RONALD DION DeSANTIS, Florida Governor, links money with access and appointments.

His political committee planned to link in-person meetings, golf games and dinners to contributions, as the Tampa Bay Times reports. Orlando Sentinel columnist Scott Maxwell commented, "I imagine sex workers have similar rate structures." That's a subtle way of calling the Boy Governor a whore.

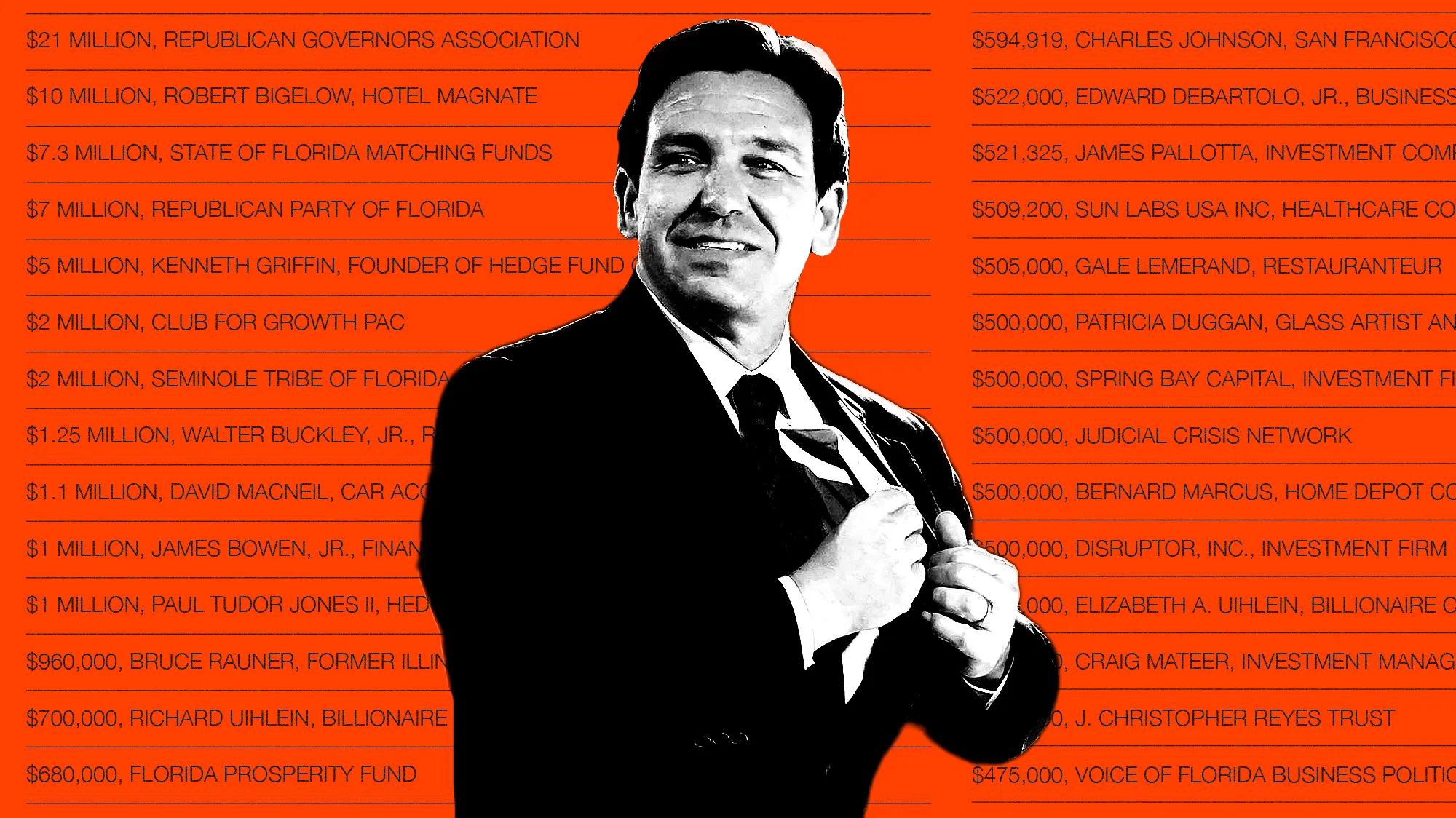

And in this story from the Herald-Tribune, below the photo, his appointments are of major donors.

Claiming to be a religious Roman Catholic, Florida Republican Governor RONALDS DeSANTIS stiffs the poor, refusing to block efforts to hurt affordable housing, while refusing to help efforts to expand Medicaid and seeking to inflict a poll tax on the poor who have served their time for felonies.

Sinister fellow.

We in St. Augustine and St. Johns County barely got to know this phony hobbledehoy in our employ since he was elected to Congress in 2012, an alien implant from the Koch Brothers. DeSantis treated one local official rudely, bailing on a scheduled appointment and breezing past him in his House office, presumably on his way to one of his more than 40 faux Fox News appearances, which attracted the endorsement of fellow phony DONALD JOHN TRUMP.

As they say in East Tennessee, Flori-DUH's Governor RONALD DION DeSANTIS "bears watching'." He rather reminds me of Tennessee Governor LEONARD RAY BLANTON, convicted of selling liquor licenses, who issued paid pardons to murderers and was removed early, with Lamar Alexander sworn in as Governor on January 18, 1979 (I was in the Nashville Tennessean newsroom that day, as a Georgetown University undergraduate investigating TVA coal procurement criminality on a Fund for Investigative Journalism grant). Watch this guy.

In United States v. Blanton, 700 F. 2d 298 (6th Cir. 1983), 719 F.2d 815 (6th Cir.1983)(en banc) cert. denied, 465 U.S. 1099, 104 S.Ct. 1592, 80 L.Ed.2d 125 (1984). \Governor LEONARD RAY BLANTON, corrupt Democratic Governor of the State of Tennessee, and his staff, were held to account for selling liquor licenses.

In the words of Patrick Henry in the Virginia House of Burgesses in 1765, RONALD DION DeSANTIS "can profit by their example."

Any self-respecting FBI agent would seek torun an undercover op on DeSantis under RICO and Hobbs Act.

Harrumph to this hypocrite!

Since it is Sunday, here's some Bible quotes for this double-minded-man, followed by accounts of his catering to greedy billionaires -- pay-to-play, imitating the worst of RICHARD MILHOUS NIXON, RAY BLANTON and DONALD JOHN TRUMP.

Luke 16:10

The person who is trustworthy in very small matters is also trustworthy in great ones; and the person who is dishonest in very small matters is also dishonest in great ones.

James 1:8

He is a double-minded man, unstable in all he undertakes.

Matthew 6:24

"No one can serve two masters; for either he will hate the one and love the other, or he will be devoted to one and despise the other You cannot serve God and wealth.

Luke 16:13

"No servant can serve two masters; for either he will hate the one and love the other, or else he will be devoted to one and despise the other You cannot serve God and wealth."

1 Corinthians 10:21

You cannot drink the cup of the Lord and the cup of demons; you cannot partake of the table of the Lord and the table of demons.

DeSantis’ nonstop fundraising shows cash, appointments linked

Posted Sep 15, 2019 at 5:28 AM

Sarasota Herald-Tribune

Top donors land posts as governor quietly bolsters his war chest

TALLAHASSEE — Proud of his nonstop approach to leading Florida, Gov. Ron DeSantis also hasn’t taken much of a break from fundraising — quietly salting away almost $2.6 million in contributions since being sworn into office in January.

Unlike his predecessor, now-U.S. Sen. Rick Scott, DeSantis is far from a multi-millionaire who can help underwrite the cost of his own elections. But like Scott, DeSantis also is favoring some of those who give to his political spending committee by handing them appointments to influential government posts.

One of DeSantis’ most reliable donors, Jacksonville developer John Rood, a former ambassador to the Bahamas, recently emerged as a leader of the state’s efforts to help that nation recover from the destruction caused by Hurricane Dorian.

“John knows all the people over in the Bahamas,” DeSantis said Tuesday of Rood, whom he called “a friend of mine.”

Rood and his Vestcor Companies have contributed more than $68,000 to Friends of Ron DeSantis this year, most of it coming this summer as the governor stepped up his fundraising.

Rood, a longtime Republican fundraiser who initially favored DeSantis’ opponent, Adam Putnam, in the Republican primary for governor, faces a tough task in the Bahamas, where he served as ambassador under former President George W. Bush.

Rood said he is working with the organization Mission of Hope International to build 1,000 units of transitional housing in Marsh Harbour, and is looking to raise money from individuals and companies in Florida.

Other DeSantis donors have given, then gotten what look like less demanding assignments.

John Palmer Clarkson, a manufacturing executive, was reappointed to the Jacksonville Port Authority in August, two months after he gave $10,000 to DeSantis’ committee. Charles Lydecker, an insurance executive from Ormond Beach, was named to the State University System Board of Governors in June, after giving $10,000 to DeSantis’ political committee before his election.

Similarly, Stephen Hudson of Fort Lauderdale was appointed by the governor in July to the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. His Hudson Capital Group gave $25,000 last fall to DeSantis.

Ron Howse, president of a Cocoa engineering and land planning company, was reappointed in August to the St. Johns Water Management District, after contributing more than $14,700 last year.

Howse also is chair of the Florida Transportation Commission, and last year helped DeSantis’ campaign by making his airplane available to the governor.

None of the contributors contacted by GateHouse Media returned phone calls. The governor’s office also did not respond to email requesting comment on DeSantis’ fundraising.

DeSantis’ aggressive fundraising recently drew more attention when the Tampa Bay Times reported the existence of internal memos prepared by campaign strategists for the governor that contained different levels of contributions individuals were expected to make in order to meet, golf or dine with the governor.

The documents raised concerns that access to the governor came with a price, and only those with the cash to contribute to his campaign would be heard. DeSantis’ team said they never implemented the pricing scheme.

While DeSantis and Scott have different styles as governors, both are vigorous fundraisers who appear to have embraced a connection between donors and those who serve on state boards and commissions. DeSantis also has followed Scott’s lead of staying in almost constant motion around the state, promoting his policies and programs.

Early in last year’s U.S. Senate campaign, GateHouse newspapers reported that Scott had collected close to $1.4 million from 127 of the people he appointed to boards and commissions, or from their spouses and children. They gave either to his Senate campaign or the New Republican PAC supporting his bid to unseat three-term Democratic U.S. Sen. Bill Nelson.

Such cash, though, amounted only to a drop in the bucket for Scott’s campaign, which spent $82.8 million, including $65 million from the candidate’s own pocket. Scott and his, wife, Ann, are worth at least $352 million, according to U.S. Senate financial disclosures filed last month.

But DeSantis and his wife, Casey, don’t have that kind of bank account.

DeSantis’ financial disclosure filed with the state in July reported a net worth last year of $283,605.

Still, the two Republican leaders share a kinship among donors.

James “Bill” Heavener, whose business interests include serving as CEO of Full Sail University, the Winter Park for-profit college, last month added $50,000 to DeSantis’ political committee, on top of the $150,000 he contributed last year.

Heavener and his wife, Christie, poured at least $228,600 into Scott’s campaign last year. A University of Florida graduate, Heavener was put on the school’s board of trustees by Scott, who also named him to the board of Enterprise Florida, the state’s business development arm.

Danny Doyle Jr., a former Scott appointee to the State University System Board of Governors who runs a Tampa-based imaging company, was part of a family investment of at least $108,600 to the Scott campaign. Last month, he put $100,000 into DeSantis’s account.

Some advisers say the governor’s smart to keep his fundraising machine going well in advance of an expected 2022 re-election campaign. DeSantis and his political committee raised more than $58 million for last year’s governor’s race — a figure his Democratic opponent, Andrew Gillum, came close to matching.

Outside groups put millions more into the race.

“The governor’s race cost $100 million, and it’s hard to raise $100 million in a short amount of time,” said Brian Ballard, a Tallahassee lobbyist who chaired the governor’s inaugural committee.

“It’s smart to start early and do it in a methodical way. It’s not fun for anyone. No one takes joy in fundraising, but he’s smart doing what he’s doing,” Ballard added.

Ballard gave DeSantis’ political committee $10,000 last September. One of his company’s partners, Katherine San Pedro, was named by DeSantis to the Enterprise Florida board in July.

Steve Schale, a Democratic consultant, said that Scott “rewrote the rules for fundraising,” relying on his own political spending committee and shunning the state’s Republican Party.

But when it comes to DeSantis’ attention to fundraising, Schale said it’s no surprise.

“Am I shocked he’s raising money? Hardly. It’s like there’s gambling in ‘Casablanca,’” said Schale, referring to the movie classic.

Like Scott, DeSantis also seems to be going his own way, although Florida GOP chair Sen. Joe Gruters of Sarasota said he has no problem with the governor’s approach.

“The governor and the party are 100% together,” Gruters said. “I couldn’t be happier with his performance, governing. I am his chairman, and he’s doing a great job for the party.”

The donations to Friends of Ron DeSantis also don’t guarantee favorable treatment.

Rood, the prominent donor, is in the housing business. In June, he was stung when DeSantis vetoed $8 million for a Jacksonville workforce housing apartment complex being developed by Rood’s Vestcor Cos.

It was the single biggest line-item veto handed down by DeSantis. And it came after Vestcor gave $25,000 to DeSantis’s political committee four months earlier.

But the development, called Lofts at Cathedral, was seen as the first time state affordable housing money had been earmarked for a specific project.

“I don’t know if that’s the precedent we want to go down,” DeSantis said in explaining why he axed the dollars.

But that evidently didn’t rattle the Rood-DeSantis relationship.

Two months after the veto, records show Vestcor tucked another $18,000 into the Friends of Ron DeSantis account.