On July 18, 1978, the U.S.House of Representatives began discussing the issue.

My article was reprinted in the July 18 Congressional Record, instead by U.S. Rep. Joe Skubitz, a Kansas Republican, sans my reporting on campaign contributions.

On July 19, 1978, the House defeated coal slurry pipeline eminent domain legislation.

Three cheers!

A coalition of environmentalists, farmers, ranchers, libertarians, unions, railroads and good government advocates defeated Bechtel and other multinational construction companies, coal companies, electric power monopolies, the Who's Who of Houston, and deluded pseudo-liberals including Rep. Morris K. Udall and Rep. Bob Eckhart, beholden to corporate interests that employed Pat Jennings, former Clerk of the House, as their pipeline cartel's lobbyist.

Bechtel's Washington, D.C. pipeline lobbyist threatened me as I completed an 11,500 word article for Crossroads (formerly Coal Patrol): "If you write that article, you'll never work for the State Department, knowing I was a statement in the School of Foreign Service - Georgetown University. I responded, "ma'am, I don't want to work for the State Department." Within three years, both the Secretary of State and the Secretary of Defense were former Bechtel executives.

It was my first-ever published article; it was (minus campaign finance facts) published in the Congressional Record by Rep. Joe Skubitz (R-Kansas).

My late college roommate, Ed McElwain, had turned me on to coal slurry pipelines after researching them for Senator Gary Warren Hart.

Lessons learned: defeating multinational corporations is fun, environmental protection is everyone's job, investigative reporters really do have more fun, and there is nothing that you can't do in this great country if you put your heart, mind and soul into it.

A "technological turkey" was denied government favoritism -- eminent domain -- by the House of Representatives, which heard and heeded a diverse coalition. The environment, Wyoming water, farms, ranches, the Madison Formation, Wyoming, jobs and competition were protected from dangerous water-wasting pipelines using hexavalent chromium (the poison at issue in Erin Brockovich), which would have polluted Arkansas.

We, the People have"soul fire" as Ambassador Andrew Young puts it, of its opponents. They will win!

I am inspired by generations of activists, globally and locally, like the Nelmar Terrace and Fullerwood residents, who took on both a state agency (Florida School for the Deaf and Blind) AND a Japanese multinational corporation (7-Eleven), defeating FSDB on eminent domain and defeating 7-11's demands to build a gasoline station in our historic area at May & San Marco.

Venceremos!As LBJ said after Selma, "We SHALL overcome!"

more: http://cleanupcityofstaugustine.blogspot.com/2014/01/i-never-worked-for-state-department.html

Here's The Washington Post coverage of the story, the day before and the day after the vote:

Here's The Washington Post coverage of the story, the day before and the day after the vote:

Controversial Coal Slurry Bill in House

The House yesterday took up a little-publicized but intensely controversial bill that some say is an answer to the nation's energy problem and others say will simply start a new energy cartel.

The issue is the long-debated coal slurry pipeline, a new way of moving coal from mine to electrical generating station.

The legislation, on which the House is expected to vote today, could affect jobs, the use of precious water in the West, the health of railroads, electricity costs in some regions and, inescapably, the profits of a number of major corporations.

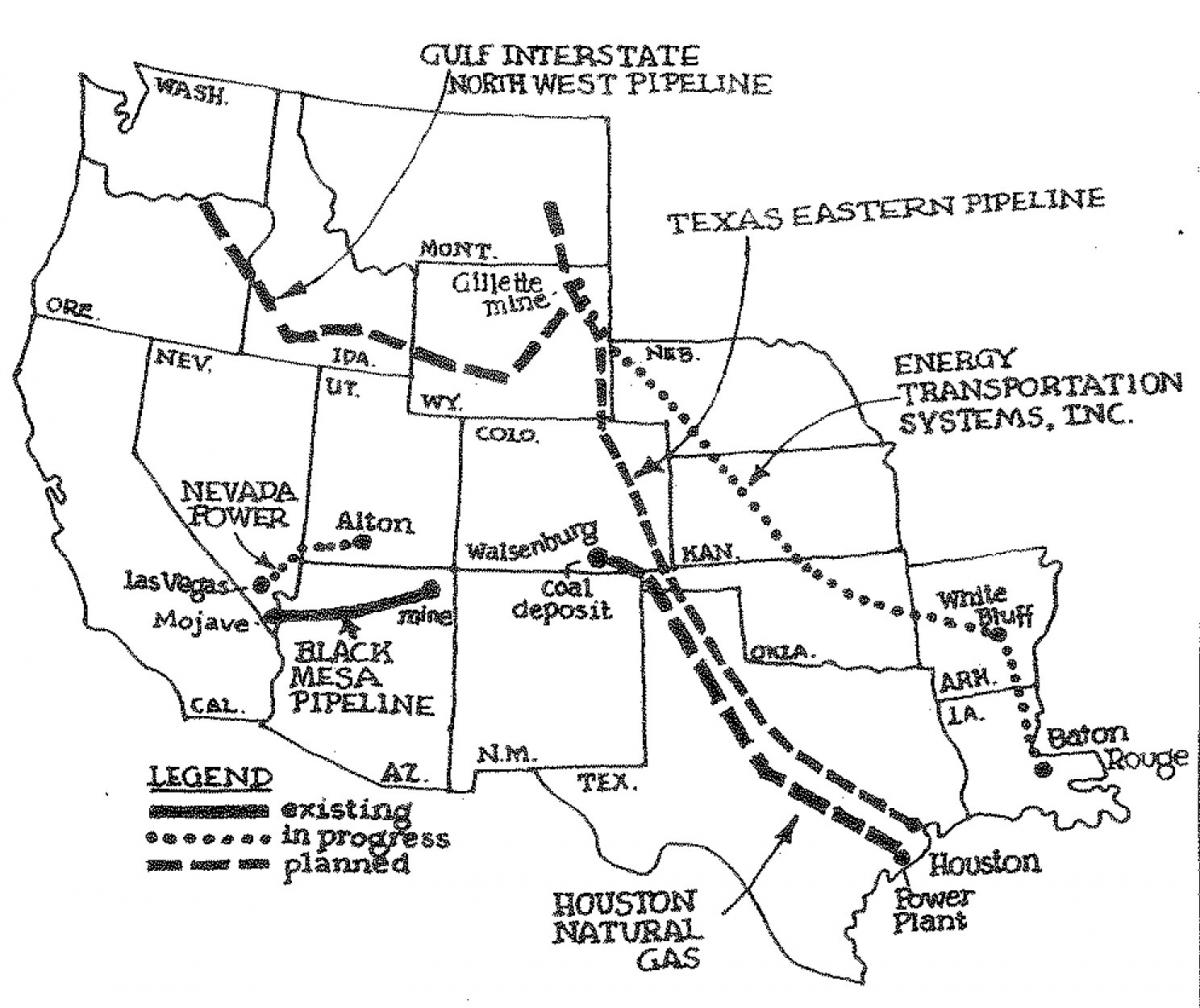

The legislation sanctions the construction of pipelines - some more than 1,400 miles long - carry slurried coal, a mixture of pulverized coal and water, to power plants.

To call the bill controversial is understatement. It pits railroads and environmentalists against pipeline interests and utilities, labor against labor and region against region.

It also pits House committee against House committee. The Interior and Public Works committees approved versions of the pending bill: Interstate and Foreign Commerce opposed it.

A key feature of the legislation would give the pipeline companies the power of eminent domain - allowing them condemnation power for rights-of-way across the property of railroads that also haul coal.

Railroads and railway labor groups have fought the legislation since it was first proposed in the early 1960s, on the ground that pipelines would undermine them and cost jobs.

Other opponents, led by Reps. Teno Roncalio (D-Wyo.), Ron Marlenee (R-Mont.) and Joe Skubitz (R-Kan.) charge that the legislation would lead to "an unwarranted raid on water already badly needed by farmers and ranchers" in the arid Western states.

They also contend that the bill inadequately protects the states in controlling allocation of water to the slurry pipelines, which need a ton of water for every ton of coal shipped to a power plant.

But the Interior Committee, asserting that the legislation would stimulate competition with railroads and benefit consumers, argues that coal slurry "may be crucial" in meeting national energy needs.

The battle over the future of coal slurry pipelines has created an unlikely alliance between environmentalists and the Association of American Railroads, which are opposing the bill for different reasons.

"We have no great love for the railroads - their coal-carrying unit trains create a lot of problems - but we fear that if you stimulate that competition, you'll be swapping one restraint of trade for another," said John Doyle of the Environmental Policy Center.

"We feel this legislation is going to create little coal slurry cartels in some regions of the country.They will own the coal, build the pipelines and control them, build the boilers for utilities."

In response to such criticism, the Interior and Public Works committees struck a compromise - they agreed that no single company could control more than 20 percent of a slurry pipeline.

Interior originally set the limit at 5 percent: Public Works, 35 per cent.

But other critics, such as Reps. James H. Weaver (D-Ore.) and Fred B. Rooney (D-Pa.), say the compromise doesn't go far enough - that it still would allow a few companies to control the slurry business.Critics cite the largest proposed pipeline system, a 1,000-mile span between a strip mine at Gillette, Wyo., and a new power plant at White Bluff, Ark., as an example of the cartel possibilities.

That project is the brainchild of Energy Transport Systems Inc. (ETSI), a combine made up of the B[e]chtel Corp. (pipeline builder), Lehman Brothers (investment house), Kansas-Nebraska Natural Gas Co., and United Energy Resources of Houston.

The pipeline they want to build would carry coal slurry from a Peabody Coal Co. operation at Gillette to a new Arkansas Power and Light Co. plant at White Bluff.

Arkansas Power is owned by Middle South Utilities Inc., a regional holding company. Peabody is partially controlled by Bechtel, the Boeing Co., the Williams companies and the Fluor Corp., each of which has interests in pipeline construction, power plant construction and hardware.

Middle South and Panhandle Eastern Pipeline Co. have entered into a long-term agreement with Peabody to produce coal at Gillette, where ETSI's pipeline would start.

Such an arrangement, the critics say, would lead away from competition. Railroads would be unable, even at lower hauling rates, to win contracts to carry Wyoming coal to the middle South, they say.

House Kills Coal Slurry Pipeline Bill

A surprisingly controversial bill to move Western coal to Southern and Eastern markets by means of slurry pipelines was killed by the House yesterday, 246 to 161, a victim of railroad clout and environmental fears.

When a bill has cleared two committees, as this one had, opponents usually have to settle for hitting it with a few weakening amendments. But in this case the opposition would up and killed it with one punch. That should be the end of the issue for this congress.

The Carter administration's energy plan envisions increased use of abundant coal in the future as an alternative to the oil and natural gas that the president and his advisers want to conserve. But a lot of U.S. coal is in the Far West, and one problem is how to move it to the plants where it would be burned in other regions of the country. Therefore, the administration backed the pipeline bill, though it was not a central part of President Carter's legislation.

Rep. Morris K. Udall (D-Ariz.), floor manager of the bill, said the action is typical of what the nation faces as it tries to evolve an energy policy and adjust to it. "Energy decisions will be tough, complex and tread on powerful interests," he said. "The result here was that the public interest got trampled."

A coal slurry pipeline would provide an alternative to railroad cars for moving coal from mine to market. Pulverized coal mixed with equal amounts of water could be pumped hundreds of miles, chiefly from Wyoming to power plants in the Texas-Arkansas area. The bill would, when the secretary of the interior decided it to be in the publci interest, give pipeline companies thep ower of eminent domain to obtain rights of way to building a pipeline.

Udall told the House that the sole purpose of the bill was to make available a new technology for moving coal. In most cases, he said, it would still be cheaper to move it by rail, but about 5 percent of the proposed doubled production by 1985 could be moved by pipeline.

He said the railroads would still get the bulk of new business from increased reliance on coal, that they need competition, and that the power to obtain rights of way has been given to gas and oil pipeline companies.

By opponents contended that it made no sense for the government to spend billions of dollars trying to make the railroads healthy and then turn around and create a competitor to take away their business.

Rep. Fred Rooney (D-Pa.), chairman of the subcommittee with jurisdiction over railroads, said slurry pipelines

In addition, some environmental groups opposed the bill for fear that the water mixed with the coal would become polluted and pose a disposal problem.

Another fear was the pipelines would use up the water of the arid Western states, even sucking up underground water from neighboring states not involved in the coal business.

Udall said he would accept the most absolute states' rights veto over use of their water that could be written. But a debate that lasted most of yesterday morning showed there was no agreement that this could be done.

After the bill was killed, Udall blamed the loss on the fact that only a few sections of the country stood to benefit in the foreseeable future, that railroad management and unions worked hard and effictively against the bill and that a few "knee-jerk" environmentalists saw a problem that wasn't there, and because of the "pervasive influence of the emotional issue of Western water."

No comments:

Post a Comment