were going to do the show without any score. And it worked out great.

Episode One: “To Taste of Death But Once” (September 13, 1970)

Teleplay by Joel Oliansky; Story by Preston Wood; Directed by Daryl Duke.

Levinson: We had some areas that we knew we wanted to go into. Remember, this was only a couple of years after the Kennedy/Martin Luther King assassinations, so we wanted to examine what it would be like for a public figure knowing that he could be in the rifle sights at any time, and how it affected him. And Joel just wrote the hell out of it.

Badham: There’s a fabulous performance in the first episode, that Daryl Duke directed, and that’s Gerald O’Loughlin, playing a cop who’s doing a bit of security. I mean, here’s a guy that made a character in just a couple of scenes with Holbrook, as they talk about something about the way the government works. And when he dies of a heart attack, it just kills you.

Episode Two: “The Day the Lion Died” (October 4, 1970)

Written by Leon Tokatyan; Directed by Daryl Duke.

Levinson: We did want to do senility in the Senate. I suppose, if you put me to the wall and said who does this [character, played by Will Geer] remind you of, he reminded me of Everett Dirksen, who was the senior Senator from Illinois back in the fifties and sixties. But he wasn’t modeled after Dirksen. It started, if you look at the last scene, with The Caine Mutiny Court-Martial. That was the seed of it. But in terms of who it was, just a kind of marvelous larger-than-life character that peopled the Senate then. That was my favorite episode.

Badham: Will Geer is probably the best performance of the whole series, as an old senator who’s not quite all there any more. A really, really brilliant performance.

Rintels: Leon Tokatyan wrote a wonderful script.

Levinson: Leon Tokatyan was certifiably insane. He was just crazy. When he finished the first draft of the Will Geer show, he dropped off the script at my house and said, “I’m leaving town now because I know if I stay here another day I’m going to be killed.” And meant it, and drove back up to Tiburon, where he lived. He’d come in on a weekend and sit in the office stark naked, writing. But the sweetest, most collaborative kind of guy. Just a lovely, lovely human being.

Episode Three: “Power Play” (November 1, 1970)

Written by Ernest Kinoy; Directed by Jerrold Freedman.

Levinson: The show with Burgess Meredith, about [Stowe] taking care of fences back home, was also a delight. We tried to keep it as human as possible. We weren’t looking to do a polemic. Ernest Kinoy got credit on that one. Ernest didn’t have much in the final script. Jerry and I [rewrote it]. This was a tough New York guy who made his bones writing for The Defenders, and not a whole lot of humor. And this particular episode needed to be dealt with with some humor, because the thing about politicians is that, at least then, they would stand on the floor of Congress and hurl epithets at one another and then repair to their offices and get drunk together. There was a lot more camaraderie then than there is now. And Ernie just didn’t get that.

Badham: One scene I recall was a group discussion in a room. Maybe there were twenty people in the room, and all throwing ideas around. And Jerry said, “Let’s not do normal setups, where we’ll set up on this person talking and then we’ll do a set up on this person, but we’ll have the cameraman come in and have him try to film this as it’s going on, which means he’s going to have be whipping his camera over to whoever’s talking.” Just like a real documentary cameraman would have to do, if he came into a situation where you’ve got one shot at it and you’d better get it all. I just remember that scene as really strong and powerful because of the energy of the actors and the energy of the camerawork.

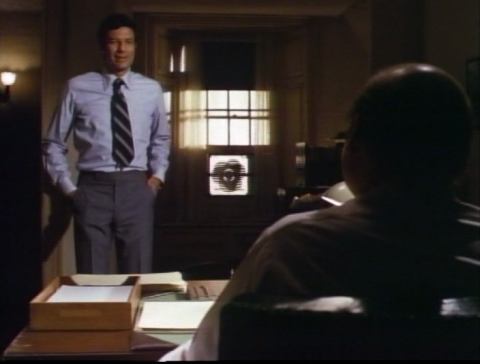

Freedman: It’s a [scene] of political activists giving Hal Holbrook hell. James McEachin was in it, and Michael C. Gwynne [above, far left]. I knew Jimmy, and Michael and I still are close. In fact, I gave Michael Gwynne his first acting job on the show that was Daryl Duke’s first directing job in America, which was an episode of The Protectors. Michael was a deejay, and a friend of mine said, “Hey, use Michael as an actor.” I said, “Yeah, let’s do it.” I don’t know if you noticed, but all of the young people like Michael and Holly [Near] are standing, and Hal is seated. Which puts him on the defensive. And do you know who the schoolteacher was in that show? It was Jack Fisk [below], who’s now one of the biggest art directors in the world. He had just come out from Philadelphia and he was good friends with a buddy of mine who was a very famous poet. My friend had said, “Hey, this guy’s coming out. Would you meet him and give him something?”

Episodes Four and Five: “A Continual Roar of Musketry,” Parts One and Two (November 22 and 29, 1970)

Written by David W. Rintels; Directed by Robert Day.

Levinson: Kent State happened, and David Rintels came running into the office and said, “I want to do a show about Kent State,” and we were all lathered up about the shootings, so we went ahead and did that.

Badham: The Kent State episode was really a brave thing to do, and a ripped from the headlines kind of thing. Everybody else was saying it’s too soon, it’s too soon, you can’t do an episode about that. But the writer, David Rintels, was just so gung ho. He came to David with the idea and said, “We can do it. We could make it a two-parter, and the senator could be doing a full examination of what went down.” It was a very exciting concept, and David Rintels wrote it in almost no time at all, because he was so passionate about it.

Rintels: I was working as a freelance writer and I got an appointment with Bill Sackheim. He was the person I went in and pitched to. Kent State had just happened a month or two earlier, and I had the idea of doing Kent State as Rashomon, and he liked it. But as I remember, there was an imminent Writers Guild strike. I think I might have gone in on the first of June, say, and the strike was called for June 15. We saw this as a two-parter, but he said, “You can’t possibly write that between now and the possible start date of this writers’ strike.” I said, “Well, let me try.” Because it’s not the sort of opportunity you got in those days, or maybe even later. That was a subject I cared a lot about, of course, and so I said I’d [do it]. I think I made it with at least ten minutes to spare. And I think they shot what was my first and last draft.

Badham: They almost canceled the episode.

Rintels: NBC’s legal department raised the question that if this show were broadcast in Ohio, that it could disrupt the Kent State trial. They were worried that somebody in Ohio would seek an injunction against the show being shown there. Well, Ohio is an important market for the network. We were worried about it. So I went to Hal Holbrook and we conjured up an idea that we would take out an insurance policy to indemnify the network. We didn’t think it was likely to happen, but if it did, we would take out a policy to protect them. We went in to Sid Sheinberg, who was a remarkable man, and told him what we were doing, and he said, “You don’t have to do it. We’ll do it.” NBC withdrew its objection, or maybe Universal, which really did support the show strongly, satisfied it. And there was no difficulty in Ohio.

Levinson: There was a lawyer at Universal who was in charge of the insurance that the studio carried against lawsuits. This guy was a right-winger who lived in Westwood, which was right near UCLA where the students were protesting all the time. He told us at one juncture that he slept with a gun under his pillow. He was damned if he was going to allow this kind of liberal trash to get on the air. And he was the final arbiter of all this.

Rintels: When I had my first meeting with Sackheim, I said, “Look, I won’t even start this thing unless we come to an agreement. This is my opinion, and this will be in the show. And if there’s going to be pressure or if I’m going to be [undermined], I just won’t start.” And he said, “That will be the ending of the show.” I remember I said to them, “You can try and force me to change mine, but instead of that, go out and hire a writer who believes that the students got what was coming to them to write a different show. But don’t make television be about nothing. Don’t let television always come to no conclusion, where everybody is equally at fault.”

Badham: The whole wrap-up by Hal Holbrook, we were forbidden to do, again by the lawyers at Universal. Hal Holbrook does a wrap-up – the committee findings. “And we found that the governor was negligent in this and that, and the head of the national guard messed this up,” and in polite, committee-type language he’s just going through and blasting all these people. Well, this was still a very live issue going on in the country at that time. I mean, nobody had been tried or anything happened to resolve what had gone down. So the lawyer said, “You can’t say this. You can’t say that the governor is guilty and we’re going to punish him. That’s just going to prejudice everybody, and you can’t do it.” This was a real dilemma, because we didn’t think you could do a two-hour episode without coming up with some kinds of conclusions.

Levinson: We went back and forth and back and forth, and finally in desperation we went to the head of the studio, Sid Sheinberg, who said, “Look, if you’ll do this and this and this to the script, I’ll get them to insure the show.” By that time we were so dug in. Remember, we’re all kids at this point, you know, we’re the rebel and he’s the establishment. We were going up against The Man, as it were. But when Sheinberg said, “If you do this and this and this, I’ll make sure it gets made,” by that juncture I was more than happy to make the changes. I can’t speak for Rintels. And we finally got it made.

Badham: David Levinson and David Rintels went up to the head lawyer at Universal and said, “What if we say all of this stuff and we think the governor was negligent, and then we add in the phrase, ‘…but this is an issue that will be decided in the courts.’ They looked and they said, “Oh, okay, you can say that.” So after every damning indictment, Hal Holbrook says – you’ve got the episode, so you can look at the language – “but this is an issue that can be decided in the courts.” The two guys walked out of there, they come back to the office, and they’re gleeful, because basically the language is non-prejudicial, but that is different from what you as an audience are hearing. What you’re hearing is, “The governor was negligent,” and then the rest is like those disclaimers that they put at the end of those pharmaceutical ads. “You could die from taking this stuff,” but you don’t hear it; you go, “This’ll cure my acne.”

Levinson: Those big crowd shots, we ended up buying stock footage from some people that shot film at the Berkeley protests. They were all wearing red arm bands, so we just put whatever extras we had in red arm bands and had those big shots of thousands of kids. I remember one of the other producers on the lot came up to me and said, “How did you get the studio to hire that many extras for you?” I said, “Stock footage, baby. We had fifty extras out there.” When you have no money, you get very, very inventive.

Rintels: I thought a lot of it was extremely well-done. There were a couple of things, inevitably, that I wish had been done differently or better. That was a tussle between me and the director. He wanted to make it more Rash and less mon, I dunno. It would have worked more effectively if they trusted the content and didn’t need to hype it, maybe. But I thought on balance they did a wonderful job. Hal Holbrook and Mike Tolan were really great. I was pleased. It was a good launching pad for me. It was the last episode of a series I ever did. I went on to movies and miniseries and theater, and I always think that that had a part in it.

Episode Six: “Someday They’ll Elect a President” (January 17, 1971)

Written by Leon Tokatyan; Directed by John M. Badham.

Levinson: Tokatyan came up with one about mafia involvement in big government, which was John Badham’s first episode.

Badham: The initial idea was kind of dealing with the growing phenomenon of lobbyists in Washington, and influence coming from all over the place. The title of the episode was “Someday They’ll Elect a President,” talking about lobbying groups and maybe in particular the Italian mafia. But that’s just kind of hinted at along the way. In the development of the story, the legislative aid, Michael Tolan, has had some connection with the Murray Hamilton character, and he’s got some weird connections, and as the Senate is calling a commission to look into undue influence, Michael Tolan feels he has some obligation to not throw his lobbyist friend under the bus. So he takes the fifth amendment in front of the committee and refuses to incriminate himself. The reaction was interesting at the studio. Sid Sheinberg promptly shut the show down and said, “We’re not making this script.” We go, “Why?” He said, “Well, you can’t have a lead character in a series take the fifth amendment, because when you do that, everybody knows that you’re basically guilty and you’re just evading.” We go, “No, no, no, it’s not that, it’s for an honest reason.” And he said, “I’m telling you, you can’t do that.”

Levinson: The studio rained down on us, saying, “He is not going to take the Fifth Amendment. He is not a communist!” We kept pointing out that the Fifth Amendment had been around longer than communism had, but that didn’t seem to matter.

Badham: So I’m now like a week away from shooting, and ready to slice my wrists. My one opportunity starting to flutter off in the breeze. And David Levinson and Leon Tokatyan put their heads together and came up with the following scene: Holbrook goes over to Michael Tolan’s apartment and says, “What are you going to say?” He says, “Well, I’m going to take the fifth amendment.” And Holbrook says to him, “If you do that, I have to fire you.” “What do you mean?” “Because everybody will think that you’re guilty.” He basically just puts out Sid’s argument. “Well, that’s not right, we have this constitutional right.” “I don’t care. Don’t talk to me about that stuff. That’s just irrelevant. We’ll find another way around it.” That seemed to satisfy Sid and the other lawyers at Universal who had taken great interest in this show.

Like many a young director making his debut, Badham filled his first episode with imaginative visual flourishes.

Badham: There was a journalist [played by Dana Elcar] that Michael Tolan goes to visit, and he had a basement apartment that we built as a set, but when you went to the exterior of it it was a brownstone street on our backlot, and you saw Michael Tolan go down underneath the steps to the basement level for the apartment. The idea of the scene was that when you walk into a dark room, your eyes haven’t adjusted yet, and it’s darker than a sonuvabitch. Over the course of a minute or so, your eyes adjust and you can see better. So that was the way Jack exposed it. He made it so it was too dark, way too dark, at the beginning, and then as the scene goes on, he’s just opening up the lens, bit by bit, so you start to see characters more clearly. And by the end of the scene you can see everything more clearly.

Economou: I always believe that the actor is the main connection to the audience, and the main carrier of the story. So I try to be as simple in dialogue editing as possible. That was my approach. As an editor, I tried to give it a narrative rhythm that was always moving forward.

Badham: There is one scene that had one big, big problem, which was a scene with an older senator, played by Kermit Murdock. Kermit was a wonderfully strange kind of man with an unusual voice, and kind of hefty, but some kind of gravitas that was really interesting about him. We all liked him a lot. And we get into what is a long scene for television, about a five- or six-page scene, which would take, at that time, about half a day’s work. Holbrook and Kermit are having what is an argument, but it’s one of those arguments that if you’re walking by in the hall, you would hear these guys talking and you wouldn’t know they were arguing. You know, grown, mature men having a discussion where they’re not yelling at one another. The scene was very leisurely, in spite of the fact that there was this good conflict built in the scene. And we go to dailies the next day, and David Levinson starts squirming in his seat. He’s talking to the editor and saying, “Can you speed this up? Can you speed this up? These guys are so slow!” And the editor, Michael Economou, said, “Well, I can take out the pauses in between their speeches. That’s easy. But I can’t make them talk faster.” So at the end of the thing, David looks at me and says, “We have to do this scene all over again.” Which was just devastating for me. On your first show, to have to do not a little scene, but a great big scene, all over again, because I had maybe been intimidated by the actors and intimidated by the fact that I liked them so much. This was the way they approached the scene, and I let them go. But I know enough not to throw the actors under the bus. I’m the director. I’m the one that should say, “Guys, we need to pick this pace up.” It’s not their fault. So it’s scheduled, and now my six-day show is going to become a seven-day show, which is unheard of at Universal. Nobody goes over. Sheinberg calls up David and says, “I hear you’re going over. What’s the problem?” David said, “Well, we just didn’t like a scene and we have to do it over again.” And I thought, boy, this is the end of my career. Before it’s even started, it’s going to be all over.

So we go back to the set on the seventh day, and Kermit and Hal start to warm up and rehearse the scene. They’re doing it about the same way, and I have explained to them why we’re back and why we’re redoing it, because we just need to pick up the energy and the pace of it. So after they’ve warmed up, Hal turns to me and he says, “Do you know, I love this scene. I just think it’s one of the best scenes ever. It’s just so beautifully constructed. And one of the things that’s really great about it is it has got this great leisurely pace to it.” And I went, oh, my God, we’re back in the toilet here. So I looked at Hal and I said, “Oh, Hal, I’m so glad you said that.” He looked surprised. I said, “We can actually go home. We don’t have to shoot today.” He said, “Why is that?” I said, “Because we already have that version!” [Laughs.] And he went, “Oh.” I said, “We need to really have these guys get in each other’s face,” or whatever the expression was at the time. So he said, “Oh, okay, all right.” Kermit, who would’ve done it naked, standing on his head if I’d asked him to, said, “Oh, okay, all right, let’s go.” So they did, and it was terrific. They really brought a lot of great energy to it, and it wasn’t just a leisurely afternoon conversation over drinks. The last time I recall seeing that episode, I thought, “Boy, this has turned out to be one of the best scenes in the whole episode, between these two guys.” So thank goodness it turned out pretty well.

Episode Seven: “George Washington Told a Lie” (February 7, 1971)

Teleplay by Joel Oliansky; Story by Bontche Schweig (a pseudonym for Ernest Kinoy); Directed by Daryl Duke.

Levinson: The Indian show is one of the worst pieces of casting I have ever participated in. We cast Reni Santoni, a nice New York Italian boy, as an Indian, and Louise Sorel as an Indian. And she’s a Jewish girl from New York. Man, did it look fake. They’re both good actors, by the way.

Badham (quoted in John W. Ravage’s Television: The Director’s Viewpoint[Westview Press, 1978]): [It] had to do with the building of a major dam on an Indian reservation. The Indians showed up at a senate hearing with picket signs and said that George Washington was a liar. “George Washington gave us a treaty,” they said. “We could be here as long as the grass shall grow, and the rains fall, etc. He has lied to us now.” The network looked at the script and said there was only one problem: We had to change the title; we couldn’t call this show “George Washington Is a Liar.” Why? Well, the network didn’t want to be caught saying that the father of our country was a liar.

We said, “Well, fellas, it’s not that he’s a liar, it’s that the present administration is not honoring the old treaties.” They said, “That’s the point. We can’t say that about our present administration. And, we can’t be casting aspersions on George Washington.” So we said, “Okay, well, what would you call it? Would you like to make some suggestions?” The head of programming said, “Yes, I have the perfect idea.” (He is an attorney.) He said, “I think you should call it ‘George Washington Told a Lie.'” There were blank faces all around the room. We hurriedly said okay and tried to stop and think about that one. Suddenly we realized we were dealing with a lawyer. And his logic was, very simply, that if you say George Washington is a liar you’re implying that everything he says is a lie. On the other hand, “George Washington Told a Lie” means that he told one lie. That’s not so bad. And suddenly, that made it all right …. It always amazes me that they didn’t see that we were saying the same thing. We had the title we wanted. It was just that strange little turn of phrasing that made everything okay. It made one lawyer believe that people would think just as logically as had he.

Episode Eight: “A Single Blow of a Sword” (February 28, 1971)

Written by Jerrold Freedman; Directed by John M. Badham.

Levinson: We we did one about welfare, and how the money was being spent in a lot of areas that took it away from the people that needed it. The whole episode, kinda-sorta, was based on what had happened with Jesse Jackson in Chicago, where Jackson was getting welfare money and distributing it to the Blackstone Rangers, which was a huge gang on the [South] Side of Chicago. In return for getting to use the money for whatever the gangs used it for, that’s in quotes, they were making sure that kids went to school and they were doing a lot of community activities. So that was vaguely what the Lincoln Kilpatrick character was based on. That was the last show we did.

Freedman: I was going to write and direct it. They needed a script, so I wrote a script quickly. It may have been that David gave me the storyline; I don’t recall. They liked it. David tweaked it a bit. Then for some reason they had to postpone production of it. I don’t know whether Hal got sick, or whatever it was. I was doing a pilot then and I had to go back east to research and I’d already set it up, so when they went past my window I wound up not being able to direct what was the last episode.

Badham: He was set to do this one, episode eight, and the story wasn’t firmed up yet, and time got really right, and he said, “I just can’t do this.” David said, “Well, okay.” Probably about an hour after that, I happened to wander into David’s office, and Holbrook is sitting in there, and I guess they were talking about what had just happened with Jerry Freedman. They looked up at me, and then I saw them look at each other, and they said, “Would you like to do this last show?” “Please, don’t even ask, where do I sign?”

Levinson: We couldn’t find young black men to play the roles. They just weren’t in SAG. And the reason was, other than Poitier and James Edwards, there just weren’t any black male [stars] around, so young men weren’t going into it. What Badham did was, he went down to the Watts Workshop, which had sprung up after the riots, and he found a bunch of these guys and brought them in and we wrote their SAG cards. By the way, SAG bitching the whole time: “Why can’t you hire actors we’ve got?” Well, because they’re all in their sixties and these guys were in their twenties. And some of those kids were just terrific.

Badham: There’s a scene that I did with [Holbrook] talking with one of his fellow senators, and they’re in the kitchen making a sandwich and arguing about sliced tomatoes. It was something that just developed during rehearsal, and it was just absolutely wonderful. They took a good scene and made it twice as good, just because of the life and the real interaction that they brought to it. The other actor, David Sheiner, was wonderful, and I had him in my film Blue Thunder as well. And I think Sheiner’s office actually was shot in David Levinson’s office, which was lit by fluorescents overhead. This was another kind of heretical thing to do. We would change out the fluorescents to things that were the proper color temperature for warm light. The daylight look that most fluorescents have, on film, tends to turn people’s faces turn green. We said, well, I don’t think we want to have Logan Ramsey and Hal Holbrook look green, but we do want to kind of get that kind of what it looks like to our eye before it goes on film, that very overbright, overlit government kind of look.

Levinson: What happened was – this is funny – we ended up with a very short script. We had told the story completely. There were no more scenes to play. And we came up with the idea of these man-on-the-street interviews, much like – I can’t remember if it was Truffaut or Godard had had witnesses in one of his films [probably Godard’s Masculin-Feminin, 1966].

Badham: An idea that David and I came up with together was, what if we had interviews with people on the street? Getting reaction from the mom in the parking lot putting her groceries in the car, or the guy working the lathe who got a job and is happy to be off welfare. I said, “Let’s do them with the real way these documentaries would be shot, which is with a sixteen millimeter camera, and we’ll handhold them and give them a special look, so they look different from the rest of our film.”

Levinson: Basically we wrote up a bunch of these interjections and we cast the actors without ever sending them the pages. On the day that they were to shoot, John gave them about ten minutes to just look over the page, and then he took it away from them. If you listen you can hear him very softly, off camera, asking him questions to cue them. So that the whole thing had a marvelous improvisatory quality to it. That was all Badham.

Badham: I said to the actors that we cast for these half a dozen [scenes], “I don’t want you to learn the lines that we’ve written, I want you to learn the sense of them. You’re just going to come in and talk about them, and say whatever you like, but you’re not stuck [with] these words, and I’d prefer you not be. I’d prefer you put them in your own words.” So we did, and the actors came up with just lovely little short bites, these little sound bites that were terrific. We could have added thirty minutes onto the show if we had used more of what they said.

Levinson: And the button on the thing, which was Hal on the talk show, and the cacophony of voices drowning him out, I thought was just perfect.

Badham: In the finishing and the editing of it, because we’re all editing on thirty-five millimeter, in order to cut these particular man-on-the-street interviews in, the lab made us quick temporary blow-ups of the sixteen millimeter. They blew them up to thirty-five and they gave us black-and-white copies. So we now are cutting black-and-white copies into a color picture, and as we refine the cut and get it in good shape, we really fall in love with these black-and-white images. So we said, “Forget the color. We’re going to stay with black-and-white here.” Everybody at the studio enthusiastically agreed, and it made it very special. Except for an interesting problem: We decided that the wrap-up to the episode was Hal Holbrook talking about this situation, but as a kind of man-on-the-street interview again. We had shot that in color, and now we had to make a black-and-white print of it. Today, that’s so easy: You push one button on the computer and, boing, you’ve got great black-and-white. At that time, if you tried to take color film and make it black-and-white, what you would get was something that was blue and white. Decidedly blue, and decidedly different. So the Technicolor labs had their work cut out for them for the longest time, trying to make this one thirty-second clip of Hal Holbrook look like the crappy, sixteen-millimeter, grainy stuff that we had created.

Levinson: When I went in to Sackheim and told him what we were planning on doing, John and I, he just looked [at me] and shook his head and said, “You guys are crazy.” But it worked out very well, I thought.

Over the first weekend of March 1971, the news broke that The Senator would not continue during the third season of The Bold Ones (which contracted to include only two, and finally just one, series over the next two years; as it turned out, the last and arguably best season of The New Doctors was produced by David Levinson). Two months later, The Senator swept the 23rd Emmy Awards.

Levinson: We had hopes that we were going to get renewed. The cancellation was very tough. They had been skittish about us all year, and our ratings were a little bit lower than the other two [Bold Ones series]. Not a lot, but enough to make a difference. So when it came it, wasn’t a total surprise. Didn’t make it hurt any less.

Badham: It seemed as though we were getting great recognition. We were getting tremendous feedback from senators in the United States senate, who were really appreciating the show, and our ratings were not bad for the time. I think we were getting 31% of the audience. If a show today got 31% of the audience, it would be a miracle. Nothing gets a 31. But at that time it was just on the ragged edge, and they didn’t go for it. Which was really surprising, and then to be followed up by the show having like nine Emmy nominations, and five of them were wins, as I recall. You thought, “Well, that’ll change their mind.” No. No, they had just moved on. And never looked back.

Levinson: I remember getting a call from one studio executive saying, “Listen, we don’t want to ruffle you any more than you’ve been ruffled, but your show is cancelled so we’re not going to spend any money promoting it for Emmy Awards.” I said, “Save your money. We don’t need your promotion.” They didn’t [promote the show], and we won five. The show itself won one; Hal Holbrook won one; Daryl Duke, the director, won one; Joel Oliansky won one; and an editor by the name of Michael Economou won for editing the Kent State show. In addition, Rintels was also nominated for his script, and John Badham was also nominated for that last episode. So we felt we were pretty well represented.

Economou: That was cool. I was an hour late getting to the Emmys, because my wife had bought an absolutely gorgeous dress, and she had a hard time [getting ready]. We finally sat down at the table, and the table was Hal Holbrook, the composer Pete Rugolo, and David [Levinson]. David had a sense of humor, and I had a very intense sense of humor, sometimes subterranean. So when I got up and I remember that I thanked the other four nominees, whose talented work I congratulated, and said I’m very lucky, that I want to thank the director, and then I said, “I’m getting to you, David, I’m getting to you.”

Although Levinson recalled that story development for a projected second season never advanced very far, Holbrook told reporters in 1971 that upcoming scripts would have dealt with army investigations of civilians, a presidential candidate based on George McGovern, the 26th Amendment (which lowered the voting age to 18), and the My Lai massacre (in an episode that David W. Rintels would write). The Emmy victory was enough to convince Universal to develop a follow-up TV movie featuring the Hayes Stowe character, if only as a face-saving gesture. Hal Holbrook and Rintels committed to the project, but the script – extraordinarily prescient in post-Patriot Act, post-Edward Snowden hindsight – was never filmed.

Rintels: It was a thrilling opportunity to get to bring it back. It was a script I loved, but the powers that be didn’t, and it didn’t go anywhere. I still regret it. It was based on the Senate campaign of Charles Goodell in New York, when the [Nixon] administration turned on him, and they beat him. Because he got interested in fighting the issue of government surveillance. The government was spying on people and he heard about things that were being proposed and being put in legislation that he went public with, and the administration got angry. This was all stuff that really was true then and is just as true now. The administration was interested in getting into people’s private communications. That was what it was about, and it was all fully documented. I gave the producers the whole list of [sources]. We were going to do it at least, or maybe at most, I can’t remember, as one two-hour movie. And then it didn’t happen. It broke my heart.

No comments:

Post a Comment