Do proposed RV developments require greater scrutiny by St. Johns County Commission? You tell me. Watch St. Johns County Board of County Commissioners meeting non-agenda public comment and item 2 from meeting of August 19, 2025 -- Agenda Item 2 re: RV Campground Land Development regulations. Curiously, there's still no detailed backup material on this item. Only thirteen (13) words. As my grandmother would say, St. Johns County's GROWTH MANAGEMENT DIRECTOR MICHAEL ROBERSON is "typical of his type." As my mom would say, "we are surrounded by mediocrities"

From The Washington Post:.

Proposing an upgrade in an area known as “Flash Flood Alley,” developers assured city officials that guests would have time to flee.

Tran waved away concerns when a council member raised the issue of flooding. “We usually get about an hour or two heads up on flooding around here,” he said, according to a recording of the meeting obtained by The Washington Post. “I’m a poor man’s weatherman, so I’m watching it all the time.”

But when a catastrophic flood struck Central Texas in the early morning hours of July 4, sending the Guadalupe surging to record levels, at least 37 of those killed were staying at HTR TX Hill Country, according to interviews with victims’ relatives and friends. That would make the site the largest known cluster of deaths in the disaster, which officials have said claimed at least 137 lives.

The deadly force of the Guadalupe swept away motorized RVs and trailers the company billed as “tiny homes,” according to survivors’ accounts. Emergency responders reported hearing people call for help as they were swept down the river, trapped inside vehicles and trailers. Four of the dead at HTR were children, family members said, including a 5-year-old girl whose mother and grandparents were also killed.

A Post investigation found that, after downplaying the danger at the council meeting, HTR pursued an upgrade that kept RV sites in the Guadalupe’s “floodway,” a designation for areas that face such high risk from fast-moving water that some states and counties consider them too hazardous to build on. The company added the tiny homes, trailers that it said remained portable despite being outfitted with roofed porches and stairs.

Government officials also did not stand in the way. During the 2021 meeting, some city leaders said they welcomed the revenue the upgrade could bring — and, a person at the company said, the city later issued a floodplain permit to HTR. Federal guidelines allow RVs to be placed in floodplains as long as they are on-site for fewer than 180 consecutive days or are “fully licensed and ready for highway use.”

HTR and its partner in the project, Boston real estate firm the Davis Companies, said in a statement that the severity of the flooding on July 4 could not have been anticipated and that failures in public warning systems meant they had little advance notice. The companies said their communities were devastated by the tragedy and that their property manager’s actions that night “saved many lives.”

The companies said they are reviewing the approvals granted for work at the site and “are confident we are in compliance.”

“The HTR campground in Ingram existed for decades prior to our purchase in 2021, and our infrastructure improvements focused exclusively on modernizing outdated utility and sewer systems and decreasing the number of available sites on the property,” said ScottDeveau, a spokesman for the companies. “These improvements were welcomed by the community and approved by local officials, and they did not increase the RV sites’ proximity to the Guadalupe River.”

Through Deveau, Tran declined to comment.

In the aftermath of the flooding, much of the public scrutiny has focused on Camp Mystic, where 27 campers and counselors died. Less attention has been paid to the many RV parks in a valley known as “Flash Flood Alley.”

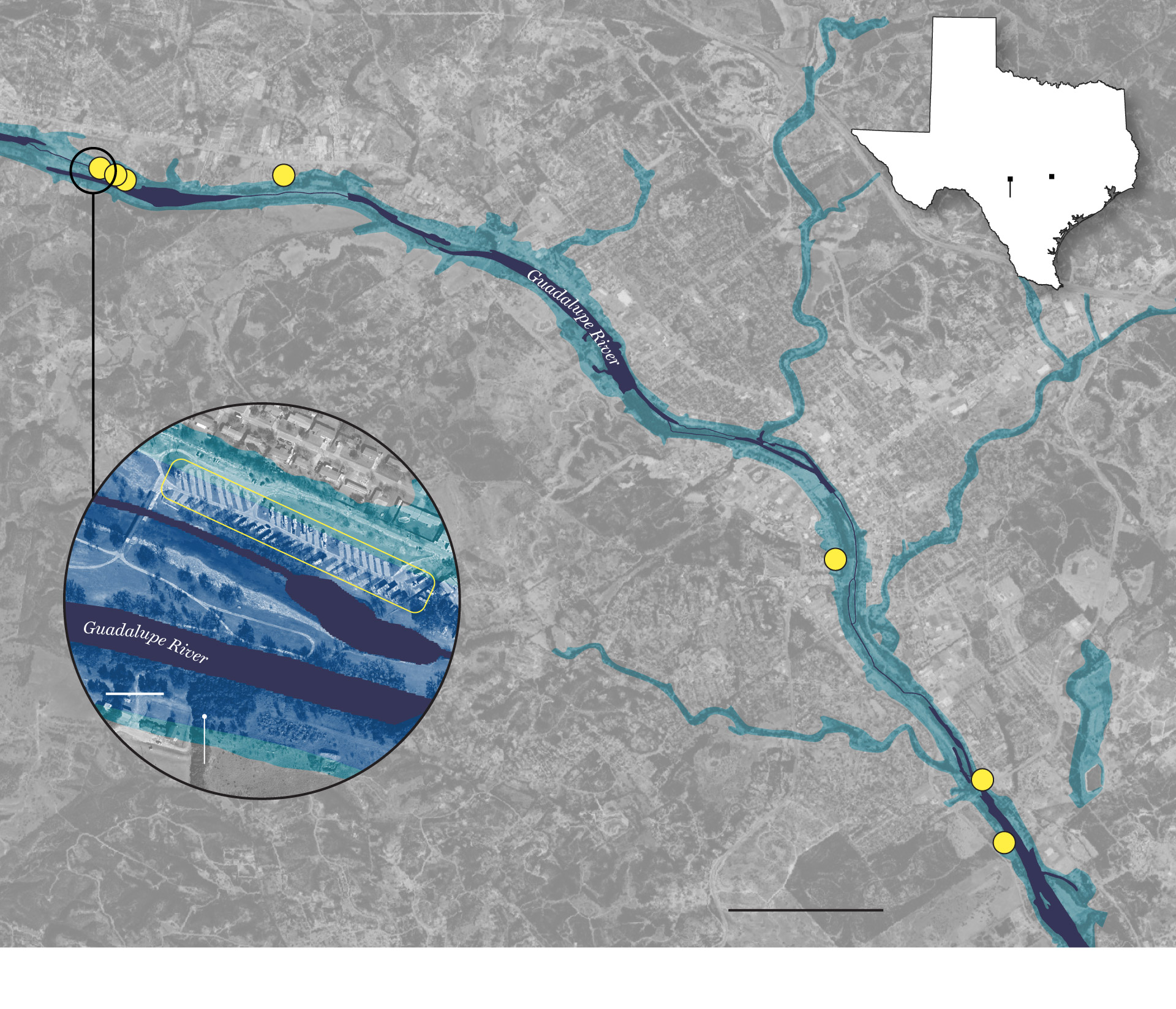

The Post found that 12 campgrounds in Kerr County, which includes Ingram, have RV lots located within the Guadalupe River’s high-risk floodplain, an area where there is at least a 1 percent chance of flooding each year, according to the Federal Emergency Management Agency. Seven of the campgrounds sit at least partly within the more dangerous floodway, including HTR — short for Hit the Road. On July 4, six of those in the floodway and four of the others experienced physical damage from the floods, ranging from trees being flattened to RVs being swept away, according to interviews with residents and a review of satellite imagery, local news reports, and photos and videos posted to social media.

Ingram

TEXAS

Damaged RV parks

Austin

Ingram

Kerrville

FEMA

high-risk

floodplain

Floodplain

Damaged area at

HTR RV park

200 FT.

KERR COUNTY

Floodway

1 MILE

The area in this map was selected to clearly depict the river and floodplain. Three RV parks that were damaged are outside the mapped area.

Image Credit: Google Earth

Today, little of HTR remains but flood-scoured banks. Gone are the tiny homes, the parking pads and RV hookups, swallowed by the raging river.

Stuart Gross, Ingram’s code enforcement officer and a retired sheriff’s deputy, said he is exploring ways for the city to prevent future RV parks from opening on land designated as a floodplain.

“It never should have been there,” Gross said of the HTR campground. “If anywhere along the line, common sense would have kicked in, we would have never had that loss of life, at least not this far down river.”

July 8, 2025

Nov. 14, 2024

RV parking

Tiny houses

Satellite imagery shows the damage to HTR RV park from the July 4 flood

Image Credit: Nearmap

Concerns about the campground that would later become HTR date back to at least 1989, when a developer, Robert Mobley, sought approval for what a local newspaper article described as a “recreational subdivision” in the river’s floodplain. Only two years had passed since a flood killed 10 teenagers from a church camp.

The article noted that Ingram officials “feared someone using the property could be trapped by unpredictable Guadalupe flood waters.” Officials ultimately approved Mobley’s RV park.

After Mobley died in 2021, his family sold the park to Davis and HTR.The Davis Companies has invested more than $12.8 billion in U.S. real estate and owns thousands of apartments as well as office buildings and hotels, according to its public statements.

Kathy Rider, who served from 2020 to 2022 as mayor of Ingram, a cityof fewer than 2,000, said Tran’s team met her in advance of the City Council hearing. Rider, who was 12 years old when the 1987 flood hit, said she told them about the risks of rising water.

“They said to me: ‘We have lots of rivers and parks on water, we know what we’re doing,’” she recalled. She told The Post she didn’t feel they were taking her concerns to heart. “I said, ‘You don’t understand, everything south of your campground office is going to wash away and be gone.’”

At the hearing, Tran said the revamped RV park would be a destination for people from Austin, San Antonio and other big cities as well as “snowbirds” — a prospect that Rider said would benefit the city, the recording shows. But first the park’s water, power, sewer and campground infrastructure needed to be upgraded and modernized, Tran said.

Tran told the council he was seeking a temporary exemption from a requirement that the RV park hook into the city sewer system, according to the recording.

One council member asked if the property was in the Guadalupe’s floodplain and was told it was. Rider said the city’s floodplain administrator would have to sign off on HTR’s development plans, adding that “RV sites are probably not going to be a real issue because they’re not permanent structures.” The council approved the sewervariance.

City officials declined repeated requests from The Post for documents related to the floodplain permit described by the person at HTR, who spoke on the condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to talk publicly. HTR did not provide proof of a permit. Multiple former and current Ingram officials said they did not know who the floodplain administrator was at the time.

Rider said the city periodically relied on a local engineer named John Hewitt to help with floodplain administration duties. Hewitt confirmed that he reviewed elements of the HTR plan in 2022 but said he was never told if a permit was ultimately granted. Current Ingram Mayor Claud B. Jordan Jr. said he did not know who, if anyone, holds the position now.

After Rider left office, her family held a get-together at HTR, where she said she approached the campground managers about her concerns over the tiny homes. Rider said she urged the managers to be prepared to quickly evacuate the campground’s guests. Rider’s husband, a first responder who has frequently raced down to the riverfront during heavy rains to pound on RV doors to get people out, spoke to the park’s management as well, she said.

“Their argument was, ‘Well, we have hitches on them and we can get them out quick,’” Rider recalled.

At the Blue Oak RV Park, the campground just downstream from HTR, the tiny homes also sparked concern. Gene Rhodes, who built Blue Oak on the site of a campground wiped out by the deadly flood in 1987, recalled watching several years ago as the HTR houses were towed into the park. It dawned on him then that a major flood could lift them and send them crashing into his property.

The houses “shouldn’t have been allowed,” said Rhodes, who sold Blue Oak in 2023. “It was going to wipe out 35 years of my work.”

Flood experts said the death toll at HTR is a reflection of the lack of attention most local and state governments have paid to RV campgrounds in flood-prone areas. The federal government leaves local jurisdictions to enact and enforce rules implementing the guidelines it sets.

“Regulation standards overwhelmingly focus on permanent buildings, and the Texas flooding shows campsites and RV parks are really an area of floodplain management that has not been given the attention it needed,” said Chad Berginnis, executive director of the Association of State Floodplain Managers, a nonprofit group that offers professional training and certifications. “For floodplain managers, what happened in Texas has to be viewed as an unacceptable loss of life.”

In 2006, FEMA published a floodplain training document advising that RV parks “should not be permitted in flash flood areas since there may be loss of life if flooding occurs as well as loss of the recreational vehicles.” FEMA has reprinted the 19-year-old recommendation in every training guide since, archived versions show, but it has never been required.

Kerr County is responsible for overseeing the floodplain in unincorporated areas, those outside the boundaries of cities like Ingram. Two years ago, the county rejected an effort to build a new RV park in an area under its control, said Charlie Hastings, the county engineer.

In Ingram, there appeared to be confusion about who held this responsibility, according to Hastings. He told The Post he has been contacted repeatedly about projects in Ingram by people who say they were referred to him by city officials. “I said, ‘Y’all need to get this fixed,’” Hastings said he told Ingram officials. “I was explicit. It’s outside our jurisdiction.”

On July 4, as the remnants of Tropical Storm Barry dumped months’ worth of rain, the Guadalupe rose more than 20 feet in a matter of hours. A wall of water bore down on the small strip of land occupied by three RV parks — HTR, Blue Oak and a third campground called River Run. In an area with spotty cell service and no warning sirens, the flash flood caught park owners and guests by surprise.

Lorena Guillén, who co-owns Blue Oak with her husband, Bob Canales, awoke to flashing lights from emergency vehicles. “I didn’t get a phone call. I didn’t get anything,” she said.

The couple’s RV park was a little more than half-full that night, with 28 reserved spots, most of them held by long-term residents. Seven day-trippers were camping on an island in the middle of the river, where the water was rising quickly. She said all but four people survived: a couple camping on the island and two of their children were killed.

As she and her husband raced door to door to warn campers to evacuate, they could hear tragedy unfolding at HTR.

HTR’s tiny houses were crashing into each other as the roiling brown river lifted them and carried them away, Guillén and Canales recalled. “They were hitting the other RVs and the cars. It started creating a cluster effect,” Guillén said. “All of that came toward us.”

The danger to RV campers was immediately clear to emergency responders, according to recordings of radio communications. Over more than an hour, firefighters began reporting the swollen river had claimed RV park visitors, including a family with children. Emergency responders reported hearing screams and watching vehicles and trailers being swept down the river with people trapped inside.

“We have children trapped in the water,” one emergency responder radioed at 4:35 a.m., asking a dispatcher to send help to what she described as “Howdy’s RV park,” an apparent reference to Blue Oak.

Sue and Lyle Glenna, the on-site caretakers at HTR that night, were asleep in their trailer when the fire department called at 4:45 a.m., their son Wes Glenna said in an interview. One minute later, a text alert went out to HTR guests, urging them to evacuate the park, according to a copy of the message obtained by The Post. The Glennas got into their trucks and began honking SOS signals — three short, three long, three short — to raise the alarm.

Soon, there were RVs in the current.

“We got an RV floating down the river with people in it right now,” an emergency worker said at 4:48 a.m. The RV hit a tree and split apart, according to a radio transmission a few minutes later.

Among others swept away by the river were Robert Leroy Brake Sr. and Joni Kay Brake of Abilene, who were staying in one of the tiny houses at HTR, said their adult son, Robert Brake Jr. He said he spoke with his dad at 4:44 a.m. to tell him that his brother and sister-in-law, who were staying at Blue Oak, had awoken with water rising in their RV, and that everyone needed to get out. When he called his father back moments later, there was no answer.

Brake Jr. said he worked in the RV industry for 23 years and understood the business but feared that campgrounds along the Guadalupe would be allowed to rebuild without new policies in place to protect people.

“They certainly wouldn’t let a developer come in and build houses down there,” he said. “Why are we letting people put RVs and tiny homes down there?”

Surveying the river from the patio of Howdy’s Bar & Chill recently, Canales said he and Guillén would rebuild Blue Oak. Their plans are still uncertain, he said, but he envisioned elevated cabins set back from the waterfront. There would be no RV park — no one bedding down in the floodplain.

“Even if it’s legal,” Canales said, “it’s still condemning people to an uncertain window of time when they could be washed out.”

Imogen Piper, Andrew Ba Tran, Alice Crites and Aaron Schaffercontributed to this report.

No comments:

Post a Comment