How the Democrats Took Back Michigan

Detroit—gretchen whitmer had her red water bottle with the Wonder Woman logo. Debbie Stabenow was touching up her makeup. Dana Nessel was up front, sitting with her wife, right behind the stack of boxed salads that was the food for the day.

The top of the Democratic ticket in Michigan—candidates for governor, Senate, and attorney general—were rolling along to the 77th and final stop of a statewide bus tour, hours before polls closed on Election Day. When the dust settled on 2016, no one would have been counting on any of them to be in contention, let alone win.

But with the way things were going now, two years later, they felt like singing. “We need a Democratic fight song we can all agree on,” Whitmer said.

Stabenow leaned forward in her seat. “This is my fight song,” she started to sing, moving her hands with each word of that song Hillary Clinton’s campaign had tried so hard to use to make her look cool.

“Nooooo!” a bunch of the aides shouted as they loaded up the speaker.

They went with Beyoncé, but only until Whitmer, heavily favored in the governor’s race, got her first pick: Lizzo’s “Good as Hell.” The younger aides were surprised she knew it.

“I do my hair toss,” Whitmer mouthed and tossed her hair, “check my nails,” and spread her fingers on both hands, looking down at the red polish.

2016 haunts Democrats here. 10,704 votes. The smallest margin of a Trump win, but more than that, a perfect picture of the collapse of a state stacked with all the unions and traditions and demographics that should make for a big blue unbreakable coalition: Trump got fewer votes than George W. Bush received when he lost Michigan to John Kerry in 2004, and Hillary Clinton got 43,000 fewer votes in Detroit than Barack Obama did four years earlier.

MORE STORIES

A new conventional wisdom took root: the white working class had abandoned Democrats, union leadership was decimated, and union members were peeling off to the GOP. Women couldn’t win. Progressives couldn’t win. African Americans, particularly younger ones, wouldn’t turn out to vote for anyone not named Obama. Change had caught up with the Democrats. Macomb County was gone. The Upper Peninsula was Trump country. The blue wall was broken and wasn’t coming back.

On election night in 2016, Whitmer was at home with her daughters, up late watching Clinton lose on TV. But what a difference two years can make. Now, in a few hours she’d be with them and the rest of her family and pretty much everyone she knew, standing on stage at the MotorCity Casino claiming one of the earliest wins of the midterms to become the new governor of the country’s 10th largest state.

Debate what counts as a blue wave in the rest of the country, but there was a tsunami off the Great Lakes. It was enormous and swept over everything: governor, Senate, attorney general, two flipped House seats with two female alumnae of the Obama administration, plus another that put a Palestinian American woman in John Conyers’s old spot, five flipped state Senate seats, five flipped state House seats, all the way down to the state supreme court and the state university boards. They legalized recreational pot, and the vote wasn’t close. They banned gerrymandering. They created automatic voter registration and an absentee-ballot process, essentially a backdoor way to institute early voting, which together will almost certainly lock in long-term the gains Democrats made.

Whitmer, a sexual-assault survivor, made “Fix the Damn Roads” her campaign slogan and talked about fighting health-insurance companies. She went up against a star of the Republican establishment who’d tried to wrap himself around Trump—and beat him by nine points in what two years ago had been expected to be the most expensive and bloodiest governor’s race in the country.

Garlin Gilchrist II, a 36-year-old African American, was elected lieutenant governor, the only male to win statewide. He’d come up through MoveOn.org and served as Detroit’s chief app builder but had never run before losing a city-clerk campaign in 2017. Senator Stabenow, who’s been in office since 1979 and seemed like a perfect target for Trump-inflected upheaval, never had to break much of a sweat to hold her seat against a black Republican former fighter pilot who had Trump surrogates pouring in for him through the final stretch. The new attorney general, Dana Nessel, is a lefty lesbian who led the lawsuit that overturned the state’s gay-marriage ban, and who launched her campaign last year with a video of her looking into the camera and asking, “Who can you trust most not to show you their penis in a professional setting? Is it the candidate who doesn’t have a penis?” The new secretary of state, Jocelyn Benson, was on the board of the Southern Poverty Law Center and wrote the book on best election practices for secretaries of state, winning a race she lost in 2010 and becoming the first Democrat in the job in 20 years.

All in the state where Ronna McDaniel ran the local Republican Party before moving to Washington to chair the Republican National Committee.

Mark Schauer, the former congressman who came close but lost in his 2014 Democratic campaign for governor, jokes that he has “cycle envy.” But he says he recognizes all that came together this year, including Whitmer out-raising an opponent who was kicking in some of his own fortune to a race that in total spending became one of the most expensive in Michigan history, to let her win on TV and on the ground.

“Donald Trump inspired a lot of people, and a lot of other things did too,” Schauer said. “That was not enough.”

Trump can win in 2020 without Michigan, but it won’t be easy. And winning in Michigan, based on the midterm results, doesn’t look easy. In 2016, this was his last stop—an after-midnight rally in Grand Rapids the night before the election where thousands waited for him and Mike Pence, giving him an inkling that maybe he might win. This year, despite pleas from local Republicans to come, he didn’t even try to compete. He hasn’t been in the state since April.

What changed?

“People didn’t feel inspired by the candidates, or they didn’t think that it mattered, so they were tuned out. The electorate hasn’t changed. But the fact that they’re really engaged is the biggest difference,” Whitmer told me, as the campaign bus rolled down the road. “It sounds too simplistic, maybe, but showing up is half the battle. People don’t want to be told what to care about. They want leaders who fight for what they do care about.”

First, michigan democrats had to figure out what it was that people cared about.

The Clinton campaign was a top-down disaster. Early on at the Brooklyn headquarters, they had come up with a model of who her likely voters were, and a plan based on the assumption that they wouldn’t be able to change the minds of anyone who wasn’t already with her, and that it was about turning out more of the people who were. Nervous for weeks of the final stretch, staffers on the ground begged for more help and attention. They were turned down, told not to worry.

“There was always a sense that we had this exciting opportunity to elect the first woman, she’s obviously so qualified and so smart, and look at this guy,” Stabenow told me, when we caught up at a campaign office in Madison Heights the day before the election. “So there were things that people let slide.”

The first calls Stabenow made on the morning of November 9, 2016, were to local doctors and nursing organizations, telling them to get worried and active on Obamacare. She helped plan the rallies around the country that Senate Democrats started doing, including what turned out to be the biggest one, featuring Bernie Sanders and Chuck Schumer, five days before Trump’s inauguration, with the crowd on the campus of Macomb Community College that had to be moved outside, into 28-degree weather.

Still, they weren’t sure that was actually going to win them any elections.

The Michigan State Democratic Party is based in a two-story house in Lansing. It’s cold in the winter and hot in the summer. The pipes freeze. Router wires hang from the bathroom ceiling. At the end of 2016, there wasn’t much cash left.

When Stabenow, already thinking of how to pull off a fourth term, showed up to meet with party leaders in January, they were already cutting the budget in search of $300,000 to cover the salaries of 10 field organizers at about $40,000 each. For the rest, they took a chance: hire the organizers, and make hosting small fund-raisers to pay their salaries part of the job. Stabenow cut a check for $150,000 from her campaign account for the very inventively titled Project 83—because it was about getting the party active again in all 83 Michigan counties.

In March, they brought the skeptical county chairs into a conference room in the Ramada West in Lansing to explain the plan. “Do something,” the party’s chief operating officer, Lavora Barnes, remembers telling them. “For some, it was a big something—run candidates all through 2017, and get them elected. For some, it was small—how about you just have a picnic?”

By April 2017, organizers were knocking on doors all over the state, earlier than the party had ever activated before. It had always waited to see who the candidates were, what went down in the primaries. It had always sent people out with a list of talking points to promote. This time, they were told to have a conversation, to find out what people were talking about. They weren’t sure they knew anymore.

Each organizer got a handheld device to input notes from the field remotely into the central voter database—devices the Clinton campaign had deemed too costly, opting instead for clipboards of pages of information that got taken down, but never entered anywhere. Organizers knocked on 180,000 doors, made another 20,000 calls, and got through to about 48,000 people. The answers that came back: Health care was far and away the top concern, followed by roads and infrastructure and the water in Flint, then education. Trump’s cuts to Great Lakes funding registered for some, as did Betsy DeVos, the education secretary vilified by Democrats across the country, but especially well known back home in Michigan.

Brandon Dillon, the state Democratic Party chair, met with the organizers behind potential ballot initiatives—eager from the outset for the push to legalize marijuana, with the sense that it would boost voter turnout, particularly on college campuses, which happened to be in some of the areas they needed the most help with. He and others at the party stayed in touch with some of the newly activated organizers, like the network of Indivisible groups that sprung up around the state.

They did not wait for advice on what to say or how to say it to arrive from Washington. They didn’t care, and they didn’t have to. Though the Democratic National Committee ended up putting about $700,000 into various Michigan efforts, from buying lists of 3.7 million new cellphone numbers to helping with outreach and dropping $337,000 into the state party’s combined campaign fund, Dillon put a massive $5 million in the bank over the cycle, expanding to 92 full-time organizers by Election Day (they’d planned on 80 to 85) and hiring social-media staffers specifically geared up to build an army of Twitter followers to amplify whatever the party or one of its endorsed candidates did.

“With big checks from outside groups comes the expectation of control,” Dillon said.

That’s what happened in 2016 and in previous cycles. It’s what very much did not happen in 2018.

“I think the results speak for themselves,” Dillon said.

Not everyone delivered. Officials in the state party were surprised, for example, to see several of the unions falling short of their promises, their leaders apparently themselves not realizing just how much the state’s right-to-work law had cut their ranks.

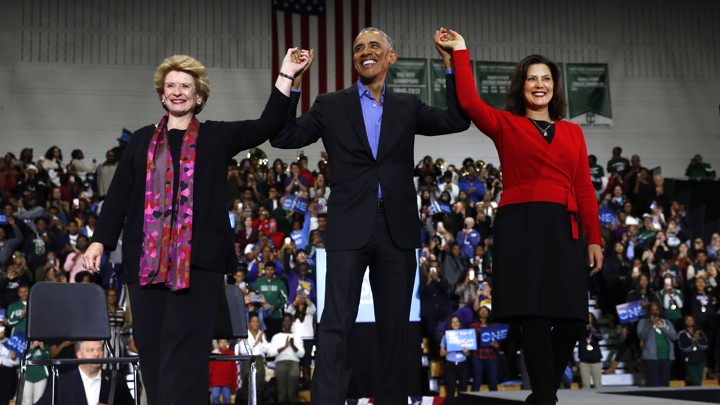

Stabenow, in addition to the $150,000 she spent out of her campaign account, came up with the idea of rebranding the state-party campaign the One Campaign, around a talking point that all the Democrats needed to be elected as a ticket, together, for the different roles they’d each have in pushing for the same goals. This manifested itself in resources and on paper.

Long before the primaries picked the nominees, the party decided to put every candidate on one piece of paper to be handed out at campaign stops and created a design: pictures of each of the statewide candidates, in the order decided by the state party, with room for only the names and not the photos of lower-level candidates. Local activists complained. State legislators said they thought they’d be lost in the shuffle when organizers were told to first pitch voters on voting for governor before working their way down the ballot. They were overruled, and on June 2, 2018, still almost three months before the primaries, the first door knocking started for what was now officially the One Campaign. Symbolically, they started in Detroit. They expanded to the rest of the state, and they didn’t stop until the polls were closed on November 6.

While this was all going on, Whitmer, a former state-senate Democratic leader with a tight midwestern accent and all the smoothness that comes from being insistently, constantly on message, was boxing out her biggest potential competitors, one by one. Everyone had expected Congressman Dan Kildee to run, but Whitmer announced in January, got herself to be the keynote speaker at the Women’s March in Lansing a few weeks later, and kept going from there. Worried, state Democrats cast around for other options—the freshman Senator Gary Peters was approached, and some held out hope through the beginning of 2018 that Detroit Mayor Mike Duggan would get in. People would whisper that Whitmer might remind too many people of Clinton, or of Jennifer Granholm, the governor from 2003 to 2011. (What they meant was: She is also a woman.)

When Whitmer’s campaign manager was dismissed for making unwelcome advances on women, her haters started to circle, and her fans began to worry she wouldn’t survive. Most concede that the reason she did survive was the scare her primary challenger put into her. His name was Abdul El-Sayed, a 30-year-old doctor who quit his job running the Detroit Health Department to run a very anti-corporate, pro–Bernie Sanders, youth-focused gubernatorial campaign. El-Sayed and the attention he started generating—could the next generation of Sanders-style politics work in the Midwest?—got her back up, pushing her all over the state.

He talked up a full ideological agenda. She kept talking about roads.

“The piece that really solidified it for me was, I was talking with a couple of moms,” Whitmer said. “And I said, ‘What are the most important issues to you?’ They both said variations of, ‘I just need you to fix the damn roads.’ Both had just gotten their cars out of the shop, they’d spent hundreds of dollars fixing their cars, it was money out of their rent or child care. It was the visceral reaction of both of them that really hit me. It is the clearest, most obvious glaring shortcoming of state government right now.”

They polled it eventually, anxious about being seen as vulgar, but they kept the “damn” in, a quiet, burning rage in a state where Detroit had gone bankrupt, the state government had covered up the poison in the water in Flint, and the paychecks weren’t getting better, even though the auto industry had been saved.

By the last few days of the election, staffers were wearing sweatshirts that read get out the damn vote.

Every senator comes off differently at home than in Washington, but the gap on Stabenow is one of the biggest. She doesn’t tweet. She doesn’t do much cable, and is more prone to talk about collaborating with Senator Pat Roberts of Kansas on the latest farm bill than she is to come up with a good Trump joke.

What Stabenow does do is quietly orchestrate state politics, in person, over the phone, and on the trail; she locks in on voters and refuses to let them go. By the end of the campaign, she was even joking that she’d gotten her tracker—the young Republican paid by the America Rising pac to follow her around with a video camera in the hopes of catching an embarrassing moment—to vote for her. Sure enough, when he saw her coming out of one of her last stops, he told her he was going to miss her and asked if he could give her a hug. (She said yes.)

Democrats in 2016 complained bitterly that Clinton never visited a United Auto Workers hall. Stabenow spent the Monday afternoon before the election in a parking lot outside an auto plant, catching the shift change, starting with telling the campaign workers where to stand with the handouts and stickers and ending with directing the setting and the script of the web video as the sun was setting and the last workers had come and gone.

etting ready to leave for Dearborn, Stabenow told me she was going to shake 600 hands there. Toward the end of the shift change, I asked her if she’d hit her handshake goal.

“Oh yeah,” she told me. “We’ll have to count the list. But at least.”

An aide followed up later. They’d counted: 1,500 glossy pieces of paper, each with every name and face on the ticket on it.

Later that night, Congresswoman Debbie Dingell listened as Stabenow told the University of Michigan College Democrats about her two hours in the parking lot.

Dingell loves that people call her Debbie Downer, and she tends to point that out as often as she reminds people that she’d spent the last month of the 2016 election warning that Trump could win.

She’d just come from a plant herself, down in Flat Rock, south of Detroit and near the Ohio border. Some workers saw her and started clapping along as they chanted “Trump! Trump! Trump!”

“The mood is still there,” Dingell said. “It could go either way.”

the downfall of bill schuette, Michigan’s Republican attorney general, started in Pennsylvania in 2014.

Staring down another late-breaking Democratic primary for governor that year, a group of consultants and activists came together and decided they weren’t going to wait for the results. They started raising money to pay for polls and research on Tom Corbett, the incumbent Republican who went on to be the only GOP governor who went down in 2014.

The staff at Progress Michigan took notes. They’d raised a few hundred thousand dollars in the 2016 cycle, but with national donors suddenly interested in Michigan, they’d begun amassing what would be a million dollars of independent expenditure money. By the end of June 2017, that was enough to start testing how to attack Schuette, the attorney general and longtime fixture of the Michigan GOP.

They started in Southfield, at an office building, with a group of women, mostly white, heavily middle-aged. They showed pictures of Schuette on the job, with his family, on his own, with other politicians.

“He looks kind of shady,” one woman said.

They started testing “Shady Schuette” on the five remaining focus groups. It stuck. Soon the phrase was in digital ads, which they were targeting by IP addresses, watching for who was at certain events, then popping up on their home computers. It chased him everywhere, even onto the stage of the Republican primary debate, with one of his opponents calling him that to his face, and another, the sitting lieutenant governor, launching a whole TV and web campaign around shadyschuette.com.

"For your opponents to pick up your messaging and put millions in ads behind it is like jujitsu,” said Patrick Schuh, the Michigan state director of America Votes, which also joined the effort, along with the League of Conservation Voters and the union- and Tom Steyer-backed group For Our Future.

They did market tests, matching the messages around “Shady Schuette” to psychometric clusters they’d assembled, seeing what kind of gun-control argument worked on people focused on education, or what kind of education argument worked on people focused on economics. That took up a lot of the money, and kept them out of the field for longer than they wanted—but by July 2017, the consortium of independent groups started knocking on what would be 3 million doors, with people responding at more than 500,000 of them.

The Service Employees International Union (SEIU) landed in Michigan with its own independent expenditure effort, shocked by the 2016 drop-off in working-class voters of color that they saw in the turnout numbers in Detroit, Flint, and Saginaw. At the direction of the union president, Mary Kay Henry, a Wayne County native, party strategists tore apart the formula they had been using. They stopped assuming that members were likely to vote and now assumed that they weren’t. Members knocked on 700,000 doors, changing that formula, too, now hitting up any home and not just the ones that the voter file told them were full of regular voters. That lowered their success rate, and a union spokeswoman said that it led to about 56,000 conversations. Members also sent 500,000 texts.

Between the state party, Progress Michigan, and SEIU, volunteers were knocking on a lot of doors, and many of them multiple times. This wasn’t always helping: By the summer of 2018, reports started coming back that they could see people inside who were refusing to answer, tired of being pitched by yet another eager volunteer with a clipboard.

Then the state party let Detroit Mayor Mike Duggan do whatever the hell he wanted.

Duggan fought with the Clinton campaign all through 2016. He’d been elected mayor in 2013 as a write-in candidate and had quickly consolidated a machine amid an old Democratic power structure that had gotten decrepit or indicted. He likes to be listened to, and he doesn’t react well when people don’t. Two years ago, he threw his hands up and walked away when the Clinton top command told him they’d handle Detroit. This year, furious about a no-fault car-insurance bill that was defeated in the state capitol, he backed 13 candidates in state-legislature primaries with a pac he had created that was backed by business interests. He won in eight races.

When Duggan told the state he wanted control of Detroit for 2018, Dillon, the state party chair, said yes right away. He had enough else on his plate.

Duggan, who prefers to work his political operation without getting into the sights of the outgoing Republican administration in the state or the ongoing one in the White House, declined to comment for this article. But his hand was visible all over the city. There were the bill schuette, hands off my healthcare billboards, and the rallies in the parks, and the targeted videos, and the carefully organized campaign offices.

In Livernois on Election Day, Duggan spoke briefly, introducing Whitmer, Stabenow, Gilchrist, and Nessel. He reminded whoever was listening of the promise he’d made at the outset to add 40,000 votes to the Detroit total from 2014, and to get to 200,000 votes. In the end, it hit 194,260, at 41 percent of the city’s registered voters (50,000 under the 2016 turnout, but a big jump for a state-race year).

What no one thought made much of a difference: the vote.org billboards, boosted by Taylor Swift’s money and endorsement on Instagram, that just encouraged people to show up at the polls on November 6. At one point, one of the more experienced operatives on the ground called the group’s offices to see if they’d consider adding to the sign a note about the hours the polls were open, or any information about how to get there.

The response? “Silence on the other end of the line,” the annoyed operative said.

By election day, most people had forgotten about Michigan. The races weren’t competitive, and there certainly weren’t any recounts, so interests and headlines moved on. But for a weird period of the spring and summer, El-Sayed’s bus was the hottest ticket in the country for political reporters chasing the next chapter of the Democrats’ veer left and the Sanders-Clinton civil war that would never end.

Sanders came to endorse El-Sayed. So did Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, two weeks after her own shocker takedown of the establishment.

For all the national coverage, it wasn’t much of a race: Whitmer beat him by 22 percent, a 200,000-vote margin. Then a funny thing happened: Onstage giving his concession speech, El-Sayed said he’d do whatever he could to support her, immediately pulling the air out of any ongoing protest.

“All of us learned the lesson of 2016,” El-Sayed told me, when we spoke on Election Day.

The Clinton-Sanders rift turned out not to be a real factor. Nor was the mass of Sanders voters, even in a state where the Vermont senator had beat Clinton in March 2016. Nor was the danger of having a primary overall.

I asked El-Sayed what he’d done over the final three months of the campaign to live up to his promise of doing all he could do. He pointed to several rallies for Whitmer, speaking at town halls in favor of her, making calls to supporters, and fund-raising for her off his list. He started a pac, Southpaw Michigan, which he said purposefully didn’t endorse in the governor or Senate races in order to keep the focus on the down-ballot campaigns it was backing.

El-Sayed isn’t over his opposition to Whitmer, still making claims of dark money from the state party that was secretly backing her.

“We’ve shown that despite our ideological differences and disagreements, we can show up and win elections on Election Day,” he said, professing peace before turning back to war in the very next sentence: “That being said, a lot of the questions about the soul of where the Democratic Party is going are still open questions.”

He took one more swing at Whitmer’s “Fix the Damn Roads.”

“She is running on a tagline of broken concrete when there are a lot of folks who can’t afford transportation,” El-Sayed said, calling it “a failure to appreciate exactly what is wrong with the approach to the challenges of working people.”

El-Sayed did a teasing Twitter poll asking if he should run for state party chair next year, but he says now that he won’t do it. Chatter is going around the state that he’ll run a primary to the left of Senator Gary Peters, who’s up for reelection in 2020, but El-Sayed told me that he’d told Peters directly that he wouldn’t challenge him. Then he hedged, retreating to calling a primary “highly unlikely” and saying, “I’m not intending to primary Gary.”

None of this goes over well with state Democrats, who are partying about the results but not at all confident that they’ll be able to keep their success going in the heat of a presidential election, as much as they seem to have landed on a formula for turning out city residents and minority voters in Wayne County and voters in the richer white suburbs in Oakland County, as well as making inroads to the blue-collar voters in Macomb County.

Dillon, the state chair, wants people to pay attention to what they pulled off, but warned Democrats in Washington, including whoever will be running the 2020 nominee’s campaign, not to assume it’s all taken care of.

“Do not overinterpret the results,” Dillon said. “It does not mean that voters are in love with us. It means we had a better message this time. That doesn’t mean we can’t screw it up.”

We want to hear what you think about this article. Submit a letter to the editor or write to letters@theatlantic.com.

EDWARD-ISAAC DOVERE is a staff writer at The Atlantic. He was previously chief Washington correspondent at Politico.

No comments:

Post a Comment