Thanks to Vanderbilt University Prof. Matthew Schrag, M.D. for uncovering possible scientific research fraud concerning research on Alzheimer's disease. An investigation is required. Large sums are being spent on research for possible cures. We must get this one right.

From today's issue of SCIENCE Magazine, world's largest scientific journal, published by the American Association for the Advancement of Science:

Blots on a field?IN SECTION FEATURE

In August 2021, Matthew Schrag, a neuroscientist and physician at Vanderbilt University, got a call that would plunge him into a maelstrom of possible scientific misconduct. A colleague wanted to connect him with an attorney investigating an experimental drug for Alzheimer’s disease called Simufilam. The drug’s developer, Cassava Sciences, claimed it improved cognition, partly by repairing a protein that can block sticky brain deposits of the protein amyloid beta (Aβ), a hallmark of Alzheimer’s. The attorney’s clients—two prominent neuroscientists who are also short sellers who profit if the company’s stock falls—believed some research related to Simufilam may have been “fraudulent,” according to a petition later filed on their behalf with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Schrag, 37, a softspoken, nonchalantly rumpled junior professor, had already gained some notoriety by publicly criticizing the controversial FDA approval of the anti-Ab drug Aduhelm. His own research also contradicted some of Cassava’s claims. He feared volunteers in ongoing Simufilam trials faced risks of side effects with no chance of benefit.

So he applied his technical and medical knowledge to interrogate published images about the drug and its underlying science—for which the attorney paid him $18,000. He identified apparently altered or duplicated images in dozens of journal articles. The attorney reported many of the discoveries in the FDA petition, and Schrag sent all of them to the National Institutes of Health (NIH), which had invested tens of millions of dollars in the work. (Cassava denies any misconduct [see sidebar, p. 363].)

But Schrag’s sleuthing drew him into a different episode of possible misconduct, leading to findings that threaten one of the most cited Alzheimer’s studies of this century and numerous related experiments.

The first author of that influential study, published in Nature in 2006, was an ascending neuroscientist: Sylvain Lesné of the University of Minnesota (UMN), Twin Cities. His work underpins a key element of the dominant yet controversial amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s, which holds that Aβ clumps, known as plaques, in brain tissue are a primary cause of the devastating illness, which afflicts tens of millions globally. In what looked like a smoking gun for the theory and a lead to possible therapies, Lesné and his colleagues discovered an Aβ subtype and seemed to prove it caused dementia in rats. If Schrag’s doubts are correct, Lesné’s findings were an elaborate mirage.

Schrag, who had not publicly revealed his role as a whistleblower until this article, avoids the word “fraud” in his critiques of Lesné’s work and the Cassava-related studies and does not claim to have proved misconduct. That would require access to original, complete, unpublished images and in some cases raw numerical data. “I focus on what we can see in the published images, and describe them as red flags, not final conclusions,” he says. “The data should speak for itself.”

A 6-month investigation by Science provided strong support for Schrag’s suspicions and raised questions about Lesné’s research. A leading independent image analyst and several top Alzheimer’s researchers—including George Perry of the University of Texas, San Antonio, and John Forsayeth of the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF)—reviewed most of Schrag’s findings at Science’s request. They concurred with his overall conclusions, which cast doubt on hundreds of images, including more than 70 in Lesné’s papers. Some look like “shockingly blatant” examples of image tampering, says Donna Wilcock, an Alzheimer’s expert at the University of Kentucky.

The authors “appeared to have composed figures by piecing together parts of photos from different experiments,” says Elisabeth Bik, a molecular biologist and well-known forensic image consultant. “The obtained experimental results might not have been the desired results, and that data might have been changed to … better fit a hypothesis.”

Early this year, Schrag raised his doubts with NIH and journals including Nature; two, including Nature last week, have published expressions of concern about papers by Lesné. Schrag’s work, done independently of Vanderbilt and its medical center, implies millions of federal dollars may have been misspent on the research—and much more on related efforts. Some Alzheimer’s experts now suspect Lesné’s studies have misdirected Alzheimer’s research for 16 years.

“The immediate, obvious damage is wasted NIH funding and wasted thinking in the field because people are using these results as a starting point for their own experiments,” says Stanford University neuroscientist Thomas Südhof, a Nobel laureate and expert on Alzheimer’s and related conditions.

Lesné did not respond to requests for comment. A UMN spokesperson says the university is reviewing complaints about his work.

To Schrag, the two disputed threads of Aβ research raise far-reaching questions about scientific integrity in the struggle to understand and cure Alzheimer’s. Some adherents of the amyloid hypothesis are too uncritical of work that seems to support it, he says. “Even if misconduct is rare, false ideas inserted into key nodes in our body of scientific knowledge can warp our understanding.”

IN HIS MODEST OFFICE, steps away from a buzzing refrigerator, Schrag displays an antique microscope—an homage to predecessors who applied painstaking bench science to medicine’s endless enigmas. A small sign on his desk reads, “Everything is figureoutable.”

So far, Alzheimer’s has been an exception. But Schrag’s background has left him comfortable with the field’s contradictions. His father hails from a family of Mennonites, known for their philosophy of peacemaking—but joined the military. The family moved from Arizona to Germany to England before settling in Davenport, a tiny cow town in eastern Washington. After leaving the Air Force, Schrag’s dad became a nurse and worked in a nursing home. As a young teen, Schrag volunteered to visit dementia patients there. “I remembered being mystified by a lot of the strange behaviors,” he says. It was a formative experience “to see people struggling with such unfair symptoms.”

Home-schooled by his mom, Schrag entered community college at 16, like many of the town’s studious kids—including his teenage sweetheart and future wife, Sarah. They now live on a small ranch outside Nashville with their two young children and three aging horses that Sarah grew up with.

While prepping for medical school at the University of North Dakota, Schrag spent long hours in a neuro pharmacology lab absorbing the patient rhythms of science. He repeated experiments over and over, refining his skills. These included a protein identification method known as the Western blot. It uses electricity to drive protein-rich tissue samples through a gel that acts like a sieve to separate the molecules by size. Distinct proteins, tagged and illuminated by fluorescent antibodies, appear as stacked bands.

In 2006, Schrag’s first publication examined how feeding a high-cholesterol diet to rabbits seemed to increase Aβ plaques and iron deposits in one part of their brains. Not long afterward, when he was an M.D.-Ph.D. student at Loma Linda University, another research group found support for a link between Alzheimer’s and iron metabolism. Encouraged, Schrag poured his energy into trying to confirm the connection in people—and failed. The experience introduced him to a disquieting element of Alzheimer’s research. With this enigmatic, complex disease, even careful experiments done in good faith can fail to replicate, leading to dead ends and unexpected setbacks.

One of its biggest mysteries is also its most distinctive feature: the plaques and other protein deposits that German pathologist Alois Alzheimer first saw in 1906 in the brain of a deceased dementia patient. In 1984, Aβ was identified as the main component of the plaques. And in 1991, researchers traced family-linked Alzheimer’s to mutations in the gene for a precursor protein from which amyloid derives. To many scientists, it seemed clear that Aβ buildup sets off a cascade of damage and dysfunction in neurons, causing dementia. Stopping amyloid deposits became the most plausible therapeutic strategy.

Hundreds of clinical trials of amyloid-targeted therapies have yielded few glimmers of promise, however; only the underwhelming Aduhelm has gained FDA approval. Yet Aβ still dominates research and drug development. NIH spent about $1.6 billion on projects that mention amyloids in this fiscal year, about half its overall Alzheimer’s funding. Scientists who advance other potential Alzheimer’s causes, such as immune dysfunction or inflammation, complain they have been sidelined by the “amyloid mafia.” Forsayeth says the amyloid hypothesis became “the scientific equivalent of the Ptolemaic model of the Solar System,” in which the Sun and planets rotate around Earth.

By 2006, the centenary of Alois Alzheimer’s epic discovery, a growing cadre of skeptics wondered aloud whether the field needed a reset. Then, a breathtaking Nature paper entered the breach.

It emerged from the lab of UMN physician and neuroscientist Karen Ashe, who had already made a remarkable series of discoveries. As a medical resident at UCSF, she contributed to Nobel laureate Stanley Prusiner’s pioneering work on prions—infectious proteins that cause rare neurological disorders. In the mid-1990s, she created a transgenic mouse that churns out human Ab, which forms plaques in the animal’s brain. The mouse also shows dementia-like symptoms. It became a favored Alzheimer’s model.

By the early 2000s, “toxic oligomers,” subtypes of Aβ that dissolve in some bodily fluids, had gained currency as a likely chief culprit for Alzheimer’s—potentially more pathogenic than the insoluble plaques. Amyloid oligomers had been linked to impaired communication between neurons in vitro and in animals, and autopsies have shown higher levels of the oligomers in people with Alzheimer’s than in cognitively sound individuals. But no one had proved that any one of the many known oligomers directly caused cognitive decline.

In the brains of Ashe’s transgenic mice, the UMN team discovered a previously unknown oligomer species, dubbed Ab∗56 (pronounced “amyloid beta star 56”) after its relatively heavy molecular weight compared with other oligomers. The group isolated Ab∗56 and injected it into young rats. The rats’ capacity to recall simple, previously learned information—such as the location of a hidden platform in a maze—plummeted. The 2006 paper’s first author, sometimes credited as the discoverer of Ab∗56, was Lesné, a young scientist Ashe had hired straight out of a Ph.D. program at the University of Caen Normandy in France.

Ashe touted Ab∗56 on her website as “the first substance ever identified in brain tissue in Alzheimer’s research that has been shown to cause memory impairment.” An accompanying editorial in Nature called Ab∗56 “a star suspect” in Alzheimer’s. Alzforum, a widely read online hub for the field, titled its coverage, “Ab Star is Born?” Less than 2 weeks after the paper was published, Ashe won the prestigious Potamkin Prize for neuroscience, partly for work leading to Ab∗56.

The Nature paper has been cited in about 2300 scholarly articles—more than all but four other Alzheimer’s basic research reports published since 2006, according to the Web of Science database. Since then, annual NIH support for studies labeled “amyloid, oligomer, and Alzheimer’s” has risen from near zero to $287 million in 2021. Lesné and Ashe helped spark that explosion, experts say.

The paper provided an “important boost”; to the amyloid and toxic oligomer hypotheses when they faced rising doubts, Südhof says. “Proponents loved it, because it seemed to be an independent validation of what they have been proposing for a long time.”

“That was a really big finding that kind of turned the field on its head,” partly because of Ashe’s impeccable imprimatur, Wilcock says. “It drove a lot of other investigators to … go looking for these [heavier] oligomer species.”

As Ashe’s star burned more brightly, Lesné’s rose. He joined UMN with his own NIH-funded lab in 2009. Ab∗56 remained a primary research focus. Megan Larson, who worked as a junior scientist for Lesné and is now a product manager at Bio-Techne, a biosciences supply company, calls him passionate, hardworking, and charismatic. She and others in the lab often ran experiments and produced Western blots, Larson says, but in their papers together, Lesné prepared all the images for publication.

He became a leader of UMN’s neuroscience graduate program in 2020, and in May 2021, 4 months after Schrag delivered his concerns to NIH, Lesné received a coveted R01 grant from the agency, with up to 5 years of support. The NIH program officer for the grant, Austin Yang—a co-author on the 2006 Naturepaper—declined to comment.

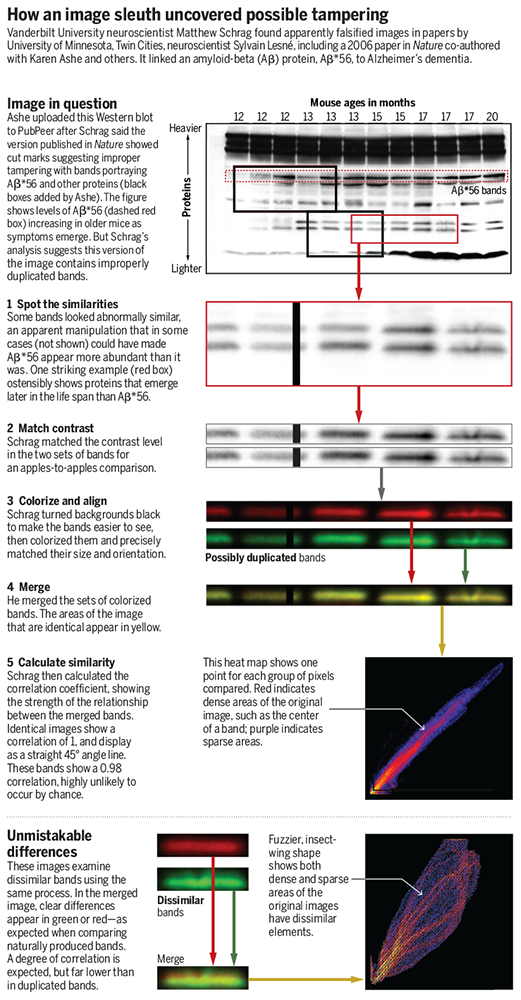

IN DECEMBER 2021, Schrag visited PubPeer, a website where scientists flag possible errors in published papers. Many of the site’s posts come from technical gumshoes who deconstruct Western blots for telltale marks indicating that bands representing proteins could have been removed or inserted where they don’t belong. Such manipulations can falsely suggest a protein is present—or alter the levels at which a detected protein is apparently found. Schrag, still focused on Cassava-linked scientists, was looking for examples that could refine his own sleuthing.

In a PubPeer search for “Alzheimer’s,” postings about articles in The Journal of Neuro-science caught Schrag’s eye. They questioned the authenticity of blots used to differentiate Aβ and similar proteins in mouse brain tissue. Several bands seemed to be duplicated. Using software tools, Schrag confirmed the PubPeer comments and found similar problems with other blots in the same articles. He also found some blot backgrounds that seemed to have been improperly duplicated.

Three of the papers listed Lesné, whom Schrag had never heard of, as first or senior author. Schrag quickly found that another Lesné paper had also drawn scrutiny on Pub-Peer, and he broadened his search to Lesné papers that had not been flagged there. The investigation “developed organically,” he says, as other apparent problems emerged.

“So much in our field is not reproducible, so it’s a huge advantage to understand when data streams might not be reliable,” Schrag says. “Some of that’s going to happen reproducing data on the bench. But if it can happen in simpler, faster ways—such as image analysis—it should.” Eventually Schrag ran across the seminal Nature paper, the basis for many others. It, too, seemed to contain multiple doctored images.

Science asked two independent image analysts—Bik and Jana Christopher—to review Schrag’s findings about that paper and others by Lesné. They say some supposed manipulation might be digital artifacts that can occur inadvertently during image processing, a possibility Schrag concedes. But Bik found his conclusions compelling and sound. Christopher concurred about the many duplicated images and some markings suggesting cut-and-pasted Western blots flagged by Schrag. She also identified additional dubious blots and backgrounds he had missed.

In the 16 years following the landmark paper, Lesné and Ashe—separately or jointly—published many articles on their stellar oligomer. Yet only a handful of other groups have reported detecting Ab∗56.

Citing the ongoing UMN review of Lesné’s work, Ashe declined via email to be interviewed or to answer written questions posed by Science, which she called “sobering.” But she wrote, “I still have faith in Ab∗56,” noting her ongoing work studying the structure of Aβ oligomers. “We have promising initial results. I remain excited about this work, and believe it has the potential to explain why Aβ therapies may yet work despite recent failures targeting amyloid plaques.”

But even before Schrag’s investigation, the spotty evidence that Ab∗56 plays a role in Alzheimer’s had raised eyebrows. Wilcock has long doubted studies that claim to use “purified” Aβ∗56. Such oligomers are notoriously unstable, converting to other oligomer types spontaneously. Multiple types can be present in a sample even after purification efforts, making it hard to say any cognitive effects are due to Aβ∗56 alone, she notes—assuming it exists. In fact, Wilcock and others say, several labs have tried and failed to find Aβ∗56, although few have published those findings. Journals are often uninterested in negative results, and researchers can be reluctant to contradict a famous investigator.

An exception was Harvard University’s Dennis Selkoe, a leading advocate of the amyloid and toxic oligomer hypotheses, who has cited the Nature paper at least 13 times. In two 2008 papers, Selkoe said he could not find Aβ∗56 in human fluids or tissues.

Selkoe examined Schrag’s dossier on Lesné’s papers at Science’s request, and says he finds it credible and well supported. He did not see manipulation in every suspect image, but says, “There are certainly at least 12 or 15 images where I would agree that there is no other explanation” than manipulation. One—an image in the Nature paper displaying purified Aβ∗56—shows “very worrisome” signs of tampering, Selkoe says. The same image reappeared in a different paper, co-authored by Lesné and Ashe, 5 years later. Many other images in Lesné’s papers might be improper—more than enough to challenge the body of work, Selkoe adds.

A few of Lesné’s questioned papers describe a technique he developed to measure Aβ oligomers separately in brain cells, spaces outside the cells, and cell membranes. Selkoe recalls Ashe talking about her “brilliant postdoctoral fellow” who devised it. He was skeptical of Lesné’s claim that oligomers could be analyzed separately inside and outside cells in a mixture of soluble material from frozen or processed brain tissue. “All of us who heard about that knew in a moment that it made no biochemical sense. If it did, we’d all be using a method like that,” Selkoe says. The Nature paper depended on that method.

Selkoe himself co-authored a 2006 paper with Lesné in the Annals of Neurology. They sought to neutralize the effects of toxic oligomers, although not Aβ∗56. The paper includes an image that Schrag, Bik, and Christopher agree was reprinted as if original in two subsequent Lesné articles. Selkoe calls that “highly egregious.”

Given those findings, the scarcity of independent confirmation of the Aβ∗56 claims seems telling, Selkoe says. “In science, once you publish your data, if it’s not readily replicated, then there is real concern that it’s not correct or true. There’s precious little clearcut evidence that Aβ∗56 exists, or if it exists, correlates in a reproducible fashion with features of Alzheimer’s—even in animal models.”

IN ALL, SCHRAG OR BIK identified more than 20 suspect Lesné papers; 10 concerned Aβ∗56. Schrag contacted several of the journals starting early this year, and Lesné and his collaborators recently published two corrections. One for a 2012 paper in The Journal of Neuroscience replaced several images Schrag had flagged as problematic, writing that the earlier versions had been “processed inappropriately.” But Schrag says even the corrected images show numerous signs of improper changes in bands, and in one case, complete replacement of a blot.

A 2013 Brain paper in which Schrag had flagged multiple images was also extensively corrected in May. Lesné and Ashe were the first and senior authors, respectively, of the study, which showed “negligible” levels of Aβ∗56 in children and young adults, more when people reached their 40s, and steadily increasing levels after that. It concluded that Aβ∗56 “may play a pathogenic role very early in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease.” The authors said the correction had no bearing on the study’s findings.

Schrag isn’t convinced. Among other problems, one corrected blot shows multiple bands that appear to have been added or removed artificially, he says.

Selkoe calls the apparently falsified corrections “shocking,” particularly in light of Ashe’s pride in the 2006 Nature paper. “I don’t see how she would not hyperscrutinize anything that subsequently related to Aβ∗56,” he says.

After Science contacted Ashe, she separately posted to PubPeer a defense of some images Schrag had challenged in the Nature paper. She supplied portions of a few original, unpublished versions that do not show the apparent digital cut marks Schrag had detected in the published images. That suggests the markings were harmless digital artifacts. Yet the original images reveal something that Schrag and Selkoe find even more incriminating: unequivocal evidence that, despite the lack of obvious cut marks, multiple bands were copied and pasted from adjacent areas (see graphic, p. 361).

Schrag could find no innocent explanation for a 2-decade litany of oddities. In experiment after experiment using Western blots, microscopy, and other techniques, serious anomalies emerged. But he notes that he has not examined the original, uncropped, highresolution images. Authors sometimes share those with researchers conducting similar work, although they usually ignore such requests, according to recent studies of datasharing practices. Sharing agreements do not include access for independent misconduct detectives. Lesné and Ashe did not respond to a Science request for those images.

Questions about Lesné’s work are not new. Cell biologist Denis Vivien, a senior scientist at Caen, co-authored five Lesné papers flagged by Schrag or Bik. Vivien defends the validity of those articles, but says he had reason to be wary of Lesné.

Toward the end of Lesné’s time in France, Vivien says they worked together on a paper for Nature Neuroscience involving Aβ. During final revisions, he saw immunos-taining images—in which antibodies detect proteins in tissue samples—that Lesné had provided. They looked dubious to Vivien, and he asked other students to replicate the findings. Their efforts failed. Vivien says he confronted Lesné, who denied wrongdoing. Although Vivien lacked “irrefutable proof” of misconduct, he withdrew the paper before publication “to preserve my scientific integrity,” and broke off all contact with Lesné, he says. “We are never safe from a student who would like to deceive us and we must remain vigilant.”

Schrag spot checked papers by Vivien or Ashe without Lesné. He found no anomalies—suggesting Vivien and Ashe were innocent of misconduct.

Yet senior scientists must balance the trust essential to fostering a protégé’s independence with prudent verification, Wilcock says. If you sign off on images time after time, claim credit, speak publicly, and win awards for the work—as Ashe has done—you have to be sure it’s right, she adds.

“Ashe obviously failed in that very serious duty” to ask tough questions and ensure the data’s accuracy, Forsayeth says. “It was a major ethical lapse.”

IN HIS WHISTLEBLOWER REPORT to NIH about Lesné’s research, Schrag made its scope and stakes clear: “[This] dossier is a fraction of the anomalies easily visible on review of the publicly accessible data,” he wrote. The suspect work “not only represents a substantial investment in [NIH] research support, but has been cited … thousands of times and thus has the potential to mislead an entire field of research.”

The agency’s reply, which Schrag shared with Science, noted that complaints deemed credible will go to the Department of Health and Human Services Office of Research Integrity (ORI) for review. That agency could then instruct grantee universities to investigate prior to a final ORI review, a process that can take years and remains confidential absent an official misconduct finding. To Science, NIH said it takes research misconduct seriously, but otherwise declined to comment.

In the fanfare around the Lesné-Ashe work, some Alzheimer’s experts see a failure of skepticism, including by journals that published the work. After Schrag contacted Nature, Science Signaling, and five other journals about 13 papers co-authored by Lesné, a few are under investigation, according to emails he received from editors.

“There are very strong, legitimate questions,” John Foley, editor of Science Signaling, later told Science. He says the journal has contacted authors and university officers of two papers from 2016 and 2017 for a response. It also recently issued expressions of concern about the articles.

A spokesperson for Nature, which publishes image integrity standards, says the journal takes concerns raised about its papers seriously, but otherwise had no comment. Days after an inquiry from Science, Nature published a note saying it was investigating Lesné’s 2006 paper and advising caution about its results.

The Journal of Neuroscience stands out with five suspect Lesné papers. A journal spokesperson said it follows guidelines from the Committee on Publication Ethics to assess concerns, but otherwise had no comment.

“Journals and granting institutions don’t know how to deal with image manipulation,” Forsayeth says. “They’re not subjecting images to sophisticated analysis, even though those tools are very widely available. It’s not some magic skill. It’s their job to do the gatekeeping.”

Holden Thorp, editor-in-chief of the Science journals, said the journals have subjected images to increasing scrutiny, adding that “2017 would have been [near] the beginning of when more attention was being paid to this—not just for us, but across scientific publishing.” He cited the Materials Design Analysis Reporting framework developed jointly by several publishers to improve data transparency and weed out image manipulation.

As federal agencies, universities, and journals quietly investigate Schrag’s concerns, he decided to try to speed up the process by providing his findings to Science. He knows the move could have personal consequences. By calling out powerful agencies, journals, and scientists, Schrag might jeopardize grants and publications essential to his success.

But he says he felt an urgent need to go public about work that might mislead the field and slow the race to save lives. “You can cheat to get a paper. You can cheat to get a degree. You can cheat to get a grant. You can’t cheat to cure a disease,” he says. “Biology doesn’t care.”

Like other anti-Aβ efforts, toxic oligomer research has spawned no effective therapies. “Many companies have invested millions and millions of dollars, or even billions … to go after soluble Aβ [oligomers]. And that hasn’t worked,” says Daniel Alkon, president of the bioscience company Synaptogenix, who once directed neurologic research at NIH.

Schrag says oligomers might still play role in Alzheimer’s. Following the Naturepaper, other investigators connected combinations of oligomers to cognitive impairment in animals. “The wider story [of oligomers] potentially survives this one problem,” Schrag says. “But it makes you pause and rethink the foundation of the story.”

Selkoe adds that the broader amyloid hypothesis remains viable. “I hope that people will not become faint hearted as a result of what really looks like a very egregious example of malfeasance that’s squarely in the Aβ oligomer field,” he says. But if current phase 3 clinical trials of three drugs targeting amyloid oligomers all fail, he notes, “the Aβ hypothesis is very much under duress.”

Selkoe’s bigger worry, he says, is that the Lesné episode might further undercut public trust in science during a time of increasing skepticism and attacks. But scientists must show they can find and correct rare cases of apparent misconduct, he says. “We need to declare these examples and warn the world.”

With reporting by Meagan Weiland. This story was supported by the ScienceFund for Investigative Reporting.

No comments:

Post a Comment